A carving that is part of our family’s growth chart.

Our task this week was to choose a five letter word and craft stamps for each of the letters in the word to produce two final prints as similar as possible to each other. After watching Danny Cooke’s YouTube video about the letterpress and movable type workshop at the University of Plymouth, I knew that achieving the level of quality I sought would not be easy, but I also knew that I could rely on my experience with wood carving as a guide. The key, I figured, would be to try to emulate the pieces that I saw in terms of their shape and structure, so that they could be positioned repeatedly to achieve the duplicate copies.

I started by ideating words composed of unique alphabetical characters while reflecting on some of the concepts in this week’s readings. One of the ideas that stood out was Marshall McLuhan’s elaboration of J. C. Carothers’s postulations about the senses, and how the advent of literacy (as in the adoption of a visual representation of oral language), impacts the “ratio” between the senses (McLuhan, 2011, p. 24-29). I selected the word “sound”, because I truly appreciate the sense of hearing above all other senses, even though sight is arguably the most valuable.

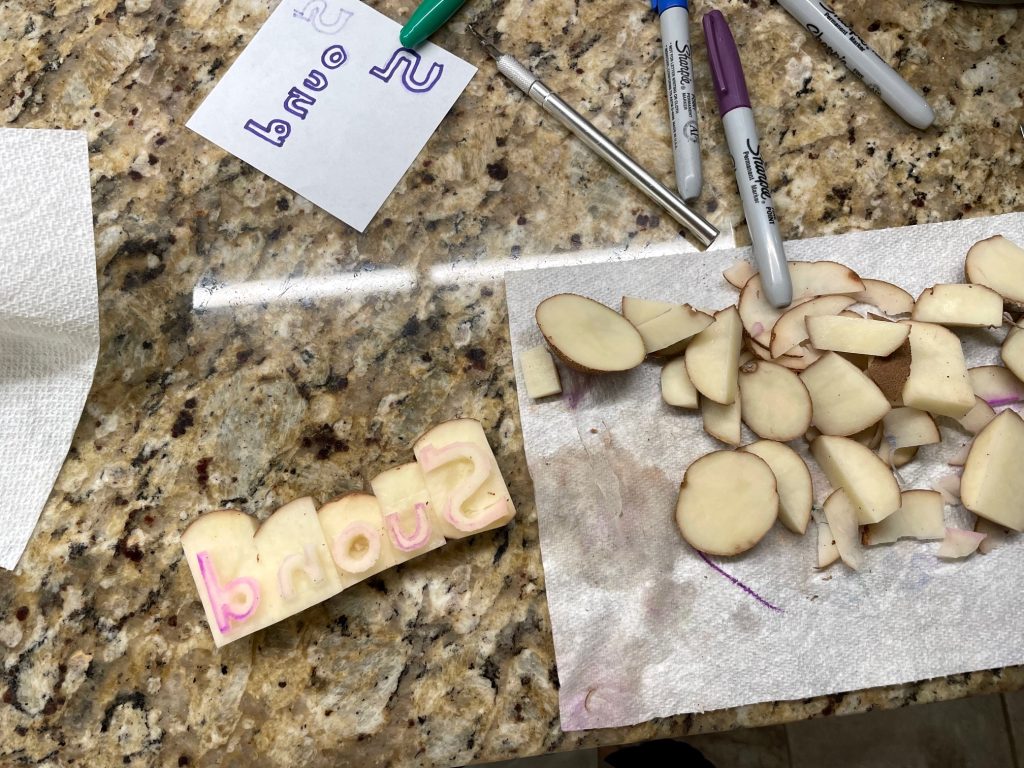

Initial potato stamp preparation and creation

One mental note I had made while watching the video, was the squareness and depth of each of the letters. I surmised that it would be important for each piece to have edges that were proportionally similar so that the spacing and alignment were controlled. I also realized that the letters on the pieces were reflections, so I wrote the characters on a thin piece of paper so that the ink could be seen through to the other side.

After drawing the shapes of the reflections on halved potato pieces, I carefully carved the cut face using an Xacto and a kitchen knife. As I carved, I thought of the perseverance and patience that Gutenberg must have had in developing the system that he did, not to mention the ingenuity and foresight to make the work of copyists more economical. In Empire and Communications, Harold Innis describes industries like metallurgy and paper production – developing adjacent to block printing – as important for setting the stage for the invention of the printing press (Innis, 2007, p. 164), and the clear demand for increased production by ecclesiastics.

