Davies, Scott and Neil Guppy. “Race and Canadian Education”. Racism and Social Inequality in Canada. Ed. Saizeqich, Vic. Thompson Educational Publishing. Toronto. 1998. Print.

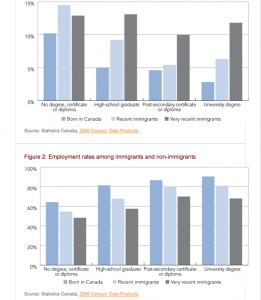

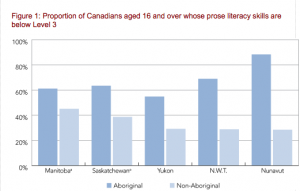

Scott Davies and Neil Guppy collaborate on this article and are truly a powerful intellectual pairing. Neil Guppy is a Professor in the Department of Sociology at UBC Vancouver and Scott Davies is a Professor at McMaster University. Davies and Guppy offer a surprisingly contrasting view on racism in Canadian school systems in their article in Racism and Social Inequality in Canada. While they recognize that “any social group that faces disadvantages in our schools will likely also face problems in the labour market and in cultural spheres” (Davies 131), ultimately they argue that our attempts at multiculturalism and “the continual preoccupation with race and ethnicity deflects attention from . . . far more enduring sources of educational inequality” (153). First Davies and Guppy discuss many of the widely published academic work that they are working to disprove. These works argue that “our schools are said merely to offer the appearance of equal opportunity . . . Students who fail in school . . . are usually poor students, ethnic minorities and females” (Cited in 132) and “implicitly promote the superiority of a culture that Canadians inherited from Europe” (132). They continue to conclude that “this type of subtle racism, according to this argument, is not overt, nor is it expressed as hatred. Nevertheless, it is said to be potent. because it ‘disables’ minority students, socializes them into failure and condemns them to permanent marginality in the labour market” (cited in 132-3), but ultimately Davies and Guppy’s “aim is to examine the evidence and reasoning that underpin claims of institutional racism in Canadian education . . . [through] quantitative evidence on equal opportunity in contemporary Canadian education”(133). Afterwards they “attempt to explain why education in Canada is becoming increasingly racialized” (133). Despite recognizing that “Aboriginals received the smallest share of university degrees” (138) and that they face a “clear case of blocked attainment” (140), they ultimately conclude there is no evidence of racial impediment in the education system. Although they presented much concrete evidence, I decided to research further. As you may see that in the first graph their thesis is supported, but it is clear by the 2nd graph that there is clearly still a problem with racism in our country. Furthermore the third graph shows that while immigrants and other minorities succeed in school, it is clear that the Aboriginal population is still discriminated against. Even Davies and Guppy agree with that fact, citing an abysmal average of 1.575% of the populous holding a university degree.

Works Cited

- Davies, Scott and Neil Guppy. “Race and Canadian Education”. Racism and Social Inequality in Canada. Ed. Saizeqich, Vic. Thompson Educational Publishing. Toronto. 1998. Print.

- Multiple Authors. “More education, less employment: Immigrants and the labour market”. Visual. Lessons in Learning. Canadian Council on Learning. Oct 2008. Accessed July 23rd. Web.

- Multiple Authors. “Improving literacy levels among Aboriginal Canadians”. Visual. Lessons in Learning. Canadian Council on Learning. Sept 2008. Accessed July 23rd. PDF

By James Long

Dowell, Kristin L. “Aboriginal Diversity On-Screen.” Sovereign Screens. Lincoln: U of Nebraska, 2013. 76-105. Project Muse. Web. 19 July 2015.

Anthropology scholar Dowell has done extensive research on what she calls the “visual sovereignty” of Aboriginal culture in media. In this chapter, Dowell “analyze[s] the ways in which Aboriginal media intervene in the Canadian national mediascape to impact on-screen representations of Aboriginal people” by “exploring the impact of APTN [the Aboriginal People’s Television Network] on Aboriginal media production” (77). She also explores the representation of mixed-blood and two-spirit Aboriginals, and mentions the success of youth programming—which pushes us to meditate on the effect of media like didactic cartoons on youth. It seems that a central tension Dowell has found in speaking with industry professionals such as Jeff Bear is a crossroads between assimilating to mainstream media culture (in order to create awareness for unique Aboriginal stories)—or to create a separate Aboriginal space to speak in traditional ways not yet well-received by the mainstream industry. Aboriginal artists themselves seem divided on this crossroads.

This chapter of her book first describes the frustrations Aboriginals often face when working in the media industry with mainstream colleagues. For example, when Kamala Todd interviewed chiefs for a news program, she did not cut their interviews because traditionally, elders should not be interrupted when telling their stories; but she had to fight against the non-Aboriginal producers in the room who wanted to edit the interviews to speed them along (Dowell 81-82).

APTN’s mandate is to share Aboriginal life with other Canadians (Dowell 84), and they seem to be doing this well, because most of the people who watch it are non-Aboriginal (Dowell 77). This was surprising for me, and has made me optimistic that people ARE interested in Aboriginal cultural expression; we just have to feed it to them right. Ironically, filmmakers and scholar Lorna Roth worry that rural Aboriginals have limited access to the channel on reserves, or that some city-dwellers cannot afford cable (Dowell 88).

A shortcoming of APTN is that, with its existence, many mainstream outlets reject Aboriginal content by telling its creators that it belongs on APTN instead of on their channels (Dowell 91-92). Producer Dorothy Christian describes her dream of having aboriginal content across all outlets, but filmmaker Odessa Shuquaya disagrees: “Why don’t we create our own mainstream, an Aboriginal-stream?” she says (qtd. in Dowell 92).

Another shortcoming—a “common refrain . . . from Vancouver filmmakers” (Dowell 89) is the lack of West Coast-related content on APTN, as most of the channel’s programming is focussed on the North, says filmmaker Barb Cranmer (90). This is unfortunate, because BC is perhaps the most exciting arena for Aboriginal current affairs right now because of its ongoing treaty negotiations and protest movements (90). Indeed, having only one Aboriginal-dedicated channel is problematic because it conglomerates Aboriginal culture as a whole, as opposed to representing it as a mosaic of many unique cultures (as it is). We tend to simplify Aboriginal culture as “Aboriginal Culture,” not Squamish culture or Cree culture.

Fortunately, APTN is a great place to represent mixed-blood and Metis experiences because individuals from these communities tend to feel alienated within the larger Aboriginal community (Dowell 94-95 footnotes?). The two-spirit community has also found comfort in the media, as many filmmakers have moved into queer-(and film-) friendly Vancouver, claiming that the homophobia that exists in rural reserve communities is a leftover colonial effect (Dowell 100-101).

Personally, I think APTN is a good first step…but perhaps an indicator of success is when we don’t need it anymore. “[V]isual sovereignty does not imply a separation form engagement with Canadian society[,]” Dowell reminds us, “but rather reflects the overlapping citizenship of Aboriginal people who hold citizenship in their Aboriginal nations as well as Canadian citizenship (104). A question for the future would be: how will APTN fit in to the changing landscape of film/TV where people selectively stream shows online (through Netflix, for example), instead of committing to TV channel bundles? How can we ensure that our unique Canadian and Aboriginal voice will not be drowned out by popular media created by our (probably more well-funded) neighbours south of the border? Perhaps a good place to start is to encourage young artists to become future leaders in the industry. Or start introducing Aboriginal programming into the mainstream; the good news is, there is evidently a demand for it, and Canadians want to learn more about the Aboriginal heritage of this country.

Works cited

- “About.” Aboriginal People’s Television Network. Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, n.d. Web. 30 July 2015.

