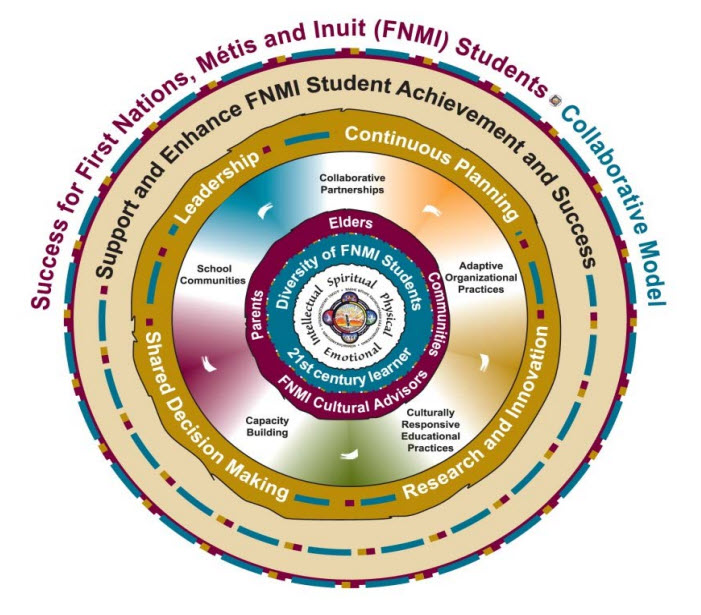

Though my research question focuses on instructional design processes, I find that as an Indigenous instructional designer I am curious about the instructional designers themselves who must choose to use those processes, and are entrenched and trained in a non-Indigenous system.

The article, “Agency of the instructional designer: Moral coherence and transformative social practice,” by Katy Campbell, Richard A. Schwier, and Richard F. Kenny, looks at instructional designers as more than purveyors of education and instructional frameworks. Instead, they view them as purposeful educators who have ethical, social, and political views and have moral obligations.

“We maintain that instructional design is a moral practice that embodies the “relationship between self concept and cultural norms, between what we value and what others value, between how we are told to act and how we feel about ourselves when we do or do not do act that way” (Anderson & Jack, 1991,p. 18). Instructional design involves the ethical knowledge of the designer acting in moral relationship with others in a dialogue among curriculum, the sources and forms of knowledge and power, and the social world. As ethical actors in that world we use the language of design in collaborative conversation with our colleagues, our clients, and our institutions to create an alternate social world of access, equity, inclusion, personal agency and critical action.”

The references reveal the influence of feminist theory which serves as a critical lens on this research. Though only one of the instructional design examples notes a designer working with first nations, the authors in both examples challenge the expertise an instructional designer brings to their work as it is entrenched in just one knowledge system. They call for instructional designers to be aware of their cultural biases, values, sense of morality, and the political implications of their choices.

They quote an excellent line from Kugelmass (2000, p. 179) – “Who am I, why am I practising this way, and what effect does this have on others?”

Campbell, K., Schwier, R. A., & Kenny, R. F. (2005). Agency of the instructional designer: Moral coherence and transformative social practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 21(2). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.1337