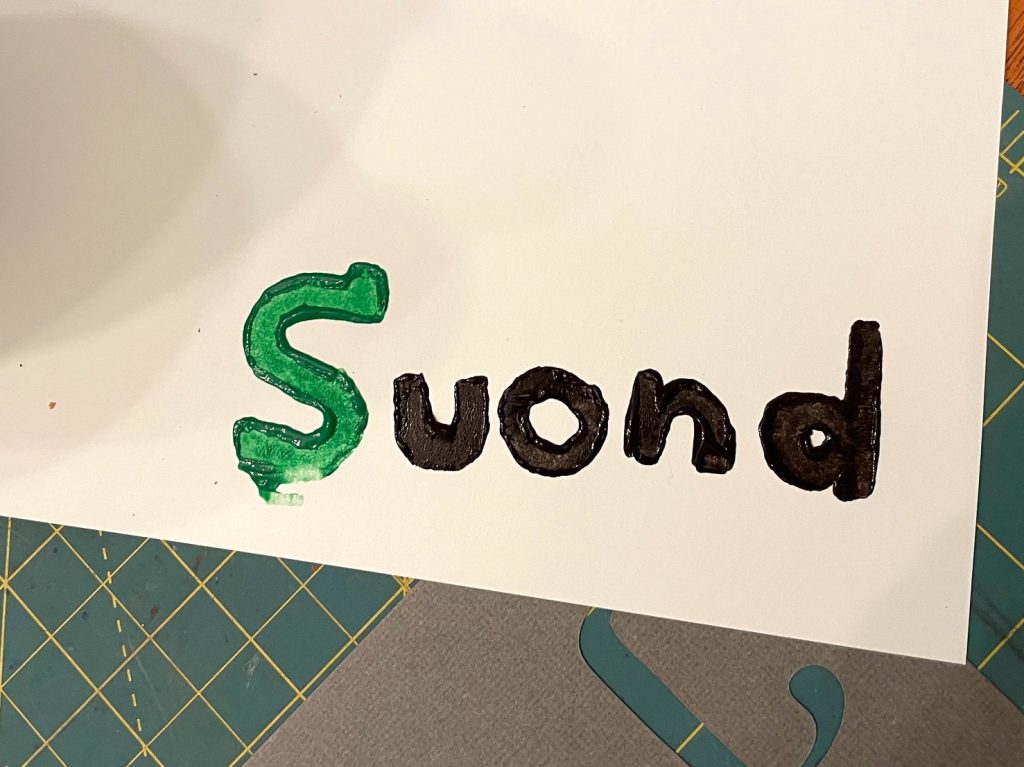

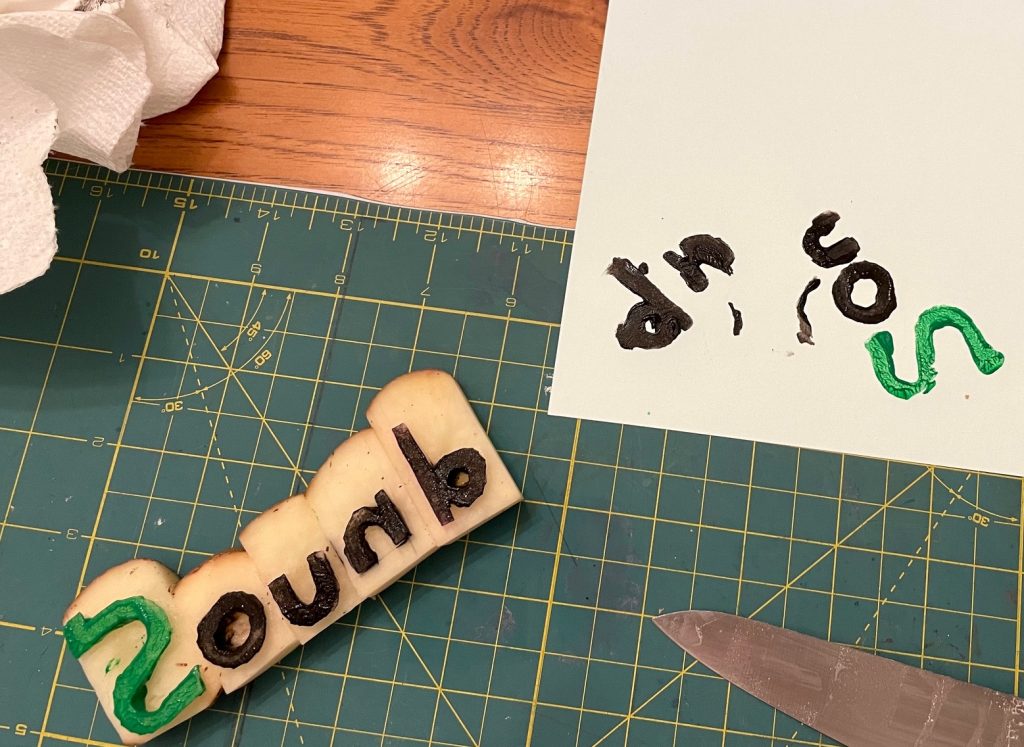

Because I had carefully focused on the width, depth, and surface angle of the potato pieces, it allowed me to use the knife blade as an alignment tool; using one hand, I squeezed the pieces together while using my other hand to lift and flip them into place. Although my first attempt at printing was aligned quite well, I didn’t pay attention to the character order: the word was misspelled :(.