- “Negotiation Update.” BC Treaty Commission. BCTreaty.ca, n.d. Web. 30 July 2015.

- Snider, Mike. “Cutting the Cord: The TV Times, They Are A-changing.” USA Today. Gannett Satellite Information Network, 9 Nov. 2014. Web. 3 Aug. 2015.

- “Sovereign Screens – University of Nebraska Press.” University of Nebraska Press. University of Nebraska: LIncoln, n.d. Web. 03 Aug. 2015.

- “Two-Spirit Community.” Researching for LGBTQ Health. University of Toronto and Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, n.d. Web. 03 Aug. 2015.

By Charmaine Li

Fitzgerald, Michael Ray. “‘Evolutionary Stages of Minorities in the Mass Media’: An Application of Clark’s Model to American Indian Television Representations.” The Howard Journal of Communications 21.4 (2010): 367-84. Taylor and Francis. Web. 9 July 2015.

In this paper, Dr. Michael Ray Fitzgerald from the University of Reading applies Cedric C. Clark’s four-stage model of minority media representation to a study on the representation of Native Americans in pop culture media. Although his research is focussed on American representation, I believe it is a useful introductory article to the subject of minority media representation in general. I also believe it is applicable to Canadians as the border between American and Canadian popular media is quite porous. We in Canada consume as much (if not more) American entertainment as Canadian entertainment.

Fitzgerald begins by summarizing the Clark model’s four stages:

1. Non-recognition: A given minority group is not acknowledged by the dominant media to even exist.

2. Ridicule: Certain minority characters are portrayed as stupid, silly, lazy, irrational, or simply laughable.

3. Regulation: Certain minority characters are presented as enforcers or administrators of the dominant group’s norms.

4. Respect: The minority group in question is portrayed no differently than that any other group. Interracial relationships would also not appear extraordinary. (Fitzgerald 368)

Fitzergerald acknowledges that this model has been found by other scholars as imperfect—and it is worthy of note that it was originally used more for investigating the representation of African Americans in media (368). He also notes that “[a]n arguable weakness in Clark’s model is that it suggests a linear or chronological progression,” while Native American representation has, through his findings, “undergone more than one stage of Non-recognition” (380).

In his study of Native American representation throughout American media (the methodology of which he delves in considerable detail), Fitzgerald found that “most American Indian characters are set in a distant, ‘historic’ past” and “[t]he more prominent the character and the more modern the setting, the more likely he (almost always a man) was to be a regulator” (376). When we think of Aboriginals, we don’t often think of them in Tshirt-and-jeans walking down a 21st-century street, do we? Drawing on Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water, we don’t see Lionels and Eli’s and Charlie’s and rarer still, women like Alberta. We often don’t see complex people capable of fulfilling more than simple roles.

Personally, I find the Regulation stage most interesting. It’s as if media is trying to “over-correct” itself by shouting “Minorities can be responsible too! Look at them not just obeying the law, but enforcing it!” We see stage 3 portrayed (perhaps satirically) in Green Grass Running Water by the characters of Eli and Charlie. They’re educated Aboriginal lawyers, but they’re not regarded highly by their Aboriginal peers. Fitzgerland cites additional scholars (Scotch and Jhally & Lewis) that “simply ‘flipping’ negative stereotypes to positive ones is not much of an improvement” (380). This brings to mind the age-old “noble savage” trope, like this girl:

Kids adore Disney’s Pocahontas, a tale from the past. And adults have their own Pocahontas too in Terrence Malick’s (The Tree of Life, Days of Heaven) impressionistic take on the tale (click for one viewer’s analysis of the Native portrayal in that one). As a western audience, we see less things like this:

Digging Roots is a Juno award-winning Native Canadian music group that uses western instruments (like guitars and drums) to perform music that fits mainstream, contemporary taste while honouring their traditions with cultural references throughout (great music, go have a listen!). The author of the article I linked to above (Lisa Charleyboy) writes: “I can’t wait until the day that the Juno Awards begins presenting this award on it’s televised portion of the show. I do feel that as the First Nations population and presence increases in Canada, that this will happen.” I’m not sure if this has changed in 2015.

Will we reach Stage 4 anytime soon? Digging Roots’ Juno award exists in a separated “Aboriginal” category. While I understand the creation of a separate Aboriginal category is an initiative to create equal opportunity in a white-dominated industry, it discomforts me that even in the arts, we have the need to designate Aboriginals as the “other,” and I’d personally wish to see an arena where affirmative action is unnecessary.

Works cited

- APTN, “Spring to Come – by Digging Roots.” Online video clip. YouTube. YouTube, 28 Feb. 2011. Web. 26 July 2015.

- Charleyboy, Lisa. “Digging Roots Wins a Juno.” Urban Native Magazine. Urban Native Magazine, n.d. Web. 26 July 2015.

- “Colors of the Wind.” Online video clip. Disney. Disney entertainment, n.d. Web. 26 July 2015.

- Rohrer, Sheila Ann. “Native American Portrayal in “The New World” (Pivotal Film).” Sheila Rohrer. Pennsylvania State U, 8 Nov. 2009. Web. 26 July 2015.

- Viruet, Pilot. “Are This Season’s Diverse Shows Ushering in a New Era of Multicultural Television?” Flavorwire. Flavorpill Media, 04 Mar. 2015. Web. 03 Aug. 2015.

By Charmaine Li

Fitzgerald, Michael Ray. Native Americans on Network TV: StereoTypes, Myths, and The “Good Indian” Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. Print.

In his book “Native Americans on Network TV: Stereotypes, Myths, and the ‘Good Indian’”, Fitzgerald explores the multiply ways in which Native Americans have been misrepresented in North American media throughout history. Fitzgerald explores the various stereotypes and myths of Native American culture and people that were manipulated to “fit whatever political or cultural concepts that may [have been] useful for…US society in any given era” (Fitzgerald xii). In general, depictions of the Native American “Other” on the big screen have consistently fallen into one of two possible extreme characterizations: the “evil, murderous enemy” or the “innocent [Good Indian that is a]…helpless child of nature” (Fitzgerald 54).

Characters like Disney’s widely popular and adored Pocahontas helped perpetuate this latter image of the “Good Indian”, a Native American that openly embraced “Euro-American domination” (Fitzgerald xii). Moreover, fictional figures from literature that found their way onto the television like Robinson Crusoe’s Friday, continued this endorsement of a subordinate and subservient “Good Indian” that despite his broken English, “recognize[d] the white man’s natural superiority” (Fitzgerald xiii). One of the most prominent examples of this “Good Indian” depiction is Lone Ranger’s Native American sidekick, Tonto. Tonto is the epitome of a desperate, helpless “Other” who “eagerly welcomes the white man’s superior law and order” (Fitzgerald 43). Characters like Pocahontas, Friday, and Tonto all served to legitimize white man’s “presence here…[by] project[ing] onto Indian characters the uncertainty non-natives feel about…[their] history and…right to occupy the land” (Fitzgerald xii). Fitzgerald’s article reveals the ways in which the body of the “American Indian” in television is “other-ized [as a] foreign body to be looked at” (Fitzgerald 63). Therefore, Native American people and culture are not represented as equals, but rather objects to be used, observed and manipulated to serve the needs of non-natives.

Fitzgerald explores how these depictions and distortions of Native Americans to fit the dichotomy of the Good vs Bad Indian can be traced back to televised programs and shows during WWII and the Cold War. Depictions of the savage and violent Indian disappeared and were replaced by a more sympathetic portrayal because of the “genocides of World War II” (Fitzgerald xxx). These stereotypes of Native Americans being abused and exterminated “by US forces…became a severe liability on the international stage” (Fitzgerald xxx). Representation of Native Americans on television were therefore politically charged and manipulated to serve the United States and their image as the “leader of the Free World”, rather than actually accurate representations “connected to the interests of Indians themselves” (Fitzgerald xxx).

