When patients are diagnosed with breast cancer, the cancer cells have already metastasized to another part of the body. However, the number of cancer cells involved in this process is negligible, and current equipment cannot detect them. Cancer cells after metastasis remain inactive, which seems unlikely to threaten patients’ health. Nevertheless, those dormant cancer cells are time bombs. One way to set them off, surprisingly, is through cancer surgery.

Recent research led by Dr. Robert Weinberg of the Whitehead Institute found the mechanisms that may explain why surgeries activate the hidden cancer cells. They designed a set of comparison experiments based on mice that injected with breast cancer cells and observed how breast cancer developed in different conditions.

To simulate the postoperative recovery process, scientists implanted sterile sponges in the mice injected with breast cancer cells. This “unnatural” design may be controversial, but it maintains all animals experiencing the same experimental conditions.

“Weinberg gets some pushback because he works on artificial systems, but this is often the only way to expose fundamental principles of biology.” said biologist Sui Huang, professor of the Institute for Systems Biology, who was convinced by this experiment.[1]

Figure 1. (A) Schematic illustrating the experimental design. Mice had been previously wounded by sponge implantation at one or two distant sites. (B) Tumor diameter during the one-month experiment. (C) Tumor incidence as a function of time (n = 9 to 10 per group) for the experimental and control group. Data are plotted as means ± SEM. P values were calculated using the Mann-Whitney test (P < 0.05). Source: Translational Medicine Science

One month after the surgery, researchers tested the number of cancer cells that remained in mice’s bodies. Figure 1 summarizes the results: for those that accepted the surgery, 60% of mice developed tumors in other parts of the body. While in the comparison group, the value is only 15%. Based on the results from 270 mice, Weinberg concluded that surgery could accelerate the cancer cell metastasis and even facilitate tumor formation.

The reason for the effect, as explained in the paper, has to do with the immune system. During the surgical wound recovery process, the inflammatory response restricts the immune system. Therefore, the “guard cells” cannot effectively monitor the cancer cells, resulting in metastasis and tumor formation.

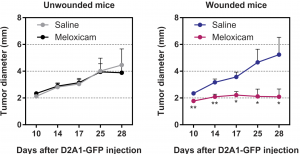

Figure 2. Tumor diameter after the injection of cancer cells into previously unwounded (left) or wounded (right) mice treated with saline or meloxicam (n = 15 mice per group). Data are plotted as means ± SEM. P values were calculated the Mann-Whitney test P < 0.0005. Source: Translational Medicine Science

The good news is common pain killers, such as aspirin, can efficiently inhibit this process. Scientists found that many nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can effectively suppress tumor formation resulting from surgical wounds. Figure 2 shows that the wounded mice had a constant tumor size at around 2mm after given meloxicam, while the comparison developed tumors at average 5mm. Note the experiment only tested meloxicam; aspirin was also proved to be effective in the follow-up research.

Although the results are quite delightful, whether we can apply the same experiment to humans remains unclear. Weinberg pointed out that the aim of the investigation is not telling people not to trust lumpectomy or other tumor surgeries but develop a more effective treatment for postoperative recovery. He hoped that this research would promote further experiment on human and test whether drugs like aspirin has the same effect in the human body.