History, Background & Language

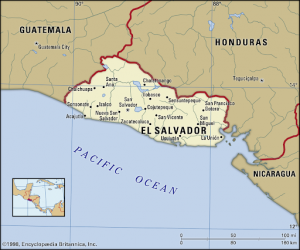

El Salvador

El Salvador is a country located in Central-America and it is the only country in the area without Caribbean coast. It is the smallest country in the region, yet the most densely populated with approximately 6,702,000 inhabitants (Varela and Browning). El Salvador was originally the land of many Indigenous groups, in particular the Pipil, which bears resemblance to the Aztecs of Mexico. The first contact with the Spanish was in 1525, and it wasn’t until 1821 that along with the other Central American provinces, El Salvador became independent from Spain (“A Guide to the United States’”). The official language of the country is Spanish, yet there were many languages and dialects spoken by Indigenous groups before colonization, specifically Nahuatl. As of today, El Salvador is a Mestizo country with 90% of the population being a mix between Indigenous and European descent and 50% of the population practicing Roman Catholicism.

Pipiles

There are various Pipil groups all around Central America. For the purposes of this lecture, we will focus on those native to El Salvador, specifically those in Izalco and Cusatlán which can be referred to as the Nahuatl Pipiles or just Pipiles.

The Pipiles are the predominant Indigenous group of El Salvador. They are said to have migrated from Mexico to Central America in the 11th century to flee from the droughts and social and political unrest (Fowler) and are descendants of the Aztecs, making Nahuatl their native language. Nahuatl is the most important of the Uto-Aztecan languages because of its large number of speakers and was the language of the Aztec and Toltec peoples of Mexico (“Nahuatl language”).

Religion

Aztec influence on Pipil culture is especially evident in Pipil belief systems and spiritual practices (Fowler). The Pipiles worshiped many gods very similar to those of the Aztec, in particular, Tlaloc (the Rain God), Quetzalcoatl (the Feathered Serpent), Mictlanteuctli (the God of Death), and Xipe Totec (the God of New Spring). They worshipped these gods following their sacred calendar of 260 days which is related to the solar calendar of 365 days and the Mesoamerican ritual cycle of 52 years commonly known as the “Mayan Calendar”.

The Conquest

During the conquests by the Spanish, the Pipil peoples resisted and defeated Spaniard Pedro de Alvaro in the Battle of Acajutla in June of 1524 (Fowler, William R., and Jeb J. Card). In 1528, the Spanish returned, and with the help of Indigenous allies in what is now Mexico and the command of Diego de Alvarado, the Pipiles were defeated. The Pipil capital of Cuscatlán was conquered and became the town of San Salvador.

Colonialism

Following the conquest, Pipiles became part of the Spanish system (Fowler). This forced Pipiles to produce wealth for the Spanish, yet, contrary to Spanish desires, El Salvador did not have any precious metals, making agriculture the only source of wealth for the Spanish to exploit in the region.

Similarly to the Shipibo-Conibo people, a system of encomiendas was set in place by the Spanish. The Spanish Crown claimed the land of the Nahuatl Pipil peoples and gave it to Spanish inhabitants who were representatives of the crown (Haggarty). These Spaniards received encomiendas (assignments) from the crown, which they had to complete in order to keep their land and pension from the Crown. The encomienda system gave the Spanish inhabitants permission to enslave all the Indigenous people living in that land. Male Pipiles were forced to cultivate certain crops, build, mine, and other types of manual labor. Women slave duties were cooking, cleaning, child-rearing, and other forms of domestic labour (Fowler and Card 212). It was through the encomiendas—the enslavement of Pipiles—that cacao was produced in El Salvador, which ended up being one of the biggest exports during the 1600’s, since demand for it in Europe was growing.