Part of our intervention conference project needs to focus on the ways in which Native Americans, and their depictions in various forms of mass media, are used as a tool for non-native goals and ambitions. To attack the misrepresentation and distortion of Native Americans at the level of television and media is to attempt an intervention in one of the most pervasive and modern forms of literature and oral tradition in today’s 21st century. Without it, we cannot have a fully productive discussion of how to change the landscape of Canadian Literature, and its inclusion of Native American people and culture, for future generations to come.

Works Cited

- Canale di fancyfool10, “Pocahontas – At First Sight.” Online video clip. Youtube. Youtube, 22 Aug. 2009. Web. 26 July 2015.

- Cory St. Croix, “Crusoe- Friday God Debate.” Online video clip. Youtube. Youtube, 11 Oct. 2012. Web. 26 July 2015.

- FitzGerald, Michael Ray. Native Americans on Network TV: StereoTypes, Myths, and The “Good Indian” Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014. Print.

- Rothman, Lily. “Johnny Depp as Tonto: Is The Lone Ranger Racist?” TIME Magazine, n.d. Web. 25 July 2015.

By Freda Li

Gallagher-Mackay Kelly, Annie Kidder, and Suzanne Methot. “FIRST NATIONS, MÉTIS, AND INUIT EDUCATION: Overcoming gaps in provincially funded schools”. People For Education. Toronto. 2013. Web. August 2015.

This article’s data and records are based off of research done in the province of Ontario, Canada. The subject matter touches upon the curriculums designed in the public school education systems of Ontario. It emphasizes on the fact that the majority of public schools lack adequate education about the “rich cultures and histories of First Nations, Metis, and Inuit peoples”. The ministry of education claims that it is important that students should have greater knowledge on these subjects, and Ontario’s Kindergarten to Grade 12 curriculums require mandatory education about First Nations studies and history of Canada. However, in a survey collecting data about education program in Ontario, it stated that 51% percent of elementary schools and 41% of secondary schools reported no education plans of FN studies and history. Many teachers admit that the curriculum already possesses so many subjects and learning objectives that many of the topics are spread thin. The principal of Waterloo Catholic DSB Elementary School stated that

“We are honestly doing the best we can to ensure that our students understand and have opportunities to learn more about the cultures and histories of Aboriginal peoples. We probably do not give it the time it deserves, not because we don’t care, but because there are too many priorities.”

Many schools fail to meet the ministry of education’s objectives to teach First Nations studies and history ultimately because of common misconceptions, such as the assumptions that in order to teach these subject matters, there needs to be a large number of Aboriginal students. Despite this fact, 92% of pubic elementary schools and 96% of public high schools have First Nations students attending these institutions. Nevertheless, there are a number of schools (about 13% of elementary schools, and 30% of high schools) that do provide adequate frameworks for First Nations studies to their students, by promoting this type education in all grades and integrating the subjects over the school year.

Researchers, advocates and professor’s that evaluate the Toronto District School Board’s Urban Aboriginal Education Pilot Program, state that there could be improvements within the curriculum if students (First Nation, or non First-Nations, status or no-status), had a thorough understanding of treaties and their roles, and how they affect both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples. Additionally, misconceptions and stereotypes that stigmatize and disadvantage First Nation’s people should be challenged and questioned. If student’s who were not exposed to reserves or areas in Canada where many First Nation peoples reside, it is suggested that students should have personal relationships with First Nations people themselves, which aid in deeper understanding, and a tactful approach to First Nations studies taught in schools. York Professor, Susan Dion, claims that students should develop a deeper understanding of First Nation’s cultures, that there should be a larger exposure to Aboriginal authors, and that students should learn from Aboriginal artists.

Personally, I agree with the tactics suggested by the researchers who evaluate the Pilot Programs in Toronto. These suggestions are hands-on approached for students to not only understand the theory aspects of First Nations studies, but to also integrate more knowledge through First Nations’ art, First Nation authors and writers, and personal experiences through making relationships with communities of First Nations people. I do believe however that a more in depth First Nations education program could benefit from integrating forms of media into the curriculums. Today, the youth in our culture have constant exposure to forms of media, such as the internet, television, movies and advertisements. These mediums do not necessarily challenge the stigmatized ideas of how First Nation’s peoples live, their history, and their involvement within current Canadian affairs. I believe the education systems may not be moving fast enough with the times…if a message needs to be spread to the masses, media is the quickest and most impactful way of doing so. Children catch on fast, and exposing them to information through methods of media could drastically enhance their knowledge about First Nations’ studies in Canada. Regardless, if media outreach was an educational tactic, forms of the media would have to develop to begin teaching the masses in the first place.

Works Cited

- Aboriginal Art. The National Gallery of Canada. 2015. Web. August 2015.<https://www.gallery.ca/en/about/941.php>

- Gallagher-Mackay Kelly, Annie Kidder, and Suzanne Methot. “FIRST NATIONS, MÉTIS, AND INUIT EDUCATION: Overcoming gaps in provincially funded schools”. People For Education. Toronto. 2013. Web. August 2015. <http://www.peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/First-Nations-M%C3%A9tis-and-Inuit-Education-2013.pdf>

- Eigenbrod, Renate, Georgina Kakegamic and Josias Fiddler. “Aboriginal Literatures in Canada: A teacher’s resource guide”. The Curriculum Services Canada Foundation. CSC. 2003. Web. August 2015. < http://curriculum.org/storage/30/1278480166aboriginal.pdf>

By Arianne LaBoissonniere

Hackett, Robert. “Remembering the Audience: Notes on Control, Ideology and Oppositional Strategies in the News Media”. Popular Cultures and Political Practices. Ed. Gruneau, Richard B. Garamond Press. Kingston, Ontario. 1988. Print.

Robert Hackett, a Professor of Communication at SFU, article in Popular Cultures and Political Practices remains incredibly, and perhaps even more, relevant despite its age. Hacket along with several other “cultural studies researchers … stress[…] that cultural practices and meanings can be implicated in modifying, reproducing, resisting and/or transforming social relations of power, domination and inequality” (Hackett 83) through the manipulation of media. At the time of writing this article Hackett suggests that “Canadians spend about seven hours a day with mass media—more than any other activity except work and sleep” (83) and likely this number has increased dramatically with the introduction of services such as Netflix, but through my quick survey of the research it seems to be a contested issue. Many critics argue what should be considered media and average hours consumed range from five to almost nine hours a day. Either way media is clearly a powerful force in shaping Canada. Hackett attempts to answer the questions, “in what ways do the media play a hegemonic role in Canadian culture?” and “What political strategies should be pursued in relation into the existing media and what alternative policies should be proposed and fought for?” (84). Hackett analyzes the state of mass media in many ways, but the kernel of the problem that he identifies is that “members of the media elite disproportionately came from a privileged upper-class background” (84), and I would like to add that even today they lack a diversity of culture and social standing. Furthermore, he found that this history prompted them to “reinforce the existing political and economical systems” of inequality. He then offers several modes of intervention, the most interesting of which include; “Alternative Media” (94), “Media Criticism”, “Internal Reform”, and “Audience Resistance” (96). Hackett suggests “it would be worth exploring and debating the potential for an opening for alternative journalism created by the emergence of new user-paid media services” (95) and I think with the emergence of new media such as Youtube and others the opportunities for alternative media have expanded. The popularity of this media however struggles due to production quality and the “process of audience fragmentation associated with the development of specialized services […] ghettoiz[ing] alternative electronic journalism” (95). I have attached two examples of such media that both operate simultaneously as alternative media, media criticism, and audience resistance. Hackett’s article predicts many of the modern day solutions that need support and to be expanded to include wider media outlets.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=svOxBkbOHXY

Works cited

- The Young Turks. “Fox Guest So Vile & Sexist Even Hannity Cringes”. Youtube Video. Posted May 2015. Accessed 22nd July 2015. Web.

