Hummingbird, zebra finch, and pigeon. All images sourced from Flickr

The brain is an intricate and complex structure that takes a lifetime to understand completely. You may be slightly familiar with the human brain, but have you ever wondered how the brain of an animal functions? We had the opportunity to interview lead researcher Dr. Andrea Gaede to discuss her groundbreaking bird brain research. The study, based in Vancouver at the University of British Columbia in 2018, was conducted to investigate how bird species process visual motion in their brain and to find out if these processes are dependent on the way the bird species flies. First, they captured the birds, then injected their brains with a fluorescent dye, and finally analyzed the individual brains with imaging software.

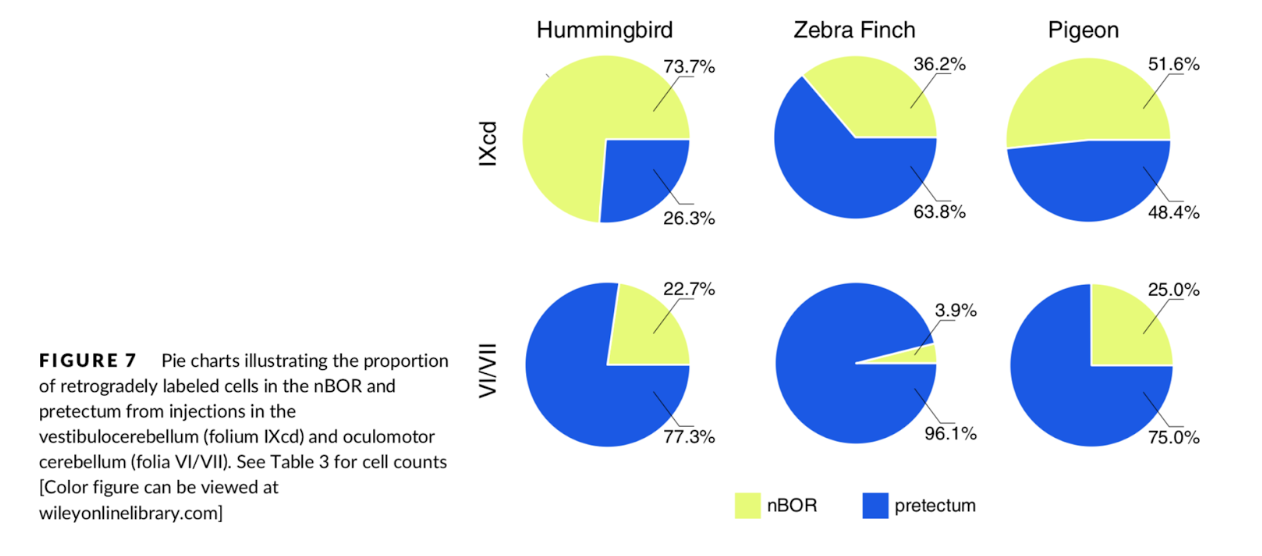

Dr. Gaede’s findings show that bird species with distinct modes of flight will have significantly different ways of processing visual motion within their brain. By using advanced imaging, you can actually see the different visual flow patterns in their brain!

Figure 7 from Dr. Gaede’s paper

The results of Dr. Gaede’s study suggest a relationship between bird size, unique flight behaviours, and the location in the brain that responds to visual stimuli.

In the interview with Dr. Gaede, we were able to learn more about her research study and why she is so interested in the bird brain. From acquiring the birds used in the experiment, to discussing what her findings mean for the future of technology and neuroscience, Dr. Gaede gives us insight into the whole process. For all the details, listen to the podcast below!

Why Hummingbirds: How is the hummingbird brain different from all other brains?

A hummingbird mid-flight. Image sourced from Flickr

Dr. Gaede used hummingbirds, pigeons, and zebra finches in her study, but the main focus of her research was to understand hummingbirds. Special characteristics in the hummingbird brain can be attributed to their unique flight patterns. Hummingbirds have the ability to maneuver rapidly in all directions, in a way no other birds can. They have a physical sensitivity to movements in their surrounding environment. Instinctively, they hover backward when something is approaching, and forwards when they see open space in front of them. Additionally, a portion of their brain, called the LM (lentiformis mesencephali), is enlarged in comparison to the size of their bodies. This enlargement is expected to be a neural specialization for hovering, therefore studying this region is a main focus of Dr. Gaede’s study.

Bird Neuroscience and Human Technology — Why Does It Matter to Us?

Dr. Gaede mentioned in her interview that her research can be used to make advancements in technology for drones and autonomous aerial devices. Machines based on nature and animals rarely disappoint, and this can potentially be the case with a drone based on a hummingbirds’ structure and flight pattern. Hummingbirds have unique modes of flight, and are extremely light, which makes them an ideal model for a drone. Previously, attempts have been made at creating drones similar to hummingbirds; however, they failed. After some time, a breakthrough was made and a drone that is based off of a hummingbird finally took flight, and it did not disappoint!

Watch the video below to see how this innovation was made possible:

Future Research

Dr. Gaede is continuing to research the bird brain, and is currently working on a study about cell stimulation during different activities. The study is conducted by putting an animal through a certain behaviour, for example perching or hovering, and then euthanizing them immediately after. Afterwards, she uses advanced techniques to determine which cells in the brain were used to perform that behaviour. This would help us to further understand how visual information is processed into motor-function output during flight, therefore promoting improvements in the technology of hummingbird drones!

Written by Francine Flores, Eric Hsieh, Alexandra McDonald, and Pawan Uppal