Nil Tekin, Haolin Wu, Michael Wu

Links to Information Visualization Products

- Infographic

Background Information/Context

Obesity is a disease that can be classified as excessive body fat, and may lead to a variety of other health issues (Cleveland Clinic). The causes of obesity are complex, and may be related to genetics, poor mental health, other illnesses, and certain medications (Cleveland Clinic). Repeatedly, high obesity rates have been linked to foods with ingredients that contain high fat, salt, and sugar. There are different types of obesity that are used to classify people by the severity of the illness. Class 1 contains a low risk of obesity, with a BMI between 30 to 34.9, Class 2 is moderate risk with 35 to 39.9, and Class 3 is high risk with 40 or more BMI (MedlinePlus).

In particular, obesity in North and South America is a rapidly growing issue that is affecting the lives of millions around the world. According to Simón Barquera and Juan A. Rivera, this issue has been prevalent in Mexico for the past 30 years, mainly caused by a change in diets due to economic growth, from natural ingredients to more processed ones that have a high fat and sugar content. In Peru, a significant percentage of the population is obese due to unhealthy diets and decreased exercise (Peru Telegraph). In Colombia, economic issues and poor lifestyle choices have led to significant rates as well (Betancourt-Villamizar et al.).

Usually associated with adults, obesity is beginning to affect younger people more than ever. Obesity is an illness that particularly contains not only scientific but psychological layers as well, making it an interesting topic for visualization. We are able to then detect certain trends and connect them to other health conditions and behaviors, such as genetic influences.

Objectives

In this project, our intended goal was to understand the nuances of obesity from three regions: Mexico, Peru, and Colombia, and demonstrate the severity of the illness. With our visualizations, we hope to garner attention onto the illness, to inspire more self-care and healthier lifestyle choices. Our intended audience are adults who are not underweight, as well as older teenagers. Showcasing that obesity is closely related to one’s genetics will hopefully reduce the stigma that exists in society. With our visualization on body weight and exercise, we also wanted to demonstrate that not all obese people are “lazy” and do zero exercise within a week. The rest of our visualizations focused on discovery, including the correlation between age and weight, and eating habits.

Dataset Details

The dataset that we used included information collected from Mexico, Peru, and Colombia. It was very rich with the amount of attributes it contains, which is necessary for such a complex topic as body weight. For example, the age, gender, height, family history of obesity (yes or no), and Body Mass Index (BMI) attributes allow us to get detailed insight into each row that represents an individual. Interestingly, not every row contains data from individuals who are obese, referred to as Normal_Weight, and it includes people classified as just overweight as well, at 2 different levels.

BMI calculation field was created by us when cleaning the data in Excel, and was not originally included within this data source. It was made by dividing their weight in kilograms by the square of their height in metres, based on the metric system.

BMI formula

This calculation was done to allow us to have more freedom to creatively experiment with the attributes on Tableau Desktop.

Tools Used

The main tool that we used to transform our data into an information visualization was Tableau Desktop. As a flexible interface, we could creatively manipulate datasets to convey a story. Selecting certain categories also highlights one and dims others, which allows users to focus on a single aspect at a time, which is helpful when graphs and their marks and colors start to become overwhelming to the eye. The user is also able to select many different types of marks from a list that Tableau provides, which allows for experimentation with visualization preferences.

As for the weaknesses of Tableau, an issue may arise during the creation of calculating fields. If one does not have past experience with coding, they may not be familiar with how formulas work for their visualization. The data must also be carefully cleaned beforehand to avoid errors that the system may not be able to recognize. We had to handle our dataset carefully before proceeding, and plan what attributes we were going to include.

Canva was used as a creative graphic design platform to craft our infographic, containing information about the findings of our visualizations, with the data collected by F.M. Palechor and A.H. Manotas. Images were used in the composition as a tool to catch a viewer’s attention and compliment the findings about obesity.

Analytic Steps

As obesity is a very broad topic, when exploring our dataset on Excel and Tableau Desktop, we initially did not have a distinct idea of what story we wanted to tell with our visualizations. We took some time to think about what arguments we wanted to make. First, our intention was to focus on obesity rates within British Columbia, and found a dataset to provide us with the information. However, it was apparent that drastic levels of obesity trends were not detected within the region, compared to other parts of the world, where it is becoming a more widespread issue even for children. Finally, we found a journal conducted by Fabio Mendoza Palechor and Alexis de la Hoz Manotas, with data that they collected from people within three Latin American countries. Their focus was on two aspects that were associated with causing obesity, eating habits and physical conditions.

With our cleaned data, we had almost 20 attributes, and decided to exclude some of them from our focus, such as the “NObeyesdad” category that placed individuals into different weights. A confusing entry under this was “Insufficient_Weight”: did this mean the person was underweight? The article mentions it as well, and perhaps labeling them as underweight instead may have been a clearer choice, for the reader to understand better.