- Hackett, Robert. “Remembering the Audience: Notes on Control, Ideology and Oppositional Strategies in the News Media”. Popular Cultures and Political Practices. Ed. Gruneau, Richard B. Garamond Press. Kingston, Ontario. 1988. Print.

- Winnipeg Alternative Media. “Is Winnipeg really the most racist city in Canada?”. Youtube Video. Posted Jan 2015. Accessed 22nd July 2015. Web.

By James Long

Ottmann, Jacqueline, and Lori Pritchard. “Aboriginal Perspective and the Social t2009. Web. August 2015. <http://www.mfnerc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/5_OttmanPritchard.pdf>

Alberta Education implemented a program in 2009 called Alberta Social Studies Program of Studies, catered towards the education of Kindergarten to Grade 12 students The program aims at improving teaching Aboriginal studies subjects within school curriculum, while reflecting the nature of the 21st century learners. The program emphasizes the idea of “multiple perspectives”, which draws upon three elements

1 – Knowledge and understanding

2 – Values and attitudes

3 – Skills and Processes

These “multiple perspectives” include fostering concepts of our society that are democratic, bilingual, pluralistic, and respectful towards Canada’s diverse ethnicities. It touches upon Canada’s multiculturalism and reflects Aboriginal and Francophone perspectives.

In order for the program to take effect and run smoothly, teachers are advised to be more aware of their own perspectives, and how they present them to the students in their classrooms. In other words, teaching with the basis of fundamental respect towards Aboriginal cultures is necessary, so that students can understand the concepts of respecting diversity in individuals, cultures, and society. This includes being aware of one’s own perspective and considering others’ perspectives, as well. By doing this, students can avoid stereotyping, and speak out against prejudices, racism and discrimination.

Aboriginal people must be involved and present when developing the curriculum of “multiple perspectives”, because their worldviews must be incorporated into the subjects. Their input will help shape the program and navigate the vision so students can have more in depth education on Aboriginal Studies.

Gregory Cajete elaborated on what education should consist of, and how effective it can be when applied through engagement.

“Education is an art of process, participation, and making connections. Learning is growth and life process; and Life and Nature are always relationships in process. Learning is always a creative act.” (Cajete, 1994)

Materials studied in classrooms such as specific authors and books, should be considered as well, since they play a huge role in shaping course subjects. Teachers are advised to selectively pick materials such as readings, or audio-visuals that are approved by Aboriginal organizations, so that they are non-biased, and do not stereotype or generalize First Nation, Inuit or Metis cultures. Claims of incorporating oral history into formal education systems to teach Aboriginal studies is also strongly considered, since story telling plays a major role in all Aboriginal cultures. In Antone and Cordoba ‘s study, they interviewed many Aboriginal people, and one interview claimed

“That’s how we do the teachings through storytelling and legends, and that was our way our kids learned; that was teaching. The right way and the wrong way, you could learn through the legends for thousands of years, you didn’t have to have degrees or anything. So we learned a whole lot about life through storytelling and it’s important that we still continue that process because more so now kids are having tremendous difficulties in school” (Antone, E., & Cordoba, T. 2005, pp. 5-6).

Story telling is engaging and aims at teaching students how to use critical thinking, and would benefit all students to help learn interactively. In Jagged Worldviews Colliding, Little Bear expresses that “making Essential Connections When we don’t know each other’s stories, we substitute our own myth about who that person is. When we are operating with only a myth, none of that person’s truth will ever be known to us, and we will injure them – mostly without ever meaning to. (Wherner & Smith, 1992, p. 380)

Statistic Canada released a report in 2005 stating that the Aboriginal population in Canada, which includes First Nations, Métis and Inuit, reached the one-million mark at 1,172,790. Recent data from 2011, from the National Household Survey (NHS), state that the population is now roughly around 1,400,685 (Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Metis and Inuit. Statistics Canada). In 2001, studies showed that 42% of Aboriginal students from the ages 15 and above did not get high school diplomas, and 31% of non-Aboriginal students in the same age group did not receive diplomas, either (Human Resources and Skills Development Canada, 2009). These percentages demonstrate that teaching methods and practices need to change in order for a more successful graduation process. The “multiple perspective” approach is quite complex, and requires understanding from “program directors, policy makers, school administration, and teachers if they are to make systemic, sustained difference for Aboriginal students in terms of educational and holistic well being” (Ottmann, 2009). Improving learning for all students to achieve success in their education, and to learn in terms of the “multiple perspective” is necessary to meet the requirements of the Alberta Education Program of Studies, and to positively impact the Alberta school curriculum, and learning processes for the students.

Personally, I find that the Alberta Social Studies Program of Studies possesses great intentions to teach students with a more in depth approach to Aboriginal studies however I am skeptic that results will occur right away. An implemented educational plan such as re-designing curriculums, changing course materials, informing teachers for new methods of teaching requires a lot of time, and funding. A project that aims to create more perspectives should be observed through a number of decades to view results. I do admire the incorporation of oral traditions when teaching these subjects, and the approach of using audio-visuals, and readings that are approved by Aboriginal organization. By doing this, the materials in class are set up to cease stereotypes and preconceived notions students may possess in their psyches about Aboriginal people in Canada. Perhaps the audio-visual components used in classrooms could utilize sources from the media that are Aboriginal organization approved, as well. If this plan is well executed, “multiple perspectives” in education could pave the way for new ideas, and approaches of how cultures in Canada will interact an engage in future generations.

Works Cited

Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Metis and Inuit. Statistics Canada. Government of Canada. 28 March 2014. Web. August 2015.

<http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-011-x/99-011-x2011001-eng.cfm>

Aboriginal Worldviews. Dragonfly Consulting Services Canada. 2012. Web. August 2015. <http://dragonflycanada.ca/resources/aboriginal-worldviews/>

Antone, E., & Cordoba, T. (2005). Re-Storytelling Aboriginal Adult Literacy: A Wholistic Approach. Paper presented at the National Conference On-Line Proceedings. University of Western Ontario.

Bradford, Shannon. Multiple Perspectives: Building Critical Thinking Skills. Read Write Think. International Literacy Association. Columbus, New Jersey. 2015. Web. August 2015. < http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/multiple-perspectives-building-critical-30629.html>

Cajete, G. (1994). Look to the mountain: An ecology of indigenous education. Skyland, NC: Kivaki Press

Canadians in Context – Aboriginal Population. Employment and social development Canada. 14 August 2015. Web. August 2015. <http://well-being.esdc.gc.ca/misme-iowb/.3ndic.1t.4r@-eng.jsp?iid=36>

Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. (2009). Indicators of Well being in Canada: Learning, Educational Attainment. Retrieved May 25, 2009, from http://www4.hrsdc.gc.ca/.3ndic.1t.4r@-eng.jsp?iid=29

Integrating Aboriginal perspectives into curricula: A resource for curriculum Developers, Teachers, and Administrators. Manitoba Education and Youth. 2003. Web. August 2015. <http://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/docs/policy/abpersp/ab_persp.pdf>

Ottmann, Jacqueline, and Lori Pritchard. “Aboriginal Perspective and the Social t2009. Web. August 2015. <http://www.mfnerc.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/5_OttmanPritchard.pdf>

Little Bear, L. (2002). Jagged worldviews colliding. In M. Battiste (Ed.), Reclaiming indigenous voice and vision (pp. 78-85). Vancouver: UBC Press

Wherner, E., & Smith, R. (1992). Overcoming the Odds: High Risk Children from Birth to Adulthood. New York: Cornell University Press.

