In their paper, Taonsayontenhroseri:ye’ne: the Power of art in Indigenous Research with Youth, Whitlow et al. (2019) report on their arts-based research project, Transformation, Action, Grafitti (#TAG). Participants were from Six Nations, the unceded territory of Brantford, Chili, and the Mapuche territory of Kompu Lof. The project’s goals were first, to nourish cultural pride for Indigenous youth, and second, to educate non-Indigenous youth “through a for-Indigenous-people-by-Indigenous-people framework” (p. 182). During the workshops, participants created doodles based on what they were seeing and hearing. Later, these doodles were collected by the Alapinta (Chilean) muralists, who tied them together into two sister murals. The murals were painted in prominent locations in Six Nations and the Brantford downtown-core. They sparked conversations about reconciliation that, thanks to the Internet and social media, reached globally.

Participants working on the Brantford mural

The authors say this about the power of art:

“For this reason, art was even better medium for communication across the barriers of colonial languages. Haudenosaunee people often struggle to translate their stories from their original languages as English does not communicate the depth and complexity of their own morphology. The images that appear in the mural can be interpreted and valued regardless of spoken language. Indeed, art was the bridge between groups of people who spoke four different languages, often through a translator. Despite our struggles with language, symbolism and cultural imagery became a shared and complex form of communication” (p. 186).

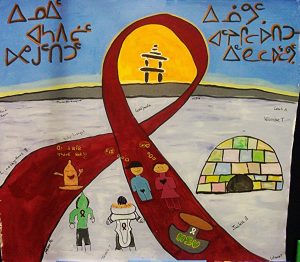

The #TAG’s completed Six Nations mural

Reference:

Whitlow, K. B., Oliver, V., Anderson, K., Brozowski, K., Tschirhart, S., Charles, D., & Ransom, K. (2019). Taonsayontenhroseri:ye’ne: the power of art in Indigenous research with youth. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 15(2), 180–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180119845915