La Matanza

Assimilation into Spanish colonialism was a tumultuous process for the Pipil peoples, and as a result, there was a surge of revolts that occurred after El Salvador became independent of Spain. The most notable and deadly was in 1932, known as “La Matanza” which translates to “the massacre” (“Jan. 22, 1932: La Matanza (“The Massacre”) Begins in El Salvador”). This revolt was organized by Pipiles and peasants who demanded better working and living conditions following the decision from the government to prevent elected Communist Party members from holding office, as well as to resist further alienation of communal lands (Fowler). In response, under the rule of General Maximiliano Hernández, it was ordered that anyone who appeared Indigenous just by physical appearance should be killed. The Indigenous were especially targeted because Hernández believed this had been solely a Pipil scheme (Fowler). It is estimated that at least 30,000 Pipiles were killed during the revolt.

Pipil Foodways

La Mujer y el Maíz

Like the Aztecs, the staple crops of the Nahuatl Pipiles are maize and beans. Specifically, the elote which is also known as “white corn.” The tropical climate of El Salvador also allows for the cultivation of many types of fruits such as mango, papaya, tamarind, oranges, bananas, watermelon, cucumber, lettuce, tomatoes, and radish (“ El Salvador”).

A pipil folk tale explains how elote came to the possession of the Pipiles, which describes a beautiful woman, the daughter of the Lord of the Pipiles who had big eyes and white teeth. It is believed that one day she came across a god who she fell in love with and they had a child together. Meanwhile, her village experienced a famine due to rats eating all the maize seeds. The beautiful woman felt the pain of her people and decided to plant her beautiful white teeth which resulted in white elote. Ever since then, Pipiles have had abundant elote blanco and thanked the beautiful woman for her sacrifice (“La Mujer y el Maíz en la Tradición Oral”).

There are many other tales that recount the origin of maize, which show the importance of this crop for the Nahuatl Pipil peoples (Schultze-Jena and Martínez 42 ). Maize remains a staple crop for Salvadorans, and many dishes have made maize their star ingredient: tortillas, pupusas, tamales, atol, chicha de maíz (an alcoholic drink), and cafe de maíz (a coffee-like drink) to name a few (Fowler).

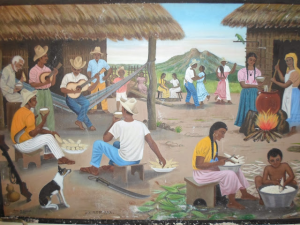

Atolada

Every year, at the end of August when the harvest of maize is over, the festival de maíz—also known as atolada—is celebrated (Hawkins). This festival is a great example of mestizaje, because the tradition arose from the Pipiles’ reverence for corn but now Catholic traditions have been added. During the festival de maíz, there is a parade with floats which show the Virgin Mary at the centre, surrounded by corn (Cubias). Atoladas allow families to come together, thank God for the harvest, attend Mass, and enjoy amazing food—most of which is made from corn. Nowadays, atoladas are mostly celebrated by Salvadorans who own “fincas” (ranches), and depend on milpas for the majority of their food (Hawkins).

Joya de Cerén (Jewel of Cerén) is one of the most important archaeological sites in El Salvador and has been described as the “Pompeii of the new world” because it was buried by ash of a volcanic eruption around 600AD (Amaroli and Dull; Conyers 378). Archaeological studies at Joya de Cerén have demonstrated that yucca was also cultivated in Pipil milpas, as well as how the Pipiles had devised an irrigation system for the milpa.