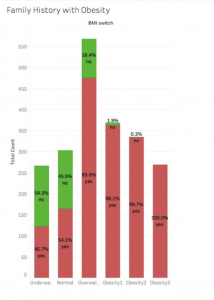

This first report presents a comprehensive analysis of the correlation between obesity and family history, drawn from a study that categorized subjects into six weight classes: underweight, normal, overweight, and obesity classes 1, 2, and 3. The visual representation of data showcases a strong positive correlation between family history and the incidence of obesity, with a higher proportion of subjects with a family history of obesity being found in the higher obesity classes. Among individuals categorized as overweight, 83.6% have a family history of obesity. This percentage rises distinctly with the severity of obesity: 98.1% in Obesity 1, 99.7% in Obesity 2, and 100% in Obesity 3. A significantly lower percentage of individuals with underweight and normal weight report a family history of obesity.

The data visualization showcases the influence of genetics on body weight. The ascending trend of family history prevalence with increasing obesity categories suggests that obesity is not solely a product of lifestyle choices, but rather a complex trait influenced by genetic makeup. There exists a stigma that associates obesity with laziness; however, our findings emphasize that obesity is frequently linked to factors beyond individual control, such as genetics. Recognizing the genetic component in obesity is essential for fostering a more empathetic and scientifically informed public attitude.

In our study, information visualization serves as a crucial tool in uncovering the nuanced relationship between obesity and family history. Interestingly, it also highlights that a substantial proportion of underweight and normal-weight individuals—45.7% and 54.1%, respectively—report a family history of obesity, prompting intriguing questions about the mechanisms of obesity resistance. Despite their genetic predisposition, these individuals do not exhibit obesity, suggesting the presence of other influential factors. This revelation paves the way for subsequent research to delve into the impact of acquired factors such as lifestyle, diet, and physical activity on obesity. The visualization underscores the complex interplay between inherited and environmental contributors to body weight, emphasizing the need for a multifaceted approach to understanding and addressing obesity.

Exploring the relationship between exercise frequency and body weight categories, our graph categorizes subjects as underweight, normal, overweight, and obese. Notably, a lower frequency of exercise is observed among individuals who are overweight and obese. The data shows that 30.8% of overweight and 39.6% of obese individuals do not engage in exercise weekly. Moreover, a considerable portion—43.74% of overweight and 36.7% of obese subjects—exercise only 4 to 5 days per week. In contrast, those in the underweight and normal categories tend to be more active, with the majority engaging in regular exercise each week. Only a small fraction of these groups report not exercising at all. This distinction highlights the significant variance in physical activity levels across different weight categories.

Research from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health suggests that many factors affect daily calorie burn, such as age, body size, and genetics, but physical activity is the most changeable and controllable factor. An active lifestyle is essential for weight management and lowers the risk of heart disease, diabetes, stroke, high blood pressure, and certain cancers, in addition to reducing stress. These insights demonstrate the critical need for regular physical activity for the health and well-being of individuals across the entire weight spectrum. From this visualization, viewers may understand that obese people exercise as well, and many times are not suffering from this illness due to a lack of movement and laziness. It should also be noted that not all individuals are able bodied and able to exercise. This visualization should therefore be analyzed loosely, with that consideration in mind.

Regular physical activities emerges as a key strategy in combating the ‘middle-age spread’—an increase in abdominal weight that tends to occur as people grow older, and which is notoriously more difficult to reverse than in one’s youth. Our study categorized subjects into age brackets of 14 to 30 and 30 to 61, demonstrating a clear shift in weight categories with age. Youth, specifically those between 16 to 26, showed higher instances of normal or underweight statuses. There is a discernible rise in overweight statuses and obesity levels 1 and 2 in the post-30 age group, showcasing the occurrence of weight gain as a natural part of aging. NIH News in Health highlights that losing weight and sustaining physical activity become significantly more challenging during mid-life. This difficulty may be partially attributed to biological shifts, as research by Dr. Jay H. Chung of the NIH has found that an enzyme called DNA-PK can slow metabolism and hinder fat burning. Complementing this, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health stresses the difficulty of weight loss in later years, advocating for proactive weight management. It emphasizes that an active lifestyle is crucial for maintaining a stable weight, whereas a more inactive life can contribute to gradual weight gain over time. These insights collectively reinforce the importance of preventative health measures and regular exercise to counteract age-related metabolic changes and maintain a healthy weight.

Physical exercise is undoubtedly beneficial for weight management, yet its effectiveness is greatly enhanced when paired with a diet lower in calories. Our graphical analysis indicates a significant positive correlation between obesity and the frequency of consuming high-calorie foods, as well as vegetable intake. The data shows that a high intake of calorie-dense foods is prevalent across all weight categories, with 80.9% of underweight, 73.93% of normal weight, 83.64% of overweight, and a striking 97.74% of obese individuals regularly consuming such foods. The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health reinforces this relationship by asserting that when calorie intake exceeds the amount burned by the body, weight gain ensues. Hence, combining regular physical activity with mindful dietary habits that focus on caloric balance is critical for effective weight loss and long-term weight management. This may allow for viewers to understand the importance of healthy choices of consumption, and which food group should be preferred. However, it must be noted unfortunately that not everyone is able to afford healthy foods, and have no choice but to eat fast food that contains ingredients of lesser qualities.

