IN LABOUR: The Impact of the Pandemic on Working Mothers

Click here to view our project

Objective

In this project, our aim is to tell the story of working mothers aged 25-44 during January 2021 to September 2022 and to connect our findings with the myriad studies (Andrada-Poa et al., 2022; Fuller & Qian, 2021; Turner et al., 2022; Zanhour & Sumpter, 2022) conducted on the experiences of working mothers that were documented in the earlier days of the pandemic, when more restrictions and nationwide uncertainty prevailed. We further contextualize the reasons for these changes in employment with respect to significant economic dimensions of this period, including inflation, the rollback of public health measures, and the volatile nature of the post-pandemic work environment.

Our goals for this project are twofold: first, to validate the hardships and tell the story of what working mothers experienced during the pandemic, and second, to reach policy makers considering the stratified nature of the post-pandemic labour economy. We articulate the patterns of change in the employment of Canadian working mothers while demonstrating the economic changes that occurred during this period.

Our static infographics are necessary to supplement our analysis and provide insight into changes in the provincial and national economy during the time the labour force surveys were conducted. A combination of static and interactive visualizations will help the viewer understand some of the forces behind Canada’s economic volatility between January 2021 and September 2022, while allowing them to see how this is reflected in LFS data from that time.

Data

Our primary data sources for our visualizations include the Canadian Labour Force Survey (LFS), the Consumer Price Index (CPI) for Canada, and various other inflation and pandemic-related secondary source and journal articles. The Canadian LFS has been collected monthly since 1945. If requested, it is mandatory for Canadians to respond to the survey.

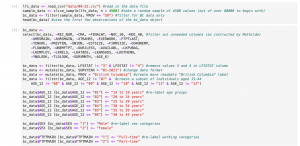

Each LFS dataset contains variables including, but not limited to, responder demographic, labour force status, types of labour, length of employment, and so on. One of the first steps for cleaning our data was to decide specifically which variables to omit from consideration, and which to include. We ended up using over 20 individual LFS datasets, each of which originally containing ~80,00 rows of data

We decided to narrow down the focus of our project to mothers within British Columbia, rather than all of Canada. After conducting random sampling on each dataset, we ended up with ~3400 rows of data to work with

Additionally, we needed to analyze the consistency between variables for each monthly survey, and account for discrepancies or gaps in the type of data gathered each month. Renaming the variables was also required, as many of them were acronyms for technical terms.

Additionally, we needed to analyze the consistency between variables for each monthly survey, and account for discrepancies or gaps in the type of data gathered each month. Renaming the variables was also required, as many of them were acronyms for technical terms.

We used the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to supplement what our LFS data revealed. The dramatic rise of inflation in the last 18 months in Canada is directly intertwined with employment, and we felt that there may be overlap in the trends occurring to the labour economy, and cost of living for Canadians.

Aside from the CPI and LFS, most of our other sources needed to be more qualitative, to help contextualize our topic and relate it more directly to the viewer.

Tools

R: Faced with an overwhelming volume of data (with 21 datasets to clean and merge from January 2021 to September 2022), our team struggled to perform our cleaning procedures in Microsoft Excel, as originally planned, as the software and the limitations of our personal computers created obstacles for working with such large datasets. Instead, we turned to the R Statistical software where we wrote a script to automate the data cleaning processes. A crucial step in our R cleaning process was running a simple random sample on our dataset to decrease our data observations to a more manageable level, while still maintaining the integrity of the dataset.

Tableau Prep Builder: We used Tableau Prep Builder for importing our master dataset, and making some final adjustments before we could create our visualizations. All of our variable names needed to be changed from acronyms into more interpretable names. Certain data types weren’t imported correctly into Tableau from the .csv file, and needed to be manually changed.

Tableau Desktop: This was used to create our main visualizations. It took some time to figure out the most effective way to represent our data, and which filters to include. Our primary visualizations appear as follows:

Wix: We felt that Wix was the most appropriate platform for hosting our project. It gave us the ability to easily integrate our visualizations, and efficiently re-organize and format the layout of text and other images. The end result is a visually clean and easily accessible website which required no coding to create.

Analytic Steps

Starting from scratch, we chose this subject as it was one with a lot of recent data. We started by selecting and analysing the data and variables we wanted to work with. While our objective remained the same throughout the process of our research, the largest obstacle was properly choosing and cleaning our datasets. Even though we had no issue finding the appropriate datasets to analyse, each dataset contained a substantial amount of irrelevant information (such as information or attributes that had nothing to do with working mothers), which needed to be manually removed.

Our initial plan was to analyze monthly datasets across a period of 21 months for all of Canada, but this proved to be unrealistic considering the size of each dataset. We ended up reducing the analysis to British Columbia, from January 2021 to September 2022 and using R to clean the data and conduct random sampling.

Design Process

Our storyboarding process was slow getting started, as we spent a considerable amount of time strictly working to clean our data. As soon as we had the ability to start creating visualizations, we realized how many directions we could go with our narrative, and found it difficult to settle on the scope of our analysis.

Our secondary sources provided strong insight into the understandably shaky labour force in Canada, while also highlighting the unique difficulties that inflation creates for mothers compared to other demographics.

Once we began understanding how inflation impacts women more than men, we realized the need to include data about fathers in our visualization.

Our visualizations emphasize how fathers in B.C., on average, work more hours per week than mothers. We included a filter for age-groups to show the variation between younger and older parents.