http://anecdotariodevida.blogspot.com/2017/11/camilo-minero.html

Agriculture During Colonial Times: Cacao & Indigo

In the Nahuatl Pipil tradition, cacao was used in foods, during sacred ceremonies and as the main currency. There is evidence that cacao was being exported from El Salvador to other parts of Mesoamerica before the conquista by the Spanish (Ripton 2). A counting system was even developed specifically to count cacao for trading: a circle meant one, a flag was ten, a feather meant four hundred, and a bag of incense represented eight thousand pods (Sampeck 43). By 1524, when the Spanish colonized the region, this area was one of the biggest cacao producers in the world (Sampeck 40). Since the Pipil’s system of growing cacao was so well developed, the Spanish took advantage of this and produced a significant quantity of cacao in the encomienda system (Fowler). Cacao became a strong currency, and records show this currency was also used by the Spanish conquistadores in Mesoamerica. The word “chocolate” became more popular in Europe and the demand for more cacao increased. Spaniards forced their Pipil slaves to grow cacao for export but soon after, the market became saturated, and there was soil exhaustion and plant disease, which led to the Spaniards no longer exporting Salvadoran cacao (Sampeck 49). This negatively impacted the economy, leading to an economic “bust.” In the 1700, the economy picked up with the export of anil (Fowler and Card 200).

Anil—known as xiquilite in Nahuatl—means “blue herb” and is the dye extracted from a plant that was traditionally used by Pipiles to add colour to ceramics and textiles. Xiquilite powder was also applied to Nahuatl Pipil children’s heads as a remedy for headaches and other ailments (Coreas). The volcanic soil of El Salvador favours the growth of anil, and there are estimates that between the years 1783 and 1792, 91% of anil in Central America was produced in El Salvador. The Spanish authorities forced Pipiles to cultivate and process indigo which was then exported to Europe. The process to extract the dye from the herb was very strenuous, and the working conditions were unsanitary (Jesse). The demand for indigo was so high, that it resulted in staple crops not being cultivated in high enough numbers, and Pipiles became malnourished—consuming 40% less corn than Indigenous people in Mexico (Ripton 13). The Spanish then lost interest in Indigo, because a synthetic dye was discovered in Germany, making Indigo obsolete. Similar to when Pipiles stopped cultivating cacao, once the Spanish lost interest in Salvadoran Indigo, El Salvador experienced another economic “bust.” Following this, coffee was introduced to Mesoamerica from Africa, and it started to be cultivated in El Salvador (Jesse).

Coffee & the Global Market

“If coffee is good, the economy is good” (Paige 14)

After El Salvador gained independence from Spain, wealthy Spanish families still continued to hold the power and controlled the agricultural industry (“History of Coffee in El Salvador”). It was at this time that there was a shift in the purpose of agriculture, where peasants were no longer working to live from their crops, rather they were working to earn a wage (Lindo-Fuentes 117). Coffee plantations gave rise to the class of “coffee elites”—those that owned coffee plantations and got wealthy by exporting the coffee and maintaining low-wage manual labor. Coffee was described as “the backbone to the Salvadoran economy,” and coffee elites controlled multiple aspects of the country’s economy (Paige 10-14). The wealth in domestic banks was from coffee, and it was the coffee families that controlled and owned the banks until 1980. After the civil war in the 1980’s, growing coffee became a good opportunity for those experiencing poverty in rural areas, and in the span of a couple years, 78% of coffee farms in El Salvador were owned by small producers (“History of Coffee in El Salvador”).

Globalization: Nahuatl Pipiles in El Salvador Today

What happened to their foodways?

The Pipiles had long maintained subsistence crops and communal lands, known in Spanish as ejidos. However, in the middle of the 19th century, the coffee became an important export crop for El Salvador. This growing export brought in a lot of new foreigners looking to buy land and get into the coffee business. However, they found that the most fertile land was used by the Pipiles for their subsistence crops of corn, beans, rice and yuca (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 14). The government decided that the Pipil community farming was impeding agricultural growth in the country and ejidos were abolished by law in 1882. This had a severe impact on the Pipil community in El Salvador, as they could no longer grow the crops necessary to sustain their families. The Pipiles protested the law, and in some areas it was not enforced out of fear of being attacked by the Indigenous community. Ultimately, however, many Indigenous peoples still lost their land and instead became nomads or occupied land illegally (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 15). This unrest contributed a great deal to the previously mentioned La Matanza. This was only the beginning of a serious loss of culture for the Pipiles, that extends all the way to today.

