This is a presentation at the Indigenous New Media Symposium (2014) by Jarrett Martineau, an award-winning Indigenous media maker, scholar, artist, and storyteller. He is nêhiyaw (Plains Cree) and Dene Sųłiné from Frog Lake First Nation in Alberta, and he is currently based in Vancouver.

He opens the presentation with this quote from Louis Riel (Métis)

“My People will sleep for 100 years, and when they awake, it will be the artists who give them back their spirit.”

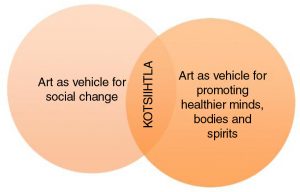

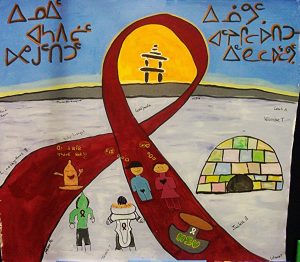

In the presentation, Martineau emphasizes the fundamental components of Indigenous New Media. Building community, asserting strength, and taking back control over self-representation. He also discusses how the pervading background of colonialism, and thus how everything Indigenous artists do is political. “Indigenous media, Indigenous cultural production, Indigenous art, and creativity is always a contestation of [colonialism]” [8:15].

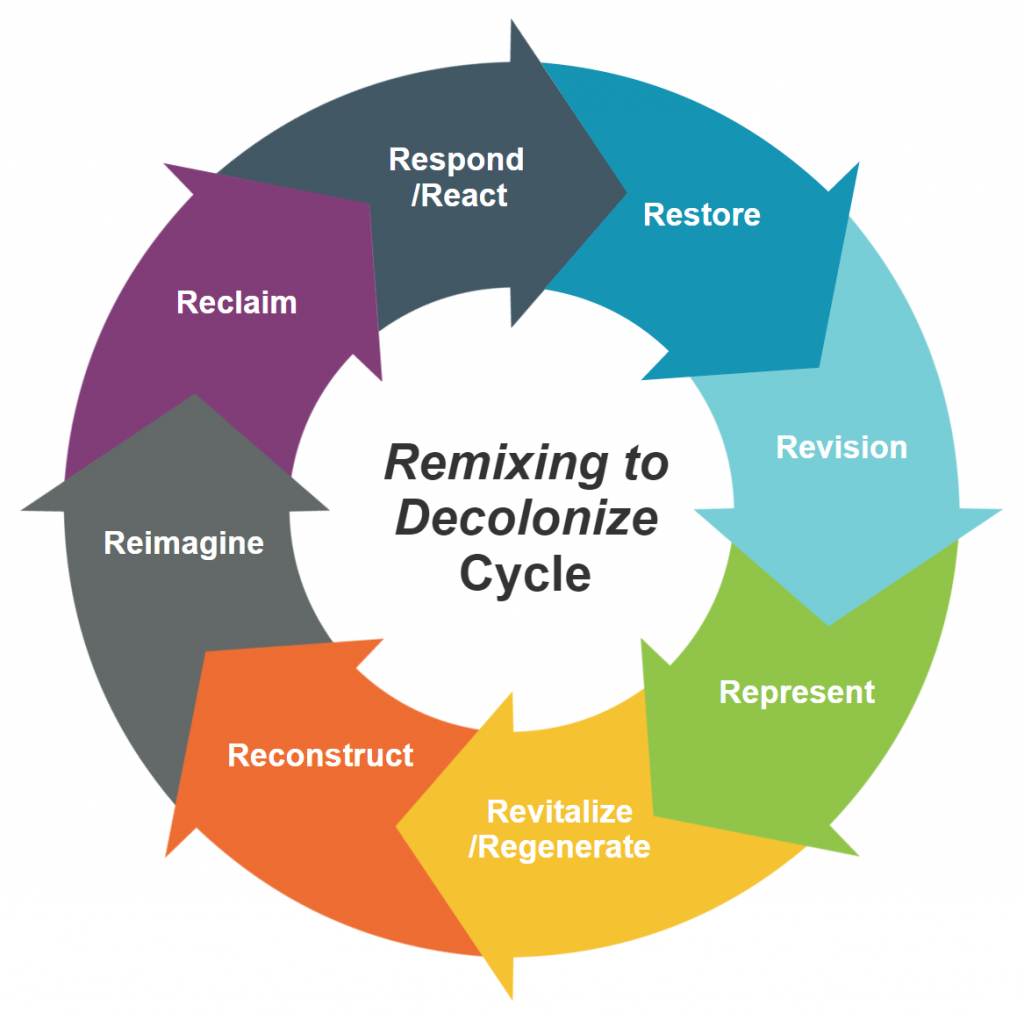

Of particular note is his discussion on the power of Remixed media, as a means of “resistance and asserting resurgence” [10:50]. Remix is reflexive, recombinant, and regenerative. One example he shares is Sonny Assu’s Coke Salish (pictured below). The power of Remix is its power to convey more than aesthetics and to invite conversations.

Martineau’s Decolonize Media project is still online at the time of this posting.