Design Process and Principles

With our cleaned data, one of the first visualizations we experimented with on a worksheet on Tableau was corresponding age and weight. We were able to quickly see that the ages between 18 and 27 had the highest rate of obesity. This was surprising, as they are assumed to be more active compared to people who are further in their adulthood.

An infographic was created on Canva to showcase the findings of our visualizations. We used a template to support the creation of the layout of the infographic, and then tweaked everything else to make it our own. The aim of this article was to transfer our findings onto a more visually engaging format, so that more individuals could learn about the complexities and causes of obesity. A section was dedicated to showcasing how genetics play a significant role in cases of this illness, and it should not be brushed off as a person being lazy or making unhealthy eating habits. Another section is about social stigma, to address the greater issues that lead to shaming of obese people, in real life and in the media, connecting it back to genetics as well. Onwards, our next investigation in visualization is mentioned, about physical exercise and obesity, and then about calories in food and eating habits. At first, we did not contain information about our findings, such as overweight and obese individuals having a higher risk of obesity due to their genetics, and added those later to deliver a more refined graphic. Initially, our infographic also only had graphic drawings. We switched them out with our visualization findings instead, to provide direct results of percentages.

Expressiveness and effectiveness was considered while creating the infographic. For spatial region, negative space was needed to allow the text to be spaced apart, for the readers to read it in a clear manner. A lot of informative text was eliminated, and simple colors were chosen to make it simple and not overwhelming.

Pros and Cons of Designs

A positive aspect of our designs is that our inputs, which create comparisons through visualizations, are very easy to understand for the average viewer, as they relate to the human body. This catches the interest of the audience, as most people already have background information about the causes and effects of obesity due to its presence in popular media. Another aspect that reflects the strong dataset is that it provides extensive dimensions of different variables, from personal background to lifestyles. It covers valuable information that could analyze the cause of obesity and get to know more about obese people’s lifestyle.

However, the dataset itself is also flawed in which the data is not consistent. For example, male participants outnumber female participants, which may lead to biased and inaccurate comparisons regarding gender. Additionally, due to the uneven distribution of data in terms of the categories in BMI, we had to tune our visualization to be related to percentages only. This unfortunately confined our creativity when generating graphs. Lastly, BMI is nowadays considered as not the most accurate way of representing one’s weight in relation to their body. More complex measurements and calculations could be made for future visualizations for a more realistic comparison, which may take more time.

Works Cited

Barquera, S., & Rivera, J. A. (2020, September). Obesity in Mexico: Rapid epidemiological transition and food industry interference in health policies. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7434327/

Jimenez-Mora, M. A., Nieves-Barreto, L. D., Montaño-Rodríguez, A., Betancourt-Villamizar, E. C., & Mendivil, C. O. (2020, June 3). Association of overweight, obesity and abdominal obesity with socioeconomic status and educational level in Colombia. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity : targets and therapy. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7276377/

Obesity: Causes, types, prevention & definition. Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/11209-weight-control-and-obesity

Palechor, F. M., & Manotas, A. D. la H. (2019). Estimation of obesity levels based on eating habits and physical condition. UCI Machine Learning Repository. https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/544/estimation+of+obesity+levels+based+on+eating+habits+and+physical+condition

Summer, E. (2017, June 4). 40% of Peruvians are overweight and obese. PeruTelegraph. https://www.perutelegraph.com/news/peruvian-curiosities/40-of-peruvians-are-overweight-and-obese

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Causes and risk factors. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/overweight-and-obesity/causes

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (n.d.). Health Risks of Obesity: Medlineplus medical encyclopedia. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000348.htm

This project focuses on the multifaceted nature of obesity, including the genetic aspect and social factors, such as not exercising and eating high-calorie food. The use of infographics is particularly commendable because it transforms complex data into an accessible and visually appealing format that can easily communicate the message to a broad audience. By focusing on the different aspects of obesity, the project takes a stance against the oversimplification of obesity’s causes. The inclusion of exercise and diet patterns offers a comprehensive view that is both informative and enlightening.

For improvement within the next few days, attention could be given to ensuring the data represents a balanced cross-section of the population, considering gender and age demographics. For example, maybe, visualize the obesity rates for men and women separately? Additionally, enhancing the infographic’s interactivity could deepen engagement, perhaps by allowing viewers to explore how diet or exercise frequency changes might affect different demographics.

In terms of future development, the project could extend its scope to include longitudinal studies, tracking changes over time to reflect the impact of interventions. It would also be beneficial to investigate the psychological effects of obesity and the social stigma, perhaps through qualitative research, to add depth to the existing quantitative approach.

Lastly, this project serves as a valuable tool for education and advocacy. Its empathetic approach towards the individuals affected by obesity is not only commendable but necessary for driving social change. Overall, your group did a really good job highlighting such an important issue with sensitivity and scientific rigour!

Fangyi, Rachel and Heather