Language and Identity

Over time, the Pipiles peoples have lost the external characteristics, such as their traditional clothing and language, that are typically defining traits of an ethnic group (Lemus, “Un Modelo de Revitalización” 26). Following the La Matanza uprising, the Pipil language Nahuatl was considered a dangerous, rebel language, and its use was strictly prohibited (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 15). Speaking the language in some regions was punishable by having the tongue cut off (Moncada, “Pueblos Indígenas de El Salvador” 152). Many Pipil parents are open about the fact that they would rather their children learn English than Nahuatl, as they believe that their native language has only ever brought them persecution (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 17). While Nahuatl had once been the lingua franca of the entire region, by 1982 most of the El Salvador population only spoke Spanish. By the 2000s Spanish had completely replaced Nahuatl for all practical use. The Pipil Indigenous language is now mainly used solely in household situations (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 14). Along with the loss of their language, the Pipiles population numbers have decreased significantly since the Spanish conquest.

It is difficult to identify how globalization has affected the Pipil way of life and food systems, because it seems that the greatest way they have been affected is through a loss of population. Lemus describes a few different factors of the rapidly diminished Pipil population, many of them beginning during colonialism. For one thing, large parts of the population were killed by diseases such as syphilis, measles, varicella and typhoid, which were likely brought to the Indigenous communities by the European settlers (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 13). As well, the working conditions on the cacao plantations were quite poor and led to a lot of young Indigenous deaths. Furthermore, with the lack of laws protecting the Indigenous communities, the Spanish were able to do pretty much whatever they wanted to the Pipiles, without consequence. This made way for a lot of abuse. Finally, Lemus explains that a lack of fences resulted in livestock roaming freely and consequently destroying the Pipil subsistence crops of corn and other vegetables, which harmed their nourishment and ability to survive (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 13). La Matanza was also, of course, an important contributor in dwindling Indigenous population numbers and changing the way Indigenous peoples of El Salvador identify themselves.

The Effects of Mestizaje

In a big way, Salvadoran culture is now widely defined by mestizaje, the racial, cultural and social mixing among different Indigenous peoples and Europeans as a result of actions taken during and following colonialism (DeLugan, “‘Turcos’ and ‘Chinos’” 5; Lemus, “Un Modelo de Revitalización” 26). As the population began to dwindle, the Spanish felt that they had to bring in men from Guatemala (likely from a Pipil city called Escuintla) to marry Pipil women in Izalco and grow bigger families that would then be forced to pay more taxes in the Spanish encomienda system (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 13). This, along with the abuse of Pipil women by the Spanish, increased overall population numbers, but also contributed to the loss of the Pipil identity in that region, and the growth of mestizaje. According to a census taken in 2007, around 86.3% of the county’s population self-identify as Mestizo. This provides a unifying element for most of the country’s population. However, as a result, only 0.2% of the population consider themselves Indigenous (Lemus, “Un Modelo de Revitalización” 26). Many local Indigenous associations and academics believe that this number is much higher, however it is quite difficult to know for sure because of how many Indigenous peoples choose to identify as Mestizo (Lemus, “Un Modelo de Revitalización” 26). This brings into light a very important question. How do we classify mestizaje in comparison to Indigeneity?

Following colonialism and La Matanza, the Pipiles themselves began to resent their Indigenous identity. The Pipiles peoples grew to believe that ladinos, their term for the children of an Indigenous person and a Spaniard, or an Indigenous person who speaks Spanish and no longer considers themselves a part of the Indigenous community, had better lives (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 13-14). They realized that by acting like a ladino and learning to speak Spanish, they had better opportunities and quality of life. Many members of the community who manage to make this transformation never return. If they do, they come back as ladinos and look down on the Indigenous peoples (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 14). This discrimination is quite common throughout El Salvador, while mestizaje is meant to promote the country’s diversity, many still reject the Indigenous peoples and culture (DeLugan, “‘Turcos’ and ‘Chinos’” 5). This is a large contributor as to why the Pipiles are considered the “Invisible Indigenous” of El Salvador, to the point where many citizens believe that Indigenous groups no longer even exist in the country (Lemus, “Un Modelo de Revitalización” 26; Moncada, “Pueblos Indígenas de El Salvador” 144). It was only in June of 2014 that the Indigenous peoples of El Salvador were officially recognized by the government in an amendment of El Salvador’s constitution (DeLugan, “‘Turcos’ and ‘Chinos’” 4). This had been a main goal of several Indigenous communities and activism groups for quite some time.

