The STEM teaching tools website has resources, tools, PD modules, news, and newsletters to help teach science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

I was particularly drawn to this website for the resources found under the TOOLS dropdown menu that highlight ways of working on specific issues that come up during STEM teaching called “Practice Briefs”. Each brief highlights the issue, why it matters, things to consider, reflection questions, equity, and actions you can take in an organized, concise, and effective way to easily access. Below are some briefs that I found particularly useful to my research on TEK and STEM.

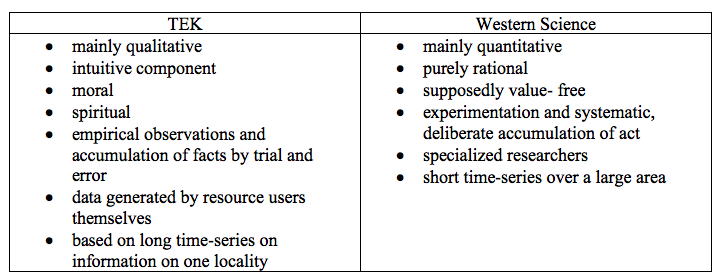

#10 Teaching STEM In Ways that Respect and Build Upon Indigenous Peoples’ Rights: It is vital that educators incorporate Indigenous knowledge and rights into their teaching and lessons.

Teachers should understand and leverage Indigenous students’ ways of knowing and values.

#11 Implementing Meaningful STEM Education with Indigenous Students & Families: Integrating traditional ecological knowledge and western science is important if students are going to connect meaning to experiences.

Teachers should focus on Indigenous ways of knowing & encourage Indigenous students to navigate between Indigenous & Western STEM.

#55 Why it is crucial to make cultural diversity visible in STEM education: Students need to see themselves represented in STEM careers that collaborate and integrate Indigenous knowledge.

Teachers should carefully weave subject matter with activities and images within relevant contexts that validate the contributions of individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds.

#57 How place-based science education strategies can support equity for students, teachers, and communities: Place holds significance to Indigenous ways of knowing and learning. Knowledge rooted in land is at the heart of many Indigenous cultures, this needs to be at the forefront of education.

Teachers should connect science learning experiences in and out of the classroom to students’ sense of place, cultural perspectives, and community assets and issues

References

STEM Teaching Tools. (n.d.). Teaching Tools for Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) Education. http://stemteachingtools.org/