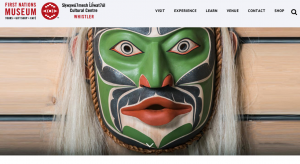

Module 2 examined stereotypes and the commodification of indigenous social reality. My weblog for this module explores some of those issues but it also continues to represent my search for understanding using the two-eyed seeing approach. This entry contains several examples of online resources that support teachers in growing their understanding of the many complicated issues and understandings involved with the integration of traditional Western and Indigenous approaches to learning.

Math Catcher: Mathematics Through Aboriginal Storytelling

Math Catcher is an initiative launched by various educational institutions and the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in the Mathematical and Computational Sciences. It is based on the belief that it is crucial to engage Aboriginal students in mathematics and science at an early age. The program supports various initiatives including a math camp and a series of film resources for classroom teachers. The films feature a small indigenous boy named Small Number and they explore various mathematics and science concepts through First Nations imagery and storytelling. The films are made in a variety of First Nations languages and in English. I have personally seen some of these films used in the classroom to great effect.

FNESC (First Nations Education Steering Committee): Science First Peoples

This is a free downloadable online resource for teachers that introduces teachers to the understandings necessary in order to effectively integrate First Nations ways of knowing into their science teaching. FNESC has previously published similar guides for Mathematics and English. The guide details how teachers can use various place-specific themes to explore issues that are relevant to Western and Indigenous cultures. It also provides suggestions for how teachers can develop local resources to support their practice and it provides information on indigenous ways of knowing and worldviews. This resource focuses on how Western and Indigenous understandings of science are complimentary. It does not value one above the other. This approach is helpful to teachers struggling with concerns that Indigenous and Western ways of knowing may be antithetical.

Integrating Western and Aboriginal Sciences: Cross-Cultural Science Teaching

This paper by Glen Aikenhead was published in 2001. It discusses the integration of Western and Aboriginal Sciences in a fascinating way. It views the process of “coming to knowing” of science as a cultural negotiation in which students must experience learning as a cross-cultural event. “Success at learning the knowledge of nature of another culture depends, in part, on how smoothly one crosses cultural borders. . . In short, a science teacher needs to play the role of tour-guide culture broker”. The educator makes border crossing explicit and is clear about which culture they are talking in at any given moment. The students could be exploring the culture of Western science in the context of Aboriginal knowledge or vice versa. This article has given me a great deal to think about as it introduces the importance of identifying the colonized and the colonizer and teaching the science of each culture. The article seems to focus primarily on teaching Aboriginal students.

This paper by Mary Battiste was first published in 1988 but it has been reprinted many times and can be easily found online. In her paper, Battiste rejects the idea that the “add and stir” model of integrating indigenous knowledge and cosmology holds any promise as a means of reconciliation or Aboriginal student success. She contends that in order for education to be meaningful for Aboriginal students, it must include content in the form of language, epistemology and ontology. She emphasizes that Aboriginal language must be embraced and nurtured in education and that language is not simply a series of sounds but rather the socialization of language and knowledge, ways of knowing, and nonverbal and verbal communication.

Assembly of First Nations: Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge and Intellectual Property Right

This discussion paper was published in It discusses the problems with the concept of Intellectual Property (IP) as it relates to Aboriginal Traditional knowledge. Aboriginal Traditional knowledge (ATK) is explained and discussed, as is the concept of ownership as it exists in the context of ATK. The crux of the argument is that the IP system is not suitable for protecting ATK, because it demands that ATK fully conform to western epistemology and be proven through western empirical methods in order to be considered valid. It claims that using the notion of “academic rigour” to determine validity of ATK is another form of cultural imperialism. Ultimately it urges the reform of IP laws and the creation of a separate legal regime within the IP system in order to provide legal protection to ATK.

Cultural Survival

Cultural Survival