Pipil Activism Today

For a long time there was only one organization representing the Indigenous peoples of El Salvador, called la Asociación Nacional de Indígenas Salvadoreños (ANIS). However, many new social organizations were formed after the peace agreement was signed in 1992, one of which being el Consejo Coordinador Nacional de Indígenas Salvadoreños (CCNIS) (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 21). This organization is one part of 12 different Indigenous Associations which work together to improve Indigenous rights to land, healthcare and education all across Latin America (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 22). Some more recent initiatives include la Dirección Nacional de Pueblos Indígenas y Diversidad Cultural (the National Directorate of Indigenous Peoples and Cultural Diversity), which has specific subdivisions working to fight for Indigenous rights and coordinate communication between the state and the Indigenous communities. As well, in specific areas there have been regional ordinances which recognize the Indigenous inhabitants of that region and guarantee some rights such as land sovereignty and protection from discrimination (Moncada, “Pueblos Indígenas de El Salvador” 144). However, despite these efforts and others, the Pipiles are still invisible to most of El Salvador and the rest of the world, lacking rights, losing their language and their culture along with it. Lemus describes how some of these organizations are so inefficient because the Indigenous peoples themselves don’t understand their efforts or plans. Many Pipiles don’t approve of the fact that the leaders of these organizations are ladinos and not full community members (Lemus, “El Pueblo Pipil” 22). They feel that these leaders are simply using the Indigenous image for their own political gain.

In closing…

Each member of this group has close ties to Central America, as we’re sure many of you do as well, making this project one near and dear to our hearts. We hope you enjoyed it as much as we did, and that you learnt something new about the Pipiles of El Salvador.

Timuitat tel! (“We’ll see you soon” in Nahuatl).

References

“A Guide to the United States History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: El Salvador.” United States Department of State, https://history.state.gov/countries/el-salvador. Accessed 2 Nov. 2020.

Amaroli, Paul & Dull, Robert. “Milpas Prehispánicas En El Salvador.” Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 1998.

Conyers, Lawrence B. “Archaeological evidence for dating the Loma Caldera eruption, Ceren, El Salvador.” Geoarchaeology, vol. 11, no. 5, October 1996, pp. 377–391.

Coreas, Gerardo. “Historia del anil.” Centro Cultural Salvadoreno Americano. http://elanil-enelsalvador.blogspot.com/2009/11/historia-del-anil.html. Accessed 15 Nov. 2020.

Cubias, Manuel. “El Salvador: tradición, fiesta y hermandad en el Festival del Maíz.” Vatican News. https://www.vaticannews.va/es/iglesia/news/2019-08/el-salvador-tradicion-fiesta-hermandad-festival-maiz.html. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020

DeLugan, Robin M. “‘Turcos’ and ‘Chinos’ in El Salvador: Orientalizing Ethno-Racialization and the Transforming Dynamics of National Belonging.” Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies, 2016, pp. 142-162, dx.doi.org/10.1080/17442222.2016.1164943. Accessed 6 Nov. 2020.

“El Salvador.” Countries and their Culture. https://www.everyculture.com/Cr-Ga/El-Salvador.html#ixzz6eTH1RlxJ. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

Fowler, Bill. “The Pipils of El Salvador.” Teaching Central America, https://www.teachingcentralamerica.org/pipils-el-salvador. Accessed 3 November, 2020.

Fowler, William R., and Jeb J. Card. “Material Encounters and Indigenous Transformations in Early Colonial El Salvador.” Material Encounters and Indigenous Transformations in the Early Colonial Americas: Archaeological Case Studies, edited by Corinne L. Hofman and Floris W.M. Keehnen, vol. 9, Brill, LEIDEN; BOSTON, 2019, pp. 197–220. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctvrxk2gr.15. Accessed 24 Nov. 2020.

