The Climate Investment Funds funded a study showcasing traditional approaches to addressing climate change, helping chart the way forward for integrating these tested approaches, lessons, and experiences into climate action. I think this report is especially useful because it discusses tangible solutions using traditional knowledge and technologies, rooted in local ecosystems, that have shown to be beneficial to ecological preservation.

Some examples of TKT (traditional knowledge and technology) include; traditional housing and architecture, food systems, navigational and resource charts, taro pits, water harvesting techniques, and land extension processes. Broadly, TKT encompasses three elements: knowledge about the environment, knowledge about the use and management of the environment, and values about the environment. The report which is found below, is written specifically for a climate change initiative, however, broadly discusses TKT and its useful applications to other environmental concerns.

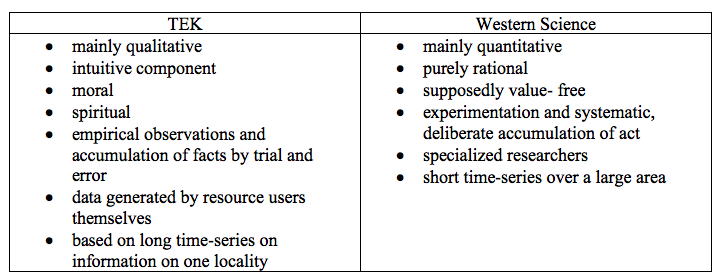

Some differences between Traditional knowledge and Western (conventional) technologies;

• Traditional knowledge systems were developed by trial and error over long periods, while conventional technologies are largely rooted in science and engineering.

• Changes in traditional knowledge are intergenerational in scope as they have evolved slowly, whereas conventional knowledge is generational as it changes rapidly.

• Traditional knowledge is mainly tacit in nature and tends to be relatively localized, while conventional knowledge is more conducive to codification and transmission by modern means, making it universally available.

• In traditional systems, there are no clearly defined innovation systems, whereas conventional innovation systems are more clearly identifiable and defined.

Indigenous ways of managing landscapes have often been framed as the antithesis to progress. But most Indigenous communities hold intimate place-based knowledge, gained across generations, which is an ideal starting point for addressing contemporary challenges such as biodiversity loss, land degradation, and climate change.

Here are seven ways that Indigenous knowledge is translated into vital inventions for conserving and restoring landscapes around the world. In fact, this ancient know-how might just be some of the modern technology we have.

-

Seed-saving methods preserve native plant species in the face of new disease threats

-

Ancient controlled-burning practices ‘fight fire with fire’ to maintain biodiversity and keep humans safe

-

Rotational cropping restores soil, builds biodiversity, and boosts crop yields

-

‘Three Sisters’ intercropping method ups yield and provides balanced diets to gardeners across the globe

-

Traditional drought-resistant planting techniques combat desertification

-

Non-linear conceptions of time help adapt to climate change

-

Ancient drainage canals improve Lima’s water supply

References

Climate Investment Funds, (March 5th, 2020). The contribution of traditional knowledge and technology to climate solutions. https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/knowledge-documents/contribution-traditional-knowledge-and-technology-climate-solutions

Evans, M. (August 7, 2019). 7 Indigenous technologies changing landscapes. Landscape News. https://news.globallandscapesforum.org/37693/7-ways-indigenous-knowledge-is-changing-landscapes/