Link to the Article: Culturally Situated Design Tools: Ethnocomputing from Field Site to Classroom

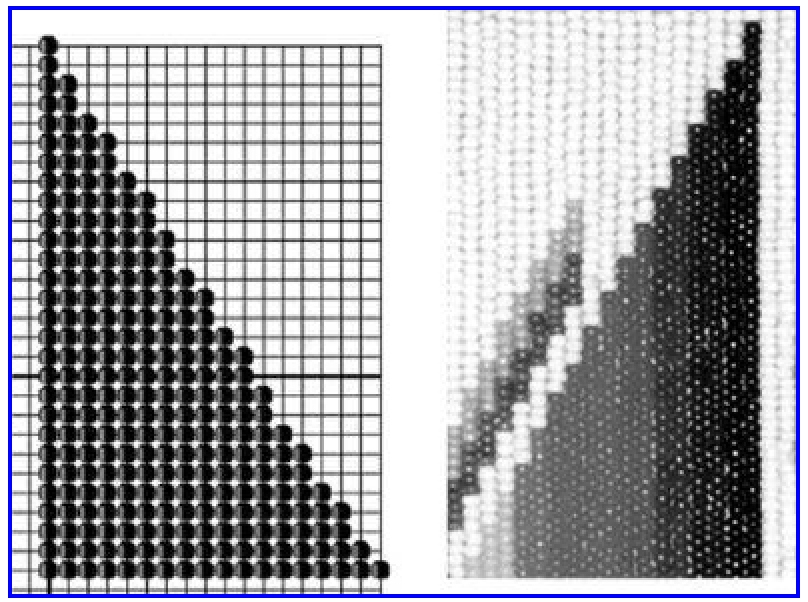

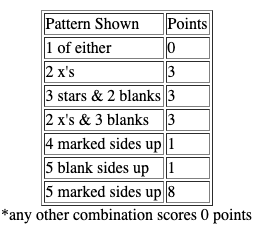

The article is one of the few empirical examples available in literature focusing on the design of culturally responsive computational tools and their impact on broadening the youth’s interest in computing. Eglash et al. (2006) commence their paper by challenging the myth that “we each have a specific culture, and that it is a given, static entity to which our personal identity is fused in a kind of mimetic relationship” (p. 348). They explain that the development of Culturally Situated Design Tools (CSDTs), their culturally responsive ethnocomputing software, is guided by four principles: “deep design themes,” “anti-primitivist representations,” “translation, not just modeling,” and “dynamic rather than static views of culture” (p.348-349). Their Native American design tools include “SimShoBan,” Yupik Navigation, Yupik Parka Patterns, Alaskan Basket Weaver, Navajo Rug Sim, and the Virtual Bead Loom (VBL). The authors describe the latter as a tool that connects contemporary vernacular culture and traditional heritage culture and at the same time it fulfills the curriculum requirements. They described several conflicts in the development process and the application of VBL in the classroom: Firstly, they reported a problem in the original program which was based on a standard “scanning algorithm,” as a result, they developed a second tool based on “Shoshone beadworkers” methods (see figure 1); they kept both designs for the sake of comparison between the approaches. Secondly, when VBL was introduced in Uintah-Ouray Reservation, the Ute group have recommended eliminating the black beads (i.e., regarded as bad luck in the community) from the VBL. As a result, they came up with a color mixer as a solution, which allowed users to create their bead colors. The authors regarded the tensions as “a two-way street, creating new hybrids in both machines and people” (p.356).

|Figure 1: “A comparison of uneven steps in a Virtual Bead Loom triangle (left) and even steps in Shoshone-Bannock beadwork (right).” (p.353)|

Following that, Eglash et al. (2006) reported statistically significant increases in students’ performance on math evaluations and their interests in IT careers. However, the most important outcome of their work was “the trialectic of computer media, math pedagogy, and culture [that] provides a meeting place in which the praxis of social change and the theory of cultural critique can generate new forms of hybridity and synthesis” (p.360).

Reference:

- Eglash, R., Bennett, A., O’donnell, C., Jennings, S., & Cintorino, M. (2006). Culturally situated design tools: Ethnocomputing from field site to classroom. American Anthropologist, 108(2), 347-362. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.2006.108.2.347