Oops!

In my second attempt, when squeezing and lifting the pieces into place, the blocks slipped and fell onto the paper in a mess.

Disaster during placement

I changed my approach in the third attempt, painting the ink and then placing each block individually, essentially casting all the effort for ensuring alignment out the window. Each piece was placed visually, but freehand, to form the first print.

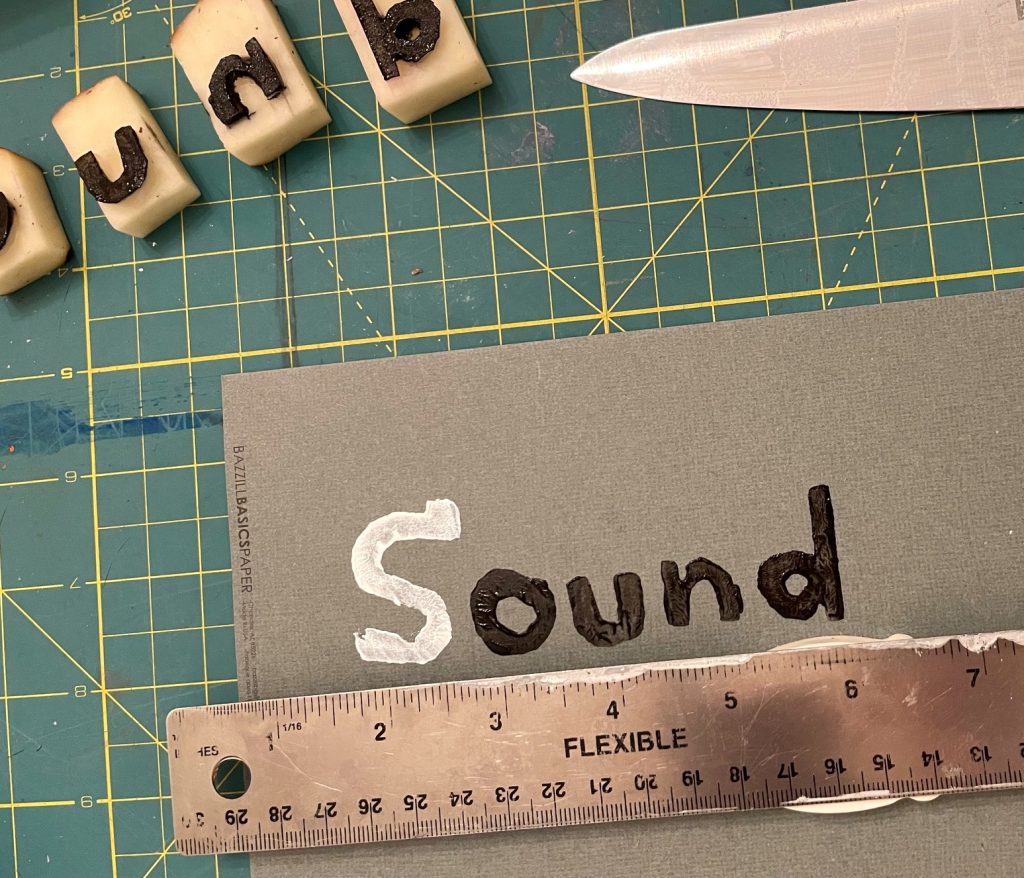

Happy with the result, but unhappy with the approach, I adjusted the process for the second print by using an elevated ruler as a guide. Although the kerning remained freehand, I was satisfied that the letters were controlled horizontally.

A better approach: one-by-one using a guide.

I wanted to experiment with different first letter colours because this appears to have been a common occurrence in medieval text.

Final print

My printing exercise took approximately two hours, and it is clearly a technical pursuit because of the importance of precision. Any mechanical systematization would have needed to consider the impact of temperature on the expansion or contraction of metal, the viscosity and drying time of ink, and the complexity of the operational labour. However, as Innis documents, the unbelievable explosion of print as a result of this technology (roughly 200 pages/hr to 768,000 pages/hr!) clearly demonstrates it value (Innis, 2007).

References

Innis, H. (2007). Empire and communications. Dundurn Press.

McLuhan, M. & ProQuest (Firm). (2011). The Gutenberg galaxy: The making of typographic man ([New];1;New;). University of Toronto Press. https://go.exlibris.link/tqv0cls4