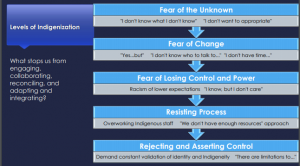

The link above is a PowerPoint presentation from Dianne Binn from Camosun College on Indigenizing Curriculum in post secondary systems. One particular slide drew my attention which was focused on “what stops us from engaging, collaborating, reconciling and adapting and integrating” Indigenous ways of knowing in our classroom.

There will always be reasons to not try something new or be open to new ways of learning. I know I am ready and open to change but many of my colleagues are not. This PowerPoint provides explanations of their fears and ways to approach them. In the slides to follow Binn describes what should be incorporated into our ways of teaching to include Indigenous ways of knowing. She provides a curriculum framework that can be incorporated as a way to Indigenize our pedagogy. Binn explain that some educators turn to learning activities as a way to Indigenize their course, however, “including or adapting learning activities without changing other aspects of the curriculum is not a holistic approach to Indigenization, and in some cases can result in trivializing and misappropriating those activities”. This website will prove useful in my final project as an important description and note that we cannot just change activities in our classrooms. It is a pedological shift in the importance of teaching to the learner as a whole that needs to happen.

There will always be reasons to not try something new or be open to new ways of learning. I know I am ready and open to change but many of my colleagues are not. This PowerPoint provides explanations of their fears and ways to approach them. In the slides to follow Binn describes what should be incorporated into our ways of teaching to include Indigenous ways of knowing. She provides a curriculum framework that can be incorporated as a way to Indigenize our pedagogy. Binn explain that some educators turn to learning activities as a way to Indigenize their course, however, “including or adapting learning activities without changing other aspects of the curriculum is not a holistic approach to Indigenization, and in some cases can result in trivializing and misappropriating those activities”. This website will prove useful in my final project as an important description and note that we cannot just change activities in our classrooms. It is a pedological shift in the importance of teaching to the learner as a whole that needs to happen.