Western Canadian Protocol for Collaboration in Basic Education. (2002). The Common Curriculum Framework for Social Studies: Kindergarten to Grade 9. Winnipeg: Manitoba Education, Training and Youth Cataloguing in Publication Data.

By Arianne LaBoissonniere

Rollins, Peter. Hollywood’s Indian: The Portrayal of the Native American in Film. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2003. Project MUSE. Web. 22 Jul. 2015.

Peter Rollins starts off his article “The White Man’s Indian” by explaining why the portrayal of Native Americans in television and film is worth our time and concern. For Rollins, “Film [in and of itself] is a literary form…[that just like novels, short stories, and other forms of literature, has the] purpose…to tell a story” (Rollins 30). In fact, the form of oral history that attempts communication through images, rather than words, takes on a more difficult task because of how media forms allow viewers to “tak[e] in [a] message on a sensual and emotional level” (Rollins 32). Unfortunately, the story that has been told of Native American people and culture in Euro-North American media is one that has been manipulated to serve the “current interests of the dominant culture” (Rollins 28).

Portrayals of Native Americans have failed to hold any authenticity and accuracy, but rather a representation of what Rollins dubs, the “White Man’s Indian”. Therefore, even when Native Americans are portrayed as the moral and honourable “Good Indian” it is only to support goals of the white man and the subsequent “technical and business related production decisions” rather than a true concern for “their affect[s] on the screen image” (Rollins 30). This mainstream image has posed many concerns for the understanding and treatment of Native American culture and people by non-natives in our nation because “historians, anthropologists, and other professionals” must work even harder to “dispel these [inaccurate yet] popular concepts” and assumptions (Rollins 29).

Part of our conference project concerns and goals involve finding ways to use education and media to provide a more accurate representation of Native American culture that moves away from these highly inaccurate “popular concepts”. Many of the concerns with misappropriation and distortion of Native American culture and people is a result of the image of Native Americans on the big screen. Their representation is often dictated by how “moviegoers expect Indians to be presented…in a characteristic way (Rollins 33). Rollins explores various detrimental efforts to fulfill these “expectations”, like the hiring of non-native actors to fill roles meant for Native Americans merely because producers “felt they looked better” (Rollins 33). This is an issue of disrespect and misrepresentation that continues to be perpetuated today, with the most recent example being the controversy surrounding Adam Sandler’s most recent film. Moreover, these Native American characters, even when portrayed more or less “accurately”, are often “flat characters [with]…little time…spent in developing the[ir] screen personalities” (Rollins 32). Rollins disappointingly points out that often, they are more just “part of the setting [or background…more than…a character in [their] own right” (Rollins 32).

Works Cited

- Nguyen, Tina. “Native American Explains Why He Walked Off Adam Sandler Set: ‘Was A Total Disgrace.'” MEDIATE. n.d, Web. 26 July, 2015.

- Nittle, Nadra. “Five Common Native American Stereotypes in Film and Television.” AboutNews. n.d., Web. 28 July 2015.

- Powelson, Rick. Good Indian/Bad Indian. Comanche University of The 49. 20 Jan. 2005. Web. 25 Jul. 2015.

- Rollins, Peter. Hollywood’s Indian: The Portrayal of the Native American in Film. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2003. Project MUSE. Web. 22 Jul. 2015.

By Freda Li

——–

Addendum: static images used on this site

Background image (cedar wood grain): “Cedrus wood”. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. MLA citation: Brodo. Cedrus Wood. Digital image. Wikimedia Commons. Wikimedia Foundation, 1 Feb. 2006. Web. 30 June 2015.

Header image: own work, from Charmaine’s Instagram

Hey,

I really like a lot of the points you have put here. James’ articles mentioning that society plays a large role in altering inequality, and as per your group’s main intention to alter mass media portrayals to reduce stereotyping. The “reinforce[ment] of existing political and economic systems” seems to connect with Charmaine’s article on Fitzgerald about the four stages of minority representation. It seems interesting to note that several minority races are in the Regulation stage, and that they, like the Aboriginals/First Nations people, have moved between stages 1-3 but very rarely to 4 (respect). Another point that connects between James’ and Charmaine’s articles is “educational inequality”, media expressing their idea of multiculturalism is inaccurate and when the media isn’t stereotyping a culture it almost idealizes it (puts it on a pedestal of sorts). It’s possible that even today, as in Freda’s research on Rollins, these portrayals may be inaccurate because they promote someone’s goals, because they’re not helping the portrayed ethnicity.

Connecting my research with James’, subtle racism has become more prominent due to the removal of institutionalized racism. People now have implicit stereotypical beliefs about other groups that come out subtly. People within racial/ethnic groups can be affected by those internalized stereotypes they hold about their own groups as well, something called “stereotype threat” (http://www.reducingstereotypethreat.org/definition.html). This is in one part a factor that contributes to the “racial impediment in the educational system”, and alterations to a teacher’s behavior due to these implicitly held racist beliefs.

Great work,

-Landon

Thanks very much for your comment.

I’m happy to see that you can see the connections we are trying to make with our choices of articles. I think we as a group have really tried to portray that in order to start fixing the imbalances in our society one answer to one problem will not be enough. Our society, as all others, interacts with itself in a circular manner. Everything affects everything else somehow. I had not heard the term “Stereotype threat” till you mentioned it just now, I feel like that may help my research quite a bit. Thank you for that.

As a future teacher I really believe that proper education has the power to change the future, but like I mentioned earlier everything affects everything. So many limitations and guidelines are placed on our educational system it stunts our growth as a society.

Thanks again for your comment.

James, I’ve always loved your idea of a circular-moving world 🙂 It’s a great thought that if we only intervene at some point of the [vicious] circle, the effects we create will ripple and radiate out. I think that’s why it’s great you’re pursuing education because that’s a very critical point of the circle.

Still, I think it’s good to have a—even if somewhat idealistic—teleological goal in mind. I hope one day there will be all sorts of folks in the “upper echelons” of the world’s major industries, especially media. Making real decisions. Representing everyone. A situation where merit determines your status in the industry, not who you know or what strings you pulled or what school you went to. Rather—in the case of the media industry—how good you are at entertaining.

One thing I learned as a mentee to a professional TV writer is that, once upon a time in the not-so-distant past, TV execs thought Sex in the City was “niche” show because it catered to women…because women are a “niche” audience. Er, despite being half the population…? I think TV execs have this assumption about what the public wants to see—monsters, witches, kung-fu—but what the public wants to see is shifting. As we can see with the amount of non-Aboriginal APTN viewers, public interest in Aboriginal issues are very real. Indeed, we hear about these issues all the time, I bet at least some of us genuinely want to understand them.

I think that was one of the best discoveries that were made during our research. At least for the sake of my own interest. The fact that so many Non-Aboriginal people view APTN really gives me hope that not only can things change but they likely will. It shows a true interest in the real culture as opposed to the colonized view we have so often been given through Disney productions or even children’s books. It shows that the population is becoming ready to listen and to learn. I know when I am a teacher I will surely plan to have Aboriginally created content to show my class. That being said I think it is important not to singular it out as such. This reasoning is why I hope that some of the shows produced by APTN will eventually be picked up by other networks and the artistic crew hired to keep its integrity. I hope that such worthy programming can reach the audiences it deserves.

My point to this comment is European-Canadian’s seem to finally be ready to learn, and through media and education we can see a brighter world.

