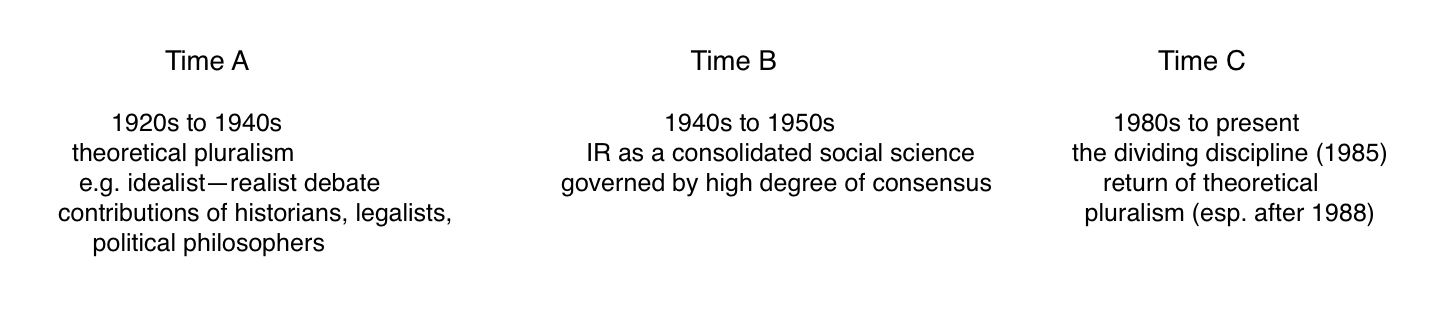

As Milja Kurki and Colin Wight point out, “It is reasonable to assume that a book” (and in our case a course) “dealing with IR theory would provide a clear account of what theory is” (p. 25 of Dunne et. al.). But it is no longer possible to presuppose a shared vocabulary about anything in international relations, and this includes theory, where “direct comparison between theoretical claims” has become exceedingly difficult. These authors go on, rightly, to distinguish different types of theory, something not necessary prior to the 1980s, when just about everybody thought of theorizing, regardless of perspective, as an essentially explanatory activity aimed at establishing patterns, cause and affect relationships, and identifying—even solving—problems. It is no longer possible to pretend that this is the only sort of theory that matters in IR, or that we can ever have a clear, agreed upon definition of what theory is. It is possible, however, to be clear about how we arrived at this point.

The American poet Walt Whitman, noting his own quirks and imperfections, famously wrote: “very well then I contradict myself; I am large, I contain multitudes.” Appearances and caricatures to the contrary, IR never was, and never will be, a unified discipline. It has always contained multitudes, despite a concerted effort by early architects of the field to ignore or suppress contending versions of theory. One of the first casualties of this preoccupation with conformity were political philosophers whose decidedly value-laden, normative, and non-scientific (i.e. non-falsifiable) musing about “the good life” were under attack in the 1950s by political scientists bent of making a sharp distinction between mere political philosophy, and the superior activity of political theory. This agenda spilled over into the subfields as well, and only recently have political philosophers regained entry into IR discourse under the general label of normative IR, though Steve Smith (rather strangely) does not include this as a distinct IR theory so much as set of reflections on the field’s disciplinary identity. Even more strangely, Smith says there are 8 distinct theories of IR, despite the reality that he goes on to list 10 theories! If you are confused, you are not alone.

One way to cut through the confusion is to accept Chris Brown’s characterization of the discipline as a “bizarre forty year’s detour from normative theorizing.” On this view, it is not theoretical pluralism that is aberrant but the preoccupation with conformity that for nearly half a century students of IR were taught to regard as the only viable path to theoretical progress. There was division all along, in other words, despite strong efforts to create a realist monopoly on thinking politics, and a positivist monopoly on theory. Even realist felt this pressure, and were taken to task by their “neo” or scientific counterparts for lacking methodological rigour.

