Have you ever ended up in the hospital and needed a blood transfusion? Well, that’s about to get a whole lot easier for people everywhere! An article published by Nature Microbiology in June 2019 by Dr. Stephen Withers, studied a new method in converting type A blood to the universal type O blood using bacteria found in the human gut! [1]

A team led by Dr. Stephen Withers at the University of British Columbia has developed a method which would eliminate the need for blood-type compatibility, reducing the risks of blood transfusions.

What are blood types?

There are 8 different blood types, and before these findings, these blood types were not all compatible with each other. Each blood type can only receive from other specific types.

In human bodies, there are 8 types of red blood cells. These types are determined by two factors: Blood Groups and Rh Factors.

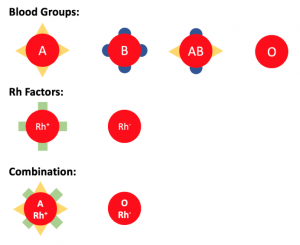

We have 4 different blood groups: A, B, AB and O, different blood groups carry different signals (see Image 1).O-type cells do not carry any signals.

Similarly, Rh-positive red blood cells carry another signal, and Rh-negative cells carry nothing. Blood groups and Rh factors are combined, so that we have blood types such as A positive, O negative, etc.

Image depicting the different signals on red blood cells. Created by Eric Ding using PowerPoint.

If we transfuse O negative cells, which do not carry any signals, they can be recognized by anyone with any type of blood.

However, if we transfuse A positive red blood cells to a patient with AB negative blood, the immune system can recognize the triangle signal, but not the rectangular signal. The body will consider A positive red blood cells as enemies and attack them. This reaction can be fatal.

This problem has existed since blood transfusions were first scientifically achieved, and scientists have been looking for a solution for just as long. It turns out the solution was hiding right under our noses; inside our stomachs, to be specific!

The findings

Inside the human gut are thousands of microscopic bacteria which we use to digest food and convert it into energy. As it turns out, these bacteria are very good at safely interacting with the human body in helpful ways.

The researchers removed these bacteria through human faeces and found they could be used in exactly the way they were hoping. “Why would they be looking in our stomachs for this solution?” you might ask.

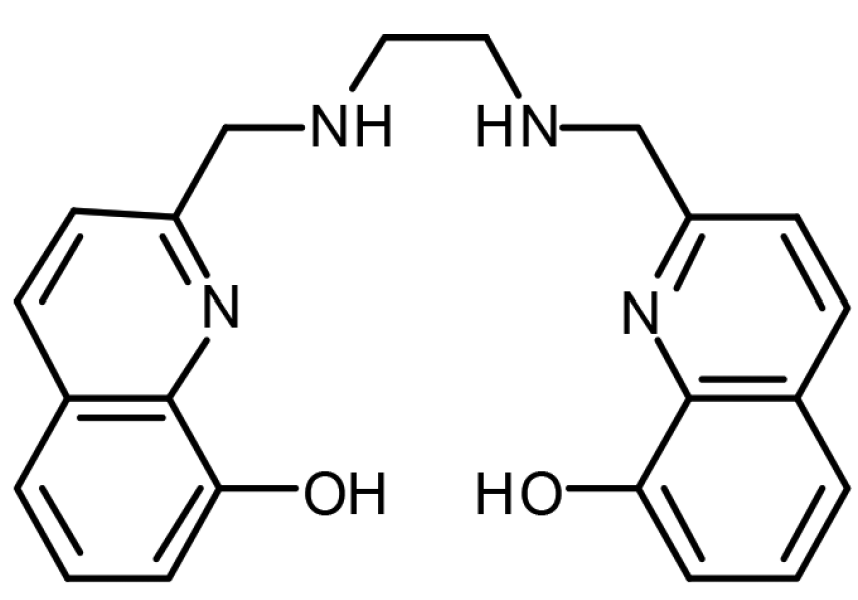

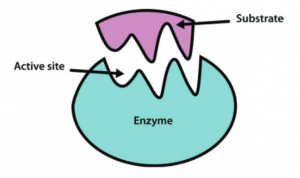

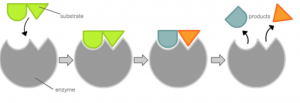

The Withers group were on a hunt for a special kind of protein called an enzyme. Enzymes are produced by the body with a very specific task, and that task varies based on what the body wants it to do.

Since our gut has the ability to process blood and turn it into energy, Withers and his team decided to see if these enzymes could be harnessed for their research. As it turns out, they were completely correct.

An enzyme interacting with a specific molecule (known as the substrate) and cutting it into two different products. Modified from Wikipedia Commons.

The group screened more than 20,000 samples to find two enzymes that were particularly good at cutting the signal on A-type blood leaving us with O-type blood. These were removed from the body and tested on real red blood cells.

The researchers discovered that the enzymes could efficiently cut the specific part of the A-type blood, essentially leaving us with type O red blood cells.

These two types of enzymes were 30 times more efficient than previous methods, which means we only need a tiny amount of these enzymes to convert A, B, and AB types of red blood cells to O type red blood cells.

Impacts

In January 2020, the American Red Cross announced that it has a ‘critical’ shortage of type O blood. In the United States and Canada alone, 4.5 million patients need blood transfusions every year.[2]

This high demand means that oftentimes, the supply cannot meet the demand.

With this new discovery, incompatible blood types can be made compatible. This would increase the supply of compatible blood, which means more people can be helped.

While the process has been completed in the lab, it has yet to be scaled up to convert massive amounts of blood at a time. This may take some time to accomplish.

However, countless people will be helped and countless lives will be saved. And if one thing is for certain, it’s that blood donations will forever be easier.

References

- Rahfeld, P., Sim, L., Moon, H., Constantinescu, I., Morgan-Lang, C., Steven, J. H., Kizhakkedathu, J. N., Withers, S. G.; An enzymatic pathway in the human gut microbiome that converts A to universal O type blood. Nature Microbiology. 2019, 1475-1485.

- Community Blood Bank of Northwest Pennsylvania and Western New York. 56 facts about blood. https://fourhearts.org/facts/ (accessed March 22, 2020)

– Griffin Bare, Eric Ding, Chantell Jansz