Not every molecule gets to find their best “partner” in life. Luckily in 2019, Dr. Chris Orvig and his team at the University of British Columbia constructed a partner molecule for Gallium to work with in medical imaging. They also determined that their creation has superior stability and binding ability compared to similar molecules currently being used.

THE NEW MOLECULE IN TOWN

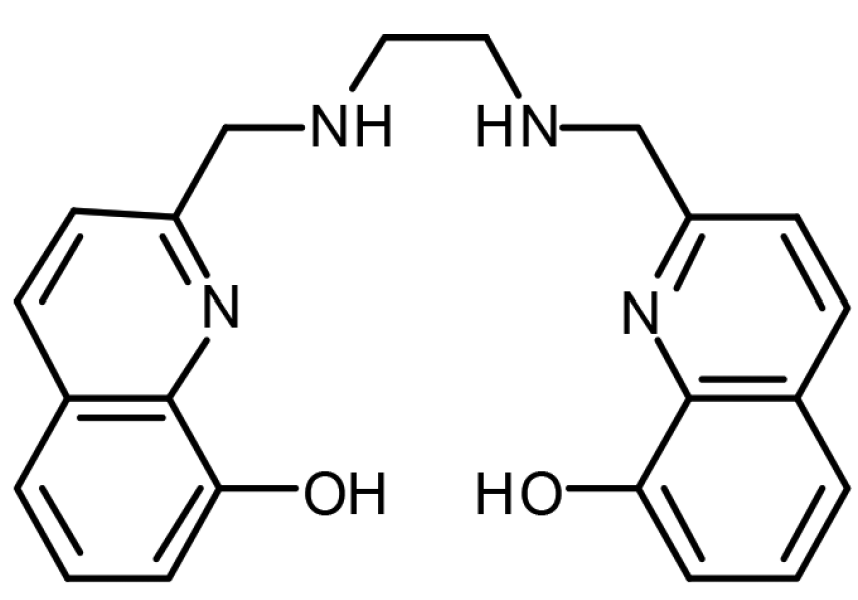

The partner molecule is a chelating ligand known as H2hox. Let’s break down its name piece-by-piece to get a better understanding of what it does.

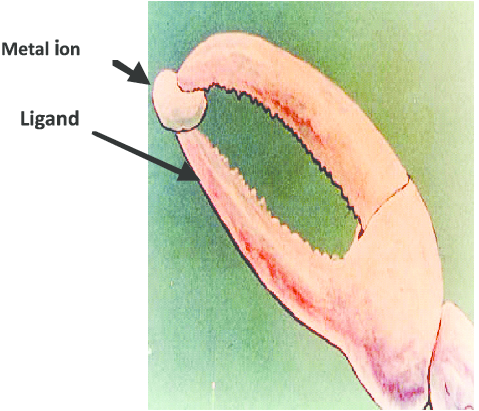

A ligand is a molecule that binds onto a metal ion such as iron (Fe3+) or copper (Cu2+). In the case of H2hox, the metal ion is Gallium (Ga3+ ).

The word chelating comes from the latin root word chela, which means claw. This is because chelating ligands have multiple points of attachment to a metal ion, similar to a crab’s claw, making them significantly stronger binders to metal ions.

- A crab’s claw modelling the function of a chelating ligand.

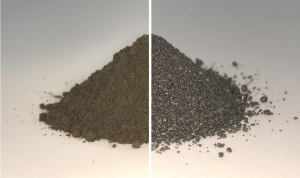

- The pincer-like chemical structure of the chelating ligand H2hox..

Image sources (left to right): Research Gate, Wang et al..

THE DUO GETS TO WORK

H2hox is used in a form of medical imaging known as positron-emission tomography (PET). PET imaging is used to diagnose health issues related to the processes occurring inside our cells, such as cancer.

The main function of H2hox in PET imaging is to bind to radioactive Gallium ions, which aids in producing an image of a desired area or tissue inside the body.

To test how well H2hox worked together with its partner, Gallium, the researchers conducted a PET scan in mice. The group witnessed high stability of the dynamic duo within mice, and they observed that it was rapidly excreted from the mice, which is important for a decrease in side effects.

Furthermore, the ligand has a strong affinity to Gallium, such that only low amounts of ligand are needed to significantly bind to Gallium ions in just five minutes! As a result of the molecule’s advanced properties, H2hox surpasses any ligand currently used as a Gallium’s partner.

ALL IT TAKES IS 1 STEP

In the lab, H2hox is synthesized (made) in only one reaction and is easy to purify, unlike similar ligands which are synthesized over multiple labor- and resource- intensive steps. As a bonus, the chemicals used to make it are inexpensive and readily available.

To put this into perspective, it’s like baking a box cake versus baking a cake from scratch. The former is quite easy to do, while the latter is a lot harder and is more labour-intensive. Ease of manufacturing is a key feature because it determines the commercial success of the product.

THE FUTURE IS PROMISING

The combination of unprecedented properties and easy synthesis makes H2hox a launching-off point for the development of even better chelating ligands to improve the future of PET imaging. With H2hox being such an advantageous molecule for Gallium PET imaging, we cannot wait to see what else this dynamic duo has to offer the world.

Literature cited:

- Wang, X.; Jaraquemada-Pelaez, M. d. G.; Cao, Y.; Pan, J.; Lin, K.-S.; Patrick, B.O., Orvig, C. H2hox: Dual-Channel Oxine-Derived Acyclic Chelating Ligand for 68Ga Radiopharmaceuticals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 58, 2275-2285

-Group 6 (Mark, Akash, Athena, Charles)