This article provides insights as well as raises important questions pertaining to Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Two of the questions I found particularly interesting are below.

How can we combine the best of modern technology, science, and cultural expression with the guiding wisdom of traditional, Indigenous cultures?

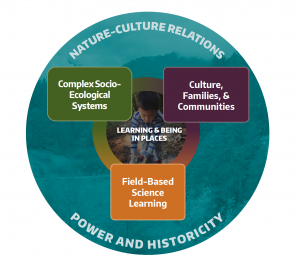

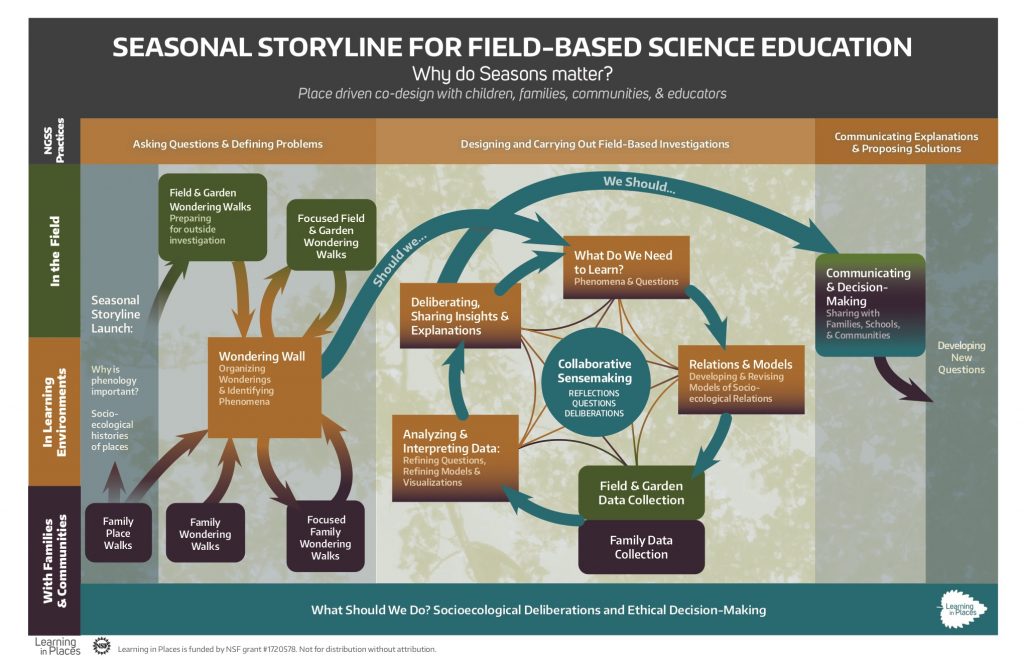

This is a pertinent question that I am asking myself as I work through my research process. As can be seen in the quotes to follow, the importance of place is not only evident to Indigenous cultures and ways of knowing and being, but cultural diversity is related to biological diversity. Relationships with the land are important for the healing of the earth.

We have to learn from both the successes and failures of modern technologies, and we have to pay more attention to the indigenous wisdom of local culture adapted to place. TEK is a place-based knowledge-belief-practice complex of ancient lineage. Locally adapted cultural diversity goes hand in hand with biological diversity. Together they constitute ecocultural diversity. What we are really restoring is our relationship with the places we live in and depend on as we learn, once again, how to be native to these places: to be caregivers to the land; to participate with our elder brothers and sisters, the plants and animals, in the spiritual and physical renewal of the earth and of ourselves.

How can we innovate and transform our culture with one eye on the past (learning from traditional wisdom and practice), and the other on the future (social, ecological, economic, and technological innovation)?

Indigenous human cultures are an expression of generations of co-evolution of humans within the ecosystems they inhabited.

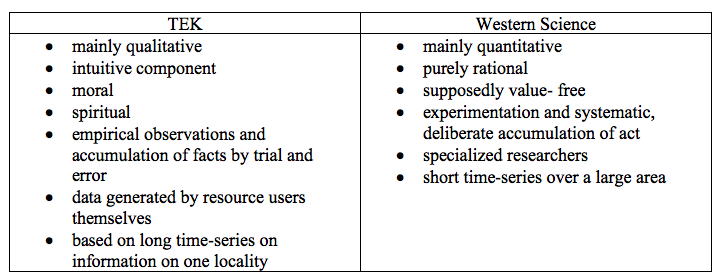

Again, braiding both traditional ecological knowledge and western science can be a necessary relationship for the future prosperity of ecological habitats and to tackle environmental issues such as climate change. It is vital not to dismiss knowledge that has been passed for generations, that is holistic in nature, and not compartmentalized and time-sensitive which is often characteristics of western science.

Cultures that have managed to survive for millennia within their bioregions have a lot to teach us. Over the last few hundred years, we have developed the unfortunate habit of dismissing such knowledge as antiquated and calling such cultures ‘primitive’. Hypnotized by the apparent benefits of scientific and technological progress we made the mistake of dismissing traditional ecological knowledge that underpinned human survival for most of prehistory.

References

Wahl, D.C. (2017, April 23). Valuing traditional ecological knowledge and Indigenous wisdom. Age of Awareness. https://medium.com/age-of-awareness/valuing-traditional-ecological-knowledge-and-indigenous-wisdom-d26ebdd9e141

I found about this book from our colleague Laura Ulrich. Thank you, Laura, for this outstanding resource. Sandoval (2019) presents a three-year research journey in which she worked closely with “Mr. Adams”, a teacher of European-descent, to explore intersections between computer science (CS) and ancestral knowledge across the school and non-school contexts. The introductory chapter introduces a new conception, “Ancestral Computing,” that investigates how to solve complex problems using socio-cultural and historical ecosystem approaches; thus, the connection was grounded in a robust and non-trivial community orientation.

I found about this book from our colleague Laura Ulrich. Thank you, Laura, for this outstanding resource. Sandoval (2019) presents a three-year research journey in which she worked closely with “Mr. Adams”, a teacher of European-descent, to explore intersections between computer science (CS) and ancestral knowledge across the school and non-school contexts. The introductory chapter introduces a new conception, “Ancestral Computing,” that investigates how to solve complex problems using socio-cultural and historical ecosystem approaches; thus, the connection was grounded in a robust and non-trivial community orientation.