Hey Landon, thanks for stopping by! I visited your site on stereotype threat; I’ve only vaguely heard about it before, but I can see how beneficial awareness of it is to our research. How do you think something like internalized stereotyping (stereotyping held by the stereotyped group) factors into telling that group’s stories in the media?

I think stereotype threat can be a debilitating obstacle for Aboriginal content creators, as pressure to “break out” of the stereotype might cause people to subconsciously censor themselves. I can’t speak for Aboriginals, but as a minority myself, whenever I’m expressing myself, I try rather hard not to mention things that are stereotypically “my race.” As a writer, I try to avoid so-called “ethnic writing.” So, I try not to write about kids of my race playing upper-level piano or being wickedly good at math (weird little examples, but I think you know what I mean 😉 ), in fear that someone in the audience will stereotype me. I think this stereotype threat has been reinforced in me since a young age, because growing up you always see authors with ethnic names talking about ethnic matters, as if that’s all they’re allowed to say.

It’s a double-edged sword though. I find it rather difficult, actually, to not talk about things tinged at least slightly with my personal cultural history. Because writing and expression is part of who I am, to not write about my experiences would make my writing come off as inauthentic.

So I’m quite certain Aboriginal creative types have this trouble too: negotiating the balance between authenticity and stereotype threat. That’s an obstacle I haven’t considered…so thanks again Landon!

Charmaine

If I were to take a guess as to how stereotype threat affects people of color creating stories/movies, I believe it would create a deep fear to not stereotype their own-race characters. The logic in this is that they are avoiding confirmation of these traits, and might make a character who is accurate, or more likely one who is a complete reversal of those traits (e.g. instead of being lazy they might be over-active or over-achieving). However, what might be more true is that media influences the creation of these internalized stereotypes through inaccurate portrayals of certain ethnicities/races.

Absolutely, the content creator would definitely run the possibility of censoring what they know about a culture. I understand what you mean, it does appear to be the case that many authors stick to writing either about their own ethnicity or (and based on what I’ve seen of popular novels) mainly European & Caucasian characters. It is this unique cultural experience that makes authors unique, and have their own perspective and take on how characters would react, and what the problems plaguing society are.

Landon

An excellent beginning – thank you. But, please format your bibliography in correct MLA format: alphabetical order, not by who posted – O.K.

And, I expect a few more hyperlinks, take another look at the examples in Lesson 4:2 – and be sure to check my latest blog post :).

Thanks, Erika

Hi Dr. Paterson, thanks for the head’s up! Will do.

Charmaine

Hi Charmaine,

The Fitzgerald article you used, titled “‘Evolutionary Stages of Minorities in the Mass Media’: An Application of Clark’s Model to American Indian Television Representations” is amazing! I thought I would take a moment to delve into some of the details a bit here. I think what you pointed out about the regulatory stage is spot on:

“3. Regulation: Certain minority characters are presented as enforcers or administrators of the dominant group’s norms.”

To me the qualifications for that part of Clark’s model seems to have the potential to create more obstacles and segregation than anything progressive or beneficial. I understand where Clark is coming from, in that minority figures come out of sidelines of the plot lines in their media representation, and join the focus that the dominant group is afforded by presenting themselves as “enforcers or administrators” of these norms. I think the main issue I have with this is the reality that the “dominant group’s norms” are not necessarily what we want to be upholding anymore. In encouraging minorities like Native Americans to uphold the norms, to assimilate into the dominant culture, we are not actually becoming more accepting of their culture or identity, or creating an environment where there is more understanding or acceptance.

I wonder if it truly is possible to jump from stage 3 to 4…I don’t see how going through stage 3 would set up the acceptance needed to achieve stage 4 in Clark’s model.

Hi James!

I just read your annotated bib summary on the article “Remembering the Audience: Notes on Control, Ideology and Oppositional Strategies in the News Media” by Robert Hackett and wanted to join in on the conversation. I found myself nodding as I read all the way through, so great choice! I definitely think its very in tune to what our interference project is about. The part that jumped out the most at me is your emphasis on how ?members of the media elite disproportionately came from a privileged upper-class background?. Now, if news media, and mass media in general, hold such a large presence in all of our lives, the media that we are going to be exposed to and influenced by, whether we are even conscious of it or not, is all going to be dictated by the individuals behind the media sources, who control the information. The lack of diversity and social standing you added also is a huge issue that obviously distorts the news we see. I think that Youtube is a great jumping off point to try to direct our efforts and sources, and it seems like the natural trajectory of whats popular and what people are watching and paying attention to is following the same idea. Youtube has been blowing up as a more and more valued and reputable source for news media, and I don’t think its importance can be overemphasized in today’s 21st century. The fact that views drive content, and that it is so widely accessible to anyone who has wifi, allows for the content to be more diverse and focus on the issues that are not limited to the “dominant group” or class or race.

Another student commented on our welcome page about the importance of other forms of alternative media like Vine or Snapchat, and I would argue that while these are currently in the introductory stages and are not as reputable as Youtube, they are representative of the new types of media possibilities that exist in the transfer and sharing of information that is so crucial to changing the media and news content of our current popular culture!

You are right, I think we live in a really different world media wise! True, I’m sure many generations have thought that, and each has used their media to perpetuate the ideas they deemed important. For example, right after the printing press was invented one of the first commonly printed things were pamphlets regarding religion. Now, YouTube may not currently have the same reach of traditional media, but with each year it is becoming more and more mainstream to be a avid consumer of Online media. I think that the important aspect in this idea is that it promotes a forum where regular people can discuss events and even criticize the government and the traditional media. Now the dangers with that is that it also easily allows false media to spread like wild fire.

Side note:

In fact thinking about that, I think it should be important to teach children to fact check. Not just on essays and academic work but in life.

I think another important factor regarding the rise of YouTube is the education aspect. More and More aspiring filmmakers and journalists have a place to practice their craft which hopefully will lead to a more diverse work place in the traditional mass media in the future.

Quick comment.

I don’t know much about Vine, but I do know that Snap chat is often used to document events and has even been used to spread awareness during riots etc.

Furthermore, I think we would be silly to discount text based media sites such as Reddit!

http://www.washingtonpost.com/posttv/national/one-night-in-ferguson-told-through-snapchat/2015/03/13/218f38b8-c972-11e4-bea5-b893e7ac3fb3_video.html

Hi team!

I enjoyed Charmaine’s choice of Dowell’s “Aboriginal Diversity On-Screen”. Karmala Todd’s frustration about the abridged interviews was really interesting — having to work with network execs/editors who don’t understand the cultural importance of not interrupting the chiefs. I was also surprised to read that the majority of APTN’s viewers are non-Aboriginal, but this is definitely great news as far as exposure goes.

I instantly thought of a children’s show that I think has only just begun to air on APTN called “Amy’s Mythic Mornings” (http://www.amysmythicmornings.ca/). It’s about a girl and her friends who explore traditional indigenous legends. It airs on Saturday mornings and is available to rent online through Vimeo on Demand. In addition to the TV show, they also have an app for the iOs (from what I can tell, I think it has more to do with exposure of the show itself, rather than teaching about Indigenous stories, though I’m not totally sure). So it’s interesting to see how this particular program is finding ways to work with the new “Internet age”, which is potentially, if not a solution, then at least a helping hand with the changing landscape of streaming shows online and creating interaction in other ways.

I read an article on MONTECRISTO where the creator of the show mentioned that they sometimes adapt legends because: “Some of the stories are not totally appropriate for children, and so they are altered.” What are your guys’ thoughts about that? Maybe that gets into a bigger issue of what’s truly “appropriate” for children, but does that somewhat defeat the purpose of telling these legends, if they’re not being told in their entirety?

(Whoops, I realized I didn’t connect this yet to our team’s research.)