Pros and Cons

The most critical aspect of our project was the time period we analyzed. Although there is sufficient LFS data from before and during the pandemic, the datasets are difficult to work with due to their size.

An alternative approach, this analysis could have been conducted using quarterly datasets from each year, starting well before 2020, and ending as close to the current date as possible. This would have been a more comprehensive approach, which would have provided stronger context for the severity of the current economic crisis, and how dramatically the pandemic has affected the labour market.

Additionally, we recognized after creating our visualizations that certain age-groups may have been underrepresented in our datasets. We could have omitted the youngest age group (20-24), and included a few older age groups (above age 44). While we know there are many 20-24 year olds who fit the criteria for our analysis, it seems that there are significantly more on the older end of the spectrum.

Despite these areas which could be improved, the results of our analysis are thought-provoking, and create other questions for future research.

Citations

Andrada-Poa, M. R. J., Jabal, R. F., & Cleofas, J. V. (2022). Single mothering during the COVID-19 pandemic: A remote photovoice project among Filipino single mothers working from home. Community, Work & Family, 25(2), 260–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2021.2006608

Canadian COVID-19 Intervention Timeline | CIHI. (n.d.). Retrieved October 19, 2022, from https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadian-covid-19-intervention-timeline

Consumer price index (CPI) – province of british columbia. (2022, November 16). Retrieved December 1, 2022, from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/data/statistics/economy/consumer-price-index

Fuller, S., & Qian, Y. (2021). Covid-19 and The Gender Gap in Employment Among Parents of Young Children in Canada. Gender & Society, 35(2), 206–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912432211001287

Heer, J. & Shneiderman, B. (2012). Interactive Dynamics for Visual Analysis: A Taxonomy of Tools that Support the Fluent and Flexible Use of Visualizations. Queue, 10(2), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1145/2133416.2146416

Inflation affects women more than men. civil society can help. World Economic Forum. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2022, from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/10/inflation-crisis-hits-women-harder/

Labour Market: Definitions, Graphs and Data. (n.d.). Bank of Canada. https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/indicators/capacity-and-inflation-pressures/labour-market-definitions/

Lemieux et al. (2020) Impact of Covid on Labour Market Lemieux et al. 2020 Impact of Covid on Labour Market.pdf

Munzner, T. (2015). Why: Task Abstraction. Visualization analysis and design (43-65). CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.1201/b17511

The Daily — Labour Force Survey, August 2021. (n.d.). https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210910/dq210910a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2022). Mean age of mother at time of delivery (live births) [Dataset] https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310041701&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2015&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2021&referencePeriods=20150101%2C20210101

Statistics Canada. (2022). Labour Force Survey: Public Use Microdata File. [Dataset]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/71m0001x/71m0001x2021001-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2022). Consumer Price Index (CPI) statistics, measures of core inflation and other related statistics.[Dataset]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810025601&cubeTimeFrame.startMonth=01&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2021&cubeTimeFrame.endMonth=09&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2022&referencePeriods=20210101%2C20220901

Turner, L. H., Ekachai, D., & Slattery, K. (2022). How Working Mothers Juggle Jobs and Family during COVID-19: Communicating Pathways to Resilience. Journal of Family Communication, 22(2), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2022.2058510

Zanhour, M., & Sumpter, D. M. (2022). The entrenchment of the ideal worker norm during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Evidence from working mothers in the United States. Gender, Work & Organization, gwao.12885. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12885

Hi Stuart, Anneke and, Mathilde,

Thanks for offering such an insightful InfoVis, the topic you chose is indeed a timely and significant one.

Your website is easy to navigate and aesthetically pleasing with contrasting red and white colours like the Canadian flag. The graphs are easy to follow as well. It seems like the raw data you were working with has a lot of attributes with names that are all over the place – you did a great job cleaning them! The comparison of the working hours of mothers and fathers is effective, the viewer can see how unstable it is for working women. You also provided abundant economic context and backed them up using numbers. Thank you for explaining keywords such as Labour Force Participation Rate, it provides a coherent and well-rounded viewing experience.

I also noticed that you pointed out the existence of systemic biases for gender in data collection. Good work!

One suggestion (if I have to write any):

The graph ‘Hours Worked for Male Parents by Age Group” demonstrates a sudden drop in hours of work for (25-29 years) fathers around April 2022, it would be more impressive if you could write a brief sentence and explain why there is a drop. This is definitely a long time after the “circuit breaker” – what happened in April 2022? Were there some massive layoffs in different industries?

Overall, I enjoyed browsing through your InfoVis and your blog. Thanks for tackling such an important issue. I hope this raises more awareness for women in the workforce.

– Chloe Zhang

Hi Stuart, Anneke and, Mathilde,

This is a very important and impactful infovis, and the design choices match the weight of impact on working mothers! I think the format and layout of the infovis is very clear and straightforward to follow, getting straight to the important points that make up your argument. It looks like your datasets were very complex and difficult to clean / analyze, so you all did a great job turning it into an easily-digestible infovis format. Providing reference and context to help your viewers understand the labour economy is also thoughtful and enhances the user experience.

As for improvements, I think it would be great to see some interactive aspects to your infovis to make it more engaging! This may be out of scope and a bit too time-consuming to add in brushing and linking for example, but Wix has different buttons and hover actions that can be used to see different views as a work-around, if you are interested in adding interactivity! You could do a hover box with two screenshots highlighting different datapoints that are significant, and that could be a simple way to add a hover action.

Overall, fantastic job! 🙂

Jennifer Kwok