Haggarty, Richard A. “Spanish Conquest and Colonization.” Country Study. http://countrystudies.us/el-salvador/4.htm. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

Hawkins, Elizabeth. “In El Salvador, corn harvest brings together families split by migration.” Institute of Current World Affairs. https://www.icwa.org/corn-harvest-brings-together-families-split-by-migration/ . Accessed 10 Nov. 2020.

“History of Coffee in El Salvador.” Equal Exchange- fairly traded. https://equalexchange.coop/history-of-coffee-in-el-salvador. Accessed 23 Nov. 2020.

“Jan. 22, 1932: La Matanza (“The Massacre”) Begins in El Salvador.” Zinn Education Project,https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/la-matanza. Accessed 6 November, 2020.

Jesse, Seth. “Indigo and Indigeneity in El Salvador.” Focus: Native Americans and their Resources, Grassroots Development, Journal of the Inter-American Foundation, 2012.

“La Mujer y el Maíz en la Tradición Oral.” Food and Agriculture Organization,

http://www.fao.org/3/Y3841s/y3841s04.htm. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.

Lemus, Jorge E. “El Pueblo Pipil y Su Lengua.” Cientifica 5, vol. 4, no. 5, 2004, pp. 7-28, www.academia.edu/14264404/El_pueblo_pipil_y_su_lengua. Accessed 6 Nov. 2020.

—. “Un Modelo de Revitalización Lingüística: El Caso del Náhuatl/Pipil de El Salvador.” Wani, vol. 62, 2010, pp. 25-47, www.camjol.info/index.php/WANI/article/view/857. Accessed 5 Nov. 2020.

Lindo-Fuentes, Hector. “Weak Foundations: The Economy of El Salvador in the Nineteenth Century 1821-1898.” Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3199n7r3/. Accessed 21 Nov. 2020.

Moncada, Mariella H. “Pueblos Indígenas de El Salvador: La Visión de Los Invisibles.” Centroamérica Patrimonio Vivo, vol. 2, edited by Fernando Quiles and Karina Mejia, Acer-VOS, 2016, pp. 138-157, rio.upo.es/xmlui/handle/10433/4997. Accessed 6 Nov. 2020.

“Nahuatl Language.” Britannica, 22 Mar. 2016, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nahuatl-language. Accessed 6 November, 2020.

Paige, Jeffery M. “Coffee and Power in El Salvador.” Latin American Research Review, vol. 28, no. 3, 1993, pp. 7–40. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2503609 . Accessed 24 Nov. 2020.

Ripton, John Robert, “Export Agriculture and Social Crisis: El Salvador to 1972.” Columbia University, pp. 2-30, 1997.

Sampeck, Kathryn. “El paisaje cultural del chocolate: pipiles izalcos y cambios semánticos en el mundo atlántico.” La Universidad, 2013-2014.

Schultze-Jena, Leonard & Rafael-Lara Martínez. “Mitos en la lengua materna de los Pipiles de Izalco en El Salvador.” Editorial Universidad don Bosco, Vol, 9, pp 39-59, 2009.

Varela, Rene Santamaria, and David G. Browning. “El Salvador.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 20 May 2020, https://www.britannica.com/place/El-Salvador. Accessed 6 November, 2020.

Dennis Avalos Ponce

October 23, 2021 — 1:00 AM

It’s very sad to see how inaccurate this page is and how it is filled with racist biases like the term Pipil to start. The language they speak was nahaut not Nahuatl. It’s a large enough variation from Nahuatl to not count as a fielect but an individual language. Pipil is a Nahuatl term meaning child that was given to the nahua indigenous people of el salvador because indigenous groups from Mexico thought their language was a child like versión of their own. The list goes on…

Fausto

October 11, 2023 — 10:37 AM

This is so helpful