We’re looking at the effect of neoliberalism on Canadian literature, and one of our thoughts is how individual and group voices are heard in the vastness of output of Canadian media. So part of what interested me about Todd’s comment about the abridged interviews is keeping the integrity and the culture of the chiefs’ in tact while still making it an easily digestible source of entertainment/education for the mass audience. Thanks!

Hey there again!

Your team selected a very interesting topic, and is quite relevant with ours. First of all, I want to ask you, what you mean with “easy to digest”. I believe I understand, but I must also add that many aspects in the media are not easy to digest, watch or listen to (ie. The sad and depressing news events, reality TV shows, political debates, gory war movies, rape scenes in movies and shows, even famous zombie movies where violence occurs so frequently, the list goes on)…but they are all under constant streaming, and portray huge messages and influence the masses. Does easy to digest equate to being entertaining, and easily engaging?

Hi Whitney! To answer your question about the appropriateness of reciting the true facts of legends for children, I do not necessarily agree with the idea of sugar coating stories to make them more happily-ever-after. I suppose for the sake of the children, it makes sense to twist the plotlines of these stories. We have to draw the line somewhere, right? I mean, Disney did it with all their movies. Take almost any of the Disney princesses’ stories, and lift the veil to uncover that their original stories were gruesome and not so happily-ever-after fables! Or take Canadian history for instance, from not even that long ago, to discover our own gruesome past with European settlers and First Nation’s peoples in Canada. I find it ironic that the show denies the true ending of a mystical legend, and Canadian history was almost in denial for many years of our true past (with the lack of education about residential schools and assimilation in curriculums)…and these were not even mystical legends.

It would be interesting to have kept the legends as they were on “Amy’s mythic mornings”, for the purpose of educating the masses, but children’s stories do have their PG factors that come into play, especially in the media. However, there were cartoons for children that were aired on television that did not all have happily-ever-after endings. From the years of 1999-2004, a cartoon called Redwall aired on Teletoon, in Camada. The show was a cartoon depicting mise and other animals as warriors. In this TV show for children, there were prisoners of war, deaths, kidnapping, murders, and a lot of dramatic events. The show sounds intense, but it was actually quite entertaining, and played on Saturdays. Shows like Pokemon also had some dramatic fighting events, too, in every episode, for that matter. Or even Coyote always creating traps with bombs to attempt to catch Road Runner. What kind of message does that give to the kids? And what would it matter if the stories on “Amy’s mythic mornings”, were told they way they actually were? Our nations is not going to come to an end or anything like that…parents and people will just complain that these shows are not “child friendly enough”.

If we want a nation that connects with First Nation’s stories and history, we need not tweak these cultural legends into North American friendly versions. If we want to diversify our media, educate our youth, then I believe it would be a great idea to state a story as is. Kids all grow into adults anyways, and pacifying truths is always confusing to children who grow up in a bubble, especially when reality hits. Media is a fine way of getting messages across to the masses, especially in this day in age. So I do agree with you, changing the plot line does defeat the purpose to telling these legends.

Thanks for your reply!

Regarding being easy to digest, I meant more for entertainment and accessibly understandable, rather than violence. I was thinking specifically with the abridged interview. Maybe the better phrase would’ve been “consume” rather than “digest”!

That’s a really good point about the “Redwall” series. I remember watching that when I was younger, and while I do remember the violence I can’t say it was really traumatic for me. Then again, (this might be too tangential of a point) I also remember watching the 1978 animated film version of Watership Down and being terrified of its violence and gore (although that version arguably isn’t intended for children). However, like we’ve said, when the intent is to educate the greater population, it’s probably important to keep as many details as accurate as possible.

That being said, that begins to touch on the fluidity of oral storytelling. One film/animated version is not the “be all, end all” on that particular story. Maybe adaptations, as long we they retain the “message” or intended mood of the story, can still be considered a success?

Interesting topic on age-appropriateness. I think it really depends on the age group. 10 year olds are miles ahead of 6 year olds when it comes to kids. I think Amy’s is more of a kindergarten-level show while Redwall (which I absolutely loved as a kid) is more of a pre-teen show. It’d be appropriate, I think, to have kids be “exposed” to slightly sugar-coated versions of the stories when they’re little, then understand more and more the context as they got older.

Hey Whitney! Thanks for stopping by. Small world, I’ve actually met the producer of Amy’s Mythic Mornings. I love how that show is somewhat like an Aboriginal version of the French-Canadian Caillou. It’s highly accessible to kids of all cultures, and has some neat moral lessons. Kind of reminds me of Sagwa the Chinese Siamese Cat, which was also a kids cartoon but told from the perspective of cats living in a Chinese palace. One thing kids do that adults seem to have forgotten how is that they don’t discriminate. All cartoons are cool. There’s definitely a potential at work here.

Hi again! This time I’m looking at James’s post featuring Hackett’s article.

Examining mass media’s role in shaping Canada is something of great interest to me and my team. The way in which Alternate Media is growing is really fascinating to watch. James linked some good examples, and there are so many more outlets, such as blogs and podcasts. It’s especially important to consider other routes when, as Hackett says “members of the media elite disproportionately came from a privileged upper-class background”. There must be new ways for other voices to be heard, if they cannot buy their way into being the loudest voice.

This is going to sound like the biggest general/sweeping statement ever, but the Internet has been a great way to create communities that share a common voice. Some are buried deep within subreddits, but others have become prominent in making sure the voice of someone other than the “rich, old, white man” is heard. This is especially important when it comes to keeping the younger generation informed. Part of the challenge, I think, is to find a way to make the information accessible and easy enough to digest — the topics are certainly interesting on their own! I’ve found Mic.com really interesting to watch that way. As with all information sources, I think it’s important to keep a critical and questioning mind when reading how the stories are presented, but it’s great to hear an alternative source!

Hey Team,

There is certainly a long history in North America promoting outdated stereotypes of Indigenous peoples for profit. Certainly, the story Freda pointed out of the Adam Sandler movie was a rather despicable modern example; it is assuredly capitalism (as opposed to true creativity) that drives many of his ventures, making him the most overpaid actor (according to Forbes).

Something you guys may be interested in is a project that MTV has started with several young Indigenous artists through Canada & the US. It’s called Rebel Music and it’s a documentary series that focuses on using music as a form of social rebellion. Native America is a specific episode about several young Indigenous (hip-hop/pop/rap) musicians and their fight for social justice & awareness to the conflicts for Native Americans.

Here are these young artists using their music as a platform to talk about the destruction of their land (with proposed pipelines), the missing indigenous women, as well as the challenges of living on/leaving reservations. It is certainly a good start to creating an informative platform from which people can speak.

However, I don’t know how many people have heard about it… Thoughts? Are programs like this stepping in the right direction or do we need an increase of fiction from the Indigenous community to make actual change (by only having documentaries is this only a “real” issue and not one we can escape into)?

-Jamie.

It’s like you guys are reading my mind. I was just in Winnipeg two days ago as I head back to Vancouver by train and I find it hard to believe that Winnipeg is the most racist city in the nation. How are they able to measure that? Is there such a thing as a racist-o-meter? We also have to look at how useful or harmful such labels can be, and how a simplistic title might obscure the complex backdrop of historical events that contribute to the phenomenon we choose to focus our attention. In the case of Winnipeg, its racial problems come from poor federal policies and broken promises that prevent reconciliation from happening. Calling a city racist implies that the population is accountable, but we should really shift the dialogue to how the federal government has failed the city and contributed to its pandemic racial disparity. While residents have communicated to me that they have experienced racism, some confrontations even resulting in physical altercation, I believe that the people themselves are not ignorant and do not wish to exacerbate the situation. In fact, Winnipeg hosts the longest running and largest multicultural festival in the worldand taking part in it reminds me of the city’s commitment to seek closer ties between its various ethnic groups. I am therefore critical of Maclean’s portrayal of Winnipeg as a backwards city without providing a broader scope of the efforts being made to strengthen a sense of community, and I definitely agree that alternative media and public nationwide conversation about these challenges will steer us into more informed solutions

.