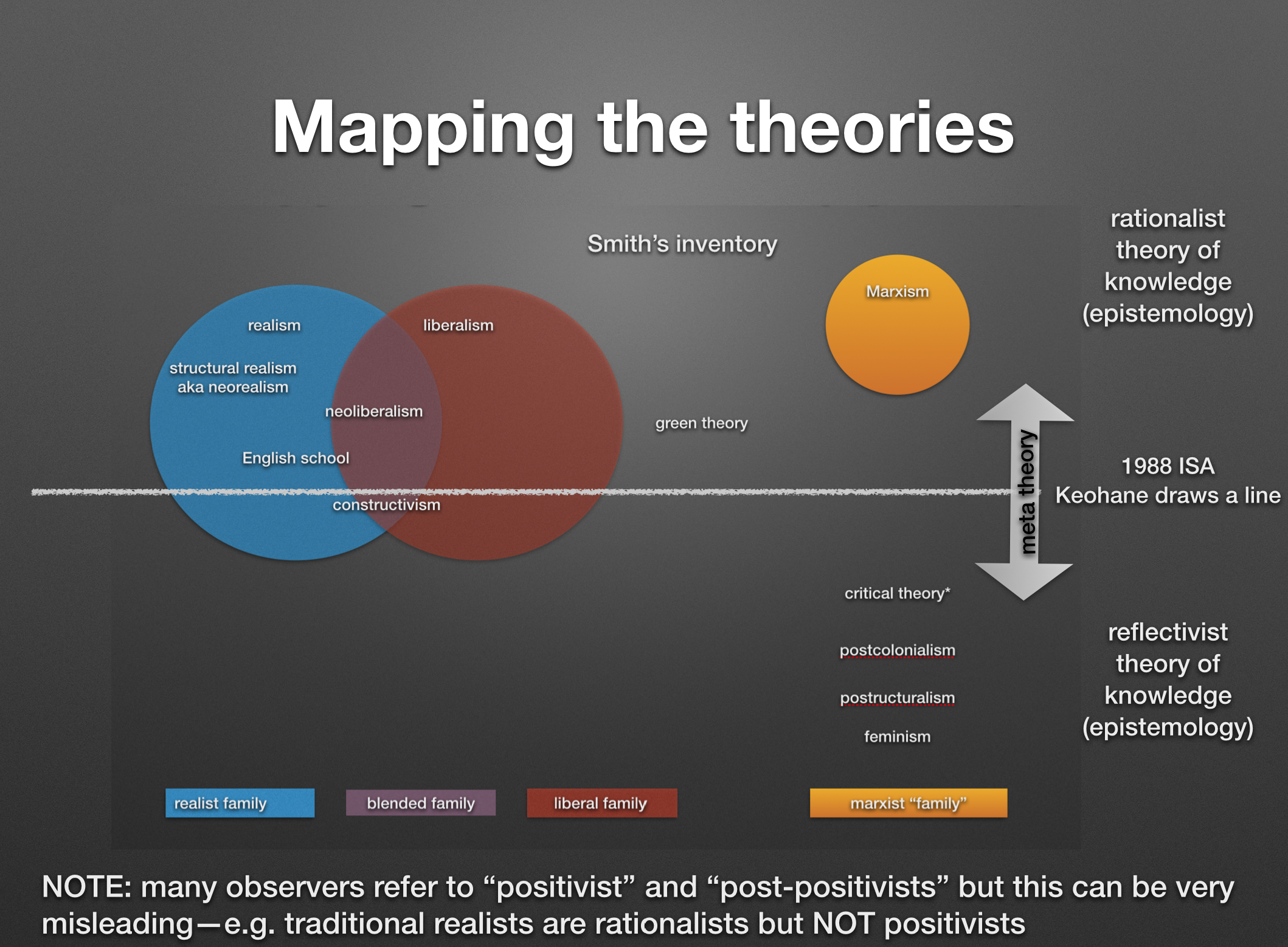

To sum up, IR has always been home to more than one perspective (realism vs. idealism for example) and more than one sort of theory (rationalist/explanatory vs. reflectivist/understanding). Robert Keohane’s claim that reflectivist account did not arise until the end of the 1980s is thus misleading, but such approaches were certainly treated with hostility in the past. Because many of these approaches are “meta” in nature (theories about theory) IR has never been more diverse, but it has also never been more complicated. The following map, hopefully, schematizes major divisions and positions.