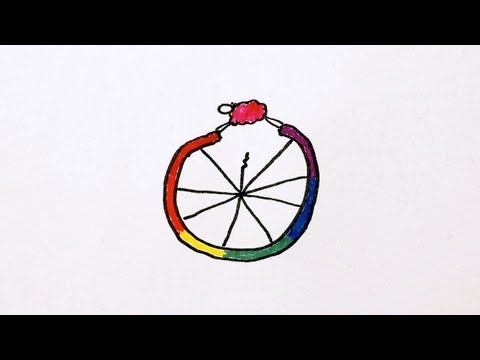

Image courtesy of Darren Hardy

Ever since reading about the concept of a ‘cognitive model’ in Stephen Hawking’s book The Grand Design, I’ve become quite fascinated by the barrier between the world around us and our experience of that world. Therefore, when I first learned that the colour pink (magenta) is actually a construct of our minds and not something that exists in the visible spectrum of light, I began immediately drawing up a blog post in my mind, in much the same way.

Now, you might point out that all of the colours we see are technically constructs of our minds, but the idea here is that the colour magenta, unlike the others, is not based on a naturally occurring wavelength of light. Our experience of all the other colours is based on wavelengths of light between 390-750nm, which is the visible spectrum of light in humans.

The visible portion of the EMS. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Whenever we sense a particular wavelength of light, we have a colour attributed to it. Likewise, whenever we see combinations of wavelengths, we can sum them to identify the resulting wavelength we see – mixing yellow (570–590 nm) and blue (450–495 nm) to get green (495–570 nm) for example. However, when you mix colours from completely opposite ends of the spectrum, what happens? They don’t sum together to make one of the colours in the middle of the spectrum where the greens are found, like you might suspect.

Apparently, our brains have decided that mixing yellow and blue should not give the same result as mixing red and purple, so the colour pink has been created to fill in the gap. Indeed, if you’ve ever wondered what it would look like if your brain created its very own visual cue for something not occurring in nature, then pink is your answer. Here’s a video explaining the concept:

The hues of these two identical dots (created by differences in the surrounding whites) can make one look brown and one orange to us. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Some people might point out that brown isn’t on the colour wheel either, but interestingly enough, it turns out that brown is actually just a shade of oranges, reds or yellows. The proposed explanation is that throughout evolution, we have developed a need to be more sensitive to differences between particular shades of these colours due to dirt, leaves and trees being common experiences for us. So while brown has its own name because it appears differently to us from the other colours in the spectrum, it also has its own wavelengths and shouldn’t really be thought of as a separate colour from the reds, yellows or oranges it belongs to. The biggest difference between pink and brown, as interpretations of the visible spectrum, is that pink doesn’t actually have its own wavelength of light or a position on the visible spectrum of light.

Cameron Tough