Hi guys!

We’re doing our intervention regarding the effects of neoliberalism on Canada’s literature, suppressing as It progresses the amount of “Canadianess” – it’s identity, nationality, and overall culture when marketed through a rising financially ruled system. The concerns are that, in order to spread the production of Canadian literatures, its educational value and culture gets stripped away in order to be more “appropriate” for consumers needs, and in the end, what will happen to Canada’s literature in such a predicament.

Fitsgerald’s article, “‘Evolutionary ,stages of Minorities in the Mass Media’,” heavily ties in on how I view our approach to intervention. As Hayden commented on our page, Canada is seen as a minority compared to that of American culture, whose production and sales are equated much higher in comparison to Canada’s culture. And research shows that a big part of the reason is engrossed in Canada’s work which laced with its background and history, telling of stories about Canada and its culture, while America produces YA novels that captures the interest of its equally young teens (this is just one broad example). Which ties in with the second stage, “Certain minority characters are portrayed as stupid, silly, lazy, irrational, or simply laughable.”

I’m just going to leave a quote from an article we have on our annotated bibliography regarding this from The Future of Canadian Letters, “We do think it important to comment on the efforts of those literary groups belonging to various schools of thought which strive to defend Canadian literature against the deluge of the less worthy American publications. These, we are told, threaten our national values, corrupt our literary taste and endanger the livelihood of our writers.”

So in your intervention, you guys specifically have Aboriginals representation on the mass media, while we have Canadian literature as a whole in our neoliberal state, it’s such a great insight in showing both Canadian stances being ignored or stripped to the side in the world, “A given minority group is not acknowledged by the dominant media to even exist.”

While neoliberalism plays a huge role, so does the government in their fight to keep the value of Canada’s culture alive and intact in its publication of literature, basically protecting it from the corruption of consumerism and away from the influence of American culture (again, back to quote above). But while the government voices their protection and concern, so does their hypocrisy (http://www.dailynews.lk/?q=features/canadas-hypocrisy-human-rights-and-commonwealth-funding), and we know how in one turn, the government can sold Canada’s nation (property, etc) when faced with the promise of a rich market coming into the country. So again, Canada and First Nations (whose properties and culture get bulldozed for the sake of commercialization) get set aside.

Canada and its people, culture and identity should be valued and certainly not “portrayed no differently than that any other group…also not appear extraordinary.” And while we are not take a stance against or for neoliberalism and the federal government) when it comes to the future of Canadian literature (which is the main focus of our intervention), it is clear that these steps are being taken, and no sooner than later Canada and its people are being pushed aside and unprioritized, leaving its rich culture and nation under appreciated and worse, shut down.

Hopefully I didn’t ramble too much and made sense with bringing together our two interventions. I really enjoyed this article, great job guys!

Back for my second comment! This time in regards to the article by Gallagher-Mackay Kelly, Annie Kidder, and Suzanne Methot. “FIRST NATIONS, MÉTIS, AND INUIT EDUCATION: Overcoming gaps in provincially funded schools”. Our intervention from Herb Wyile also tackles the issue of Canadian education from the way neoliberalism has a role in reshaping it. Similar to the problems tackled in the article by the First Nations, Canada suffers a parallel fate when neoliberalism pushes the culture embedded in Canadian curriculum (its background, history) “towards a commodified, even privatized model of education” that is feared will dampen the very “Canadianness” being taught and changed to fit what is commercialized. Currently First Nations aren’t represented in the media and in the curriculum of Canadian education system. Which is absurd, given that many of Canada’s culture derives from the First Nations who has greatly shaped it, and continues to do so. Besides social studies (and even within that course it is barely addressed) First Nations, Metis and Inuit history is not taught. And many of us live through high school and beyond without the knowledge of what First Nations and its people contributed or who they even are (case in point: me). And similarly to the effects of a growing privatized system thanks to neoliberalism, many of Canada’s literature will result in “the erosion of funding for the social sciences and humanities; and the increasing reliance on the private sector for educational funding, with all its attendant compromises.” So more and more of these histories and background of Canada, its people and its culture will be subtracted from the curriculum, moreso than it already is now. So truly the question is, what would become of Canada’s literature in the future? What would become of the First Nations, Metis and Inuit education?

It’s interesting to find this common bond in our intervention (again), but this one more strongly so in that education is universal around Canada, and many forces are showing its affects in changing it, unfortunately so, but now it will bring awareness on what must be done to stop and save the future of Canada’s education system to include its history and people more into its curriculum and to the minds of students.

You have such a focused topic, and that makes for great depth.

I was just going to add this to our annotated bibliography discussing multiculturalism, but may as well post it here first: http://web.b.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=755ab31e-7bdc-4a7a-a982-233cd01f3c95%40sessionmgr198&vid=1&hid=116

That is a really great essay on Multicultural Young Adult Literature as a Form of Counter-Storytelling. As Hughes-Hassel says:

“We cannot overestimate the power of seeing (or not seeing) oneself in literature. Culturally relevant literature allows teens to establish personal connections with characters, increasing the likelihood that reading will become an appealing activity. It helps them identify with their own culture, and it engenders an appreciation for the diversity that occurs both within and across racial and cultural groups… multicultural literature can act as a counter-story to the dominant narrative about people of color and indigenous peoples” (Hughes-Hassel 214).

As Chimamanda Adichie points out in her famous TEDtalk, stereotypes are not necessarily wrong, but only make up a “single story” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D9Ihs241zeg). Therefore, they lead to great misunderstanding, and a need for new perspectives. On one hand, minority groups should not be inserted into a story to be a ‘token x character.’ On the other hand, children should not read a story and have to ask, “Why are they always white?” (Larrick 84). With the turn of a page, whether a book or a smartphone, one should expect to see a new perspective representative of the vast diversity of cultures, ethnicities, and opinions. Simply including different cultures in a story, whatever medium, can go a long way in encouraging young minority members to learn without the pressure of stereotype threat.

I would like to speak about Angela Olivares’ comment about protecting our literature against the influence from America. I find the quote about protecting Canada from “the deluge of less worthy American publication” to be rather heavy handed. What we have to realize is that a democratic society like Canada entails that its citizen has full autonomy to consume the media of their choosing. Based on the stats given from my friend (and I know this is in no way scholarly haha), but 80% of the content consumed in the media by Canadians are American, because American content resonant not only with their northern neighbours, but they transcend linguistic barriers and have influence far beyond the anglophone world.

My critique of making a conscious effort to defend Canadian literature is that Canada hasn’t even emerged with a consensus on what constitutes Canadian culture. Any utterance of something that is Canadian implies that its opposite is un-Canadian, and while it may make sense to the majority it may insinuate the exclusion of the minority. To give you a less politically charged example, my friends in Alberta or Ontario or Quebec might say that Canadian winters are the essence of the Canadian-ness (might I reference Gilles Vigneault’s “Mon pays, c’est n’est pas un pays, c’est l’hiver.” which translates roughly to “My country, it is not a country, it is the winter”). Does this expression of Canadian-ness inevitably silence the experience of Vancouverites who do not experience sub-zero temperatures and heavy snowfall for half of the year? Is it possible to give voice to what one believes to symbolize Canada while at the same time being inclusive to the experiences of other Canadians? I believe that excluding American influences is, in a way, an act of silencing.