Parker Johnson recently tagged me on Facebook for my opinion on this piece that was published a couple of years ago by a retiring, award-winning teacher in the US. Summary: The move to school accountability via standardized testing is not helping make education stronger and hampers teachers in what they can do.

A thoughtful discussion occurred among Parker’s Facebook friends. This is my side of that conversation:

It’s an interesting op-ed and very much of a piece with everything I’ve read by leading educators out of the US. One book I read suggested that as much as 1/3 to 1/2 of student time was spent writing local, state and national mandatory assessments. Whether that was dramatic license or not, I don’t know, but even if it were half true – 1/6 to 1/4 of the time being spent on mandatory assessments – then it’s still too much.

But, credit where it’s due, the current BC Curriculum revision is being led, in large part, by teachers in the system. The philosophies underpinning the revision are based in the idea that less content and more concepts and analysis should be taught – if anything the critique is now reversed – science and math experts especially are concerned that teachers will struggle to implement the curriculum because it leaves too much to be imagined by teachers themselves and provides no textbooks to support the learning.

In short, this is a classic public policy case study – policy is a blunt instrument and you can’t have everything.

The kind of policies we see in the US appear to be aimed at holding accountable the least successful teachers. Why those teachers are ‘unsuccessful’ is a big question – as is simply coming up with an appropriate definition of success. But in essence the idea is that too much latitude leads to poor results: if only we could tell teachers what to do and incentivize them into doing it, we would have better outcomes. But this comes at the expense of clipping the wings of good teachers. Classic Harrison Bergeron and lowest common denominator thinking.

The BC Curriculum is pitched at the most successful teachers. It gives them latitude and professional autonomy, but this comes at the expense of supporting the teachers least able to imagine their own approach to implementing the curriculum. The ambition of the curriculum model is what is causing a fair degree of anxiety among teachers and I certainly believe that doing it well will require way more work than before for the median teacher.

But, being someone who thrives in creative environments, I’d rather have the autonomy.

The Hidden Dimension: University admissions and pedagogy

Where we will see challenges in terms of University success (and already are seeing challenges) is in terms of the orientation away from using work habits in grading (losing marks for submitting late, for example). The universities’ pedagogy is, mostly, old-school. The K-12 system is new-school and students have an ever-bigger leap as they try to bridge the gap from the K-12 ‘demonstrate your learning how you can and when you can’ approach to a classic ‘the paper is due on Tuesday, late papers lose one letter grade per day’ approach.

Another big challenge is that the K-12 pedagogy is pointing us away from using normed grades, for a variety of reasons, many of which are valid.

The challenge this poses is that it negates the ‘grades as social currency’ function of grades. We currently allocate scarce societal resources (usually educational opportunities) based on grades because they provide a reasonably reliable way to compare students to each other. The question that isn’t being asked in enough places as we move away from normed grades is:

“What replaces grades when we need to allocate scarce social resources like university seats fairly to students based on academic achievement/potential?”

Another interesting feature of moving away from grades (which the new curriculum is doing) is that it isn’t at all clear what replaces them. The reason parents want straight A’s is not so much because it is the most beautiful letter, but because those grades unlock opportunities. This will push universities to create other ways of ranking students, and likely it will make the ranking systems more complex and therefore more opaque.

A ‘transparently gameable’ system like SFU’s admissions to most programs is, more or less, democratically gameable. It takes 3 minutes to explain that better grades = admission. The game is obvious – get better grades. Of course, there is a solid link between your grades and your parents’ income and education, but at least the less-well off don’t need to expend resources to gain insight into how to score goals and have a reasonable chance of maximizing their GPA.

Now, make the system more complex. Maybe you need an essay, perhaps you need to show ‘leadership’, ‘engagement’, ‘excellence’ – all the things that modern research on predicting success at universities suggest we should look for. The game now becomes more difficult to read. Experts exist who can, for a healthy fee, provide the kind of personalized system navigation that public schools simply cannot. They can explain the rules of the game and give you individualized coaching about how to play it so that you run up the score.

Gaming complex selection processes also has a wealth bias. International-level activities typically get far more weight than school level ones. But its easier for a wealthy family to support a child in, say, international gymnastics competition than it is for a poor one. Gymnastics is expensive, and you aren’t participating if your parents can’t afford it. It doesn’t mean that every rich kid will be a competitive gymnast, but it does suggest that the vast majority of internationally competitive <fill in the blank> will not come from low-income families. Repeat this phenomenon across a variety of fields (athletics, academic competitions, music and the arts, etc) and that’s what you call systemic bias.

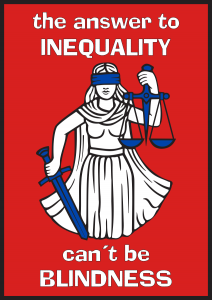

It’s a natural instinct to game a system, so I certainly don’t judge any family that uses their resources to provide the best opportunities for their child. The challenge we have as educators is to be aware of the ways systemic bias creeps in, realize that there is no clear way to stop that (without some form of massive change) and, notwithstanding the seeming futility of it, try in small and subtle ways to foster those we can see with great potential towards opportunities that will help level the playing field somewhat for them and give them the opportunities to shine. Systems are often designed to be blind. Teachers are the eyes of the system and can be the main source of equity-oriented resilience needed in a system that focuses on equality.

Photo Credit: OSeveno (Own work) [CC BY 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons