We are one step closer to achieving communication with those 37.2 trillion tiny cells making up our bodies. Our cells communicate using sugars, and different modifications to these sugars can change the way our cells communicate with each other. Just last year, researchers at the University of British Columbia, led by Dr. Stephen Withers, did exactly this! They designed a unique way to tinker with sugars’ chemical structures by using chemicals found in bacteria. The same bacteria living in our gut.

what exactly are sugars?

No ambiguity here! Chemists work with sugars based off molecules in this sugar cube. Credits: The Verge

To be specific, the type of sugars Wither’s team studied were simple sugars; hexagonal-shaped molecules, often joined to other molecules known as “acceptors”. The problem chemists face is like the average love life. Similar to starting a relationship with someone, joining acceptors to sugars is also quite difficult. Luckily for sugars, Mother Nature has come up with some solutions: enzymes, which are helper molecules that speed up the pairing or unlinking of two molecules.

A SOLUTION UNDER OUR NOSES…

Instead of struggling to find ways of joining sugars and acceptors, Wither’s team thought: Why not hijack Mother Nature and use these enzymes? To make their idea a reality, they extracted sugar-specific enzymes from E. Coli, a type of bacteria that lives inside the human gut. These bacteria manufactured 175 sugar-specific enzymes, and from these they chose eight enzymes that were compatible with the sugars and acceptors they were interested in.

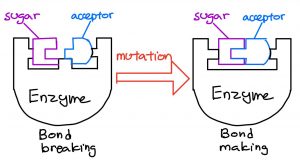

It seemed like Wither’s team now had everything needed to join the desired acceptors to the sugars; however, there was still a problem. The sugar-specific enzymes they got from E. Coli did the exact opposite of what they wanted; instead of forming sugar-acceptor linkages, they were specialized in breaking them. Enzymes that break sugar-acceptor linkages are analogous to using a screwdriver to loosen a screw, while enzymes that form sugar-acceptor linkages are like tightening a screw.

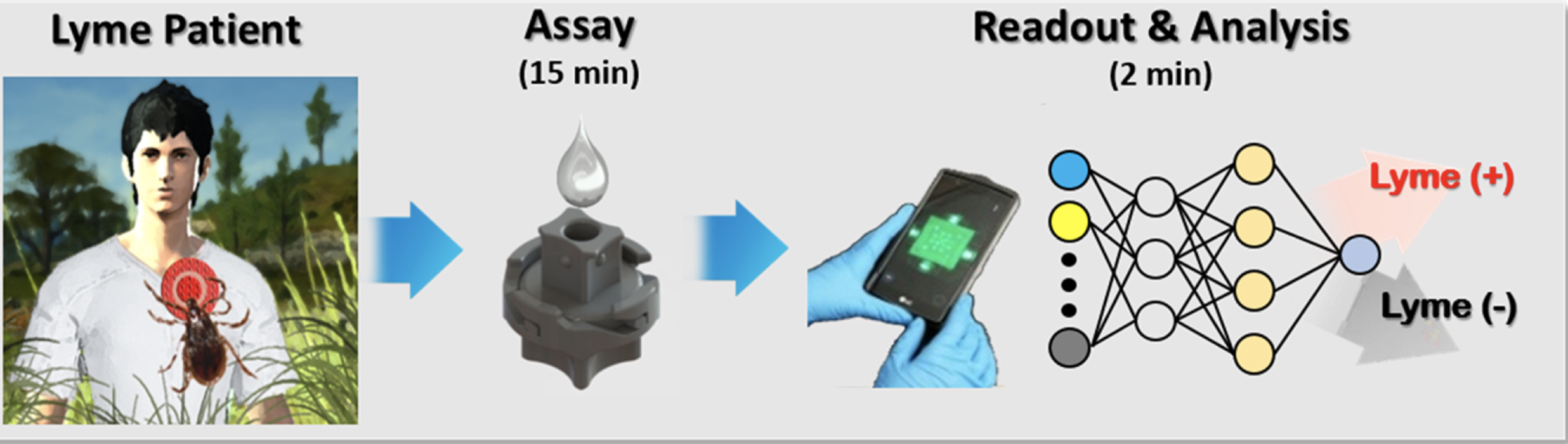

A small modification changes the function of the enzyme. Credits: Blog post authors

To solve this problem, they reverse-engineered the enzymes specialized in breaking linkages into those that form linkages, by changing a small part of the enzymes’ structure, similar to changing the tips on a screwdriver. As a result, Wither’s team now had eight enzymes specialized in forming different sugar-acceptor linkages.

More than just a bond…

Now being able to freely and efficiently modify sugars, there is a big potential for researchers to join in on the conversations with our cells. Why is this important? Often, there is miscommunication within our cells which can lead to serious trouble.

One example is cancer; which is partly caused by cancer cells using abnormal sugar molecules as a form of miscommunication, to avoid being cleared up by immune cells. One potential treatment is a sugar-based vaccine, which tells our immune cells to ignore this miscommunication and target tumor cells.

The challenge of designing a sugar-based vaccine isn’t just relevant to cancer, but other diseases as well which occur also as a result of miscommunication. With Wither’s research, designing these sugar-based drugs won’t be as difficult thanks to their novel way of bonding sugars to other molecules. This research brings us one step closer to talking to our cells, helping with the battle against diseases.

Story source

Armstrong, Z.; Liu, F.; Chen, H.-M.; Hallam, S. J.; Withers, S. G. Systematic Screening of Synthetic Gene-Encoded Enzymes for Synthesis of Modified Glycosides. ACS Catalysis 2019, 9 (4), 3219–3227.

– Kenny Lin, Pricia Ouyang, Tom Hou, Aron Engelhard (CO-10)