Module 4 Blog Post: Dumb Ways to Die

Julie Zhang

After reading this week’ chapters about narratives and imbuing style into the message, I felt a highly relevant but neglected concept was that of (internet) virality. To satisfy my curiosity, I delved into some literature on what makes certain online content go viral and found a great study addressing this query by Berger and Milkman. The two researchers analyzed several thousand New York Times articles according to three dimensions—valence (positive versus negative information), emotionality and likelihood of producing specific emotions—to understand what makes certain pieces more widely shared than others. Similar to what was discussed in the textbook, Berger and Milkman concluded that to produce viral content, one should:

- Have a positive message; and

- Produce emotional arousal/activation.

Additionally, the researchers found virality is elevated when the information is interesting, surprising and useful. A final key insight is that not all emotions are equal – while sadness is considered low-arousal and therefore does not make for as contagious a message, high-arousal emotions like anger, amusement and awe increase the likelihood a message will be attention-grabbing and shared via social networks. However, as the authors stated in their lay article in the Scientific American, “causing some emotion is far better than inspiring none at all” with respect to increasing social transmission of information.

In exploring the idea of internet virality, I was reminded of one of the most compelling online communication products I have ever witnessed: Metro Trains Melbourne’s 2012 “Dumb Ways to Die” campaign.

This admittedly strange but thoroughly entertaining video was made by the Australian rail network to discourage people from unsafe behaviour around train tracks. The “Dumb Ways to Die” campaign taps into many of the strategies proposed in our readings and in Berger and Milkman’s study for crafting an effective message. The video uses brief stories to paint the meaningful overarching moral of exercising prudence in everyday life, especially around trains. It also draws attention though the catchy music and cute characters. Most importantly, the campaign leverages a positive emotion, humour, and pairs it with a healthy dose of shock, another activating emotion, to create an unforgettable message. Unsurprisingly, this music video absolutely exploded, with over 185 million views on YouTube to date, inspiring spin-off videos and games, and winning multiple digital content awards. As proof of its lasting impact, I am still able to sing the chorus and remember the key lesson eight years after first seeing the video.

In sum, if online communicators appropriately wield the psychological and emotional tools for developing viral content, they can spread their message easily and rapidly across the globe and produce a lasting impression on all who sing their tune.

(Word Count: 446)

References

Module 4 Blog Post: Making Food Safety Personal

Laura Chow

The concentration on narratives this week has left me reflecting on the use of shock narratives to present the concept of foodborne illnesses or food safety to food handlers. Food handlers (i.e. people who prepare or serve food to the public) are required to have some level of food safety training. This is often done through a FoodSAFE certification, comprised of an eight-hour course usually taught by Environmental Health Officers. While a major generalization, it is not uncommon for food handlers to have limited English skills or not much more than high school education.

In 2016, the FoodSAFE course was revised to provide more images and stories to help students relate more to the material. This included a number of descriptions of peoples’ experience with food safety as consumers:

While we read this week that narratives can help communicate a point, these stories come across as a little disingenuous, appearing largely for their shock factor and almost too high level to play on individuals’ emotions. While all reflecting a negative health outcome if food safety is not made a priority in the kitchen, they are presented as news stories that don’t fully reflect the negative experience of someone who has experienced the injury.

For example I found a blog entry where the author detailed her first-hand experience with food poisoning. The detail she expresses comes across as a true reflection of her experience that may be shared with others and provides a first-hand account of the experience. Her story is personal and reads less like a news headline and more like a personal diary. Even to me, this resonated more with me than the examples provided above, leaving me to wonder if FoodSAFE presented their narratives more as personal stories, if they would stick with participants more.

This week’s module highlighted that simply providing a story is not sufficient in making materials easier to digest. Perhaps if the materials in the FoodSAFE materials were presented in more of a true narrative style presented more of a first-hand account and reflected how the food handler could have prevented the incident (i.e. providing clear plot points and providing repetition to the main message) it would resonate more with the students taking the course, enabling them to put it more into practice.

References:

Burton, T. (2016). Foodsafe level 1: participant workbook. Victoria, B.C.: Crown Publications, Queens Printer.

Module 4 Blog Post: Morality, Intuitions, and Values

By Sean Sinden

Our readings have mentioned the importance of acknowledging, understanding, and leveraging the values that people may hold. These values may affect what they perceive as fast, how serious they consider a hazard to be, or how they are swayed by narratives, among many other things. This reminded me of a book that we used in Dr. Kershaw’s Knowledge Translation class last term. The book is called The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt, who studies the psychology of morality.

Haidt describes a theory of moral thinking where people react to stimuli (a fact, a speech, a TV show) in two distinct parts. First, we have an unconscious, intuitive response. Intuition is then followed by reasoning, which acts to justify the unconscious reaction that preceded it. In this way, focusing specifically on getting people to change the way they reason about something is a dead end. He describes our worship of reason as “rationalist delusion”. In short, there is more to a message than just the facts.

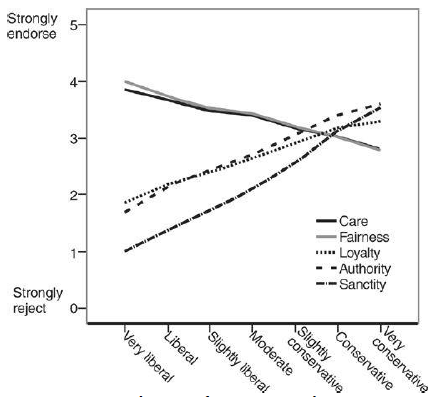

He goes on to describe, backed up by sociological and psychological research, six moral foundations that combine to affect our intuitive responses (and reasoning) about particular scenarios.

- Care/Harm: makes people sensitive to suffering and need, dislike cruelty, and want to care for others

- Fairness/Cheating: makes people like those who they can collaborate with and want to shun or punish cheaters. It can also make people care about the idea of proportionality — “you get out what you put in”.

- Loyalty/Betrayal: makes people like team players, and reward them, but dislike and ostracize people who betray us

- Authority/Subversion: makes us want to “respect our elders” and dislike people who subvert hierarchies

- Sanctity/Degradation: *this one is a little tricky to describe quickly… it’s about symbolic objects and threats…*

- Liberty/Oppression: makes us sensitive to people who try to take control and to band together to overthrow tyrants

Haidt then takes the structure of these foundations to describe how they can explain how people can so adamantly disagree on a topic. One of the most relevant examples he describes is the difference between the political left and right in the US. People on the extreme left care more about Care, which declines as you move right on the political spectrum. Right-wing people care more about Loyalty and Authority. They also feel more strongly about fairness as proportionality while liberals care more about fairness as equality.

Take the example of communicating about the social determinants of health. The idea that a person in poverty deserves society’s help and caring resonates and makes sense to a liberal person. A right-wing person on the other hand will reject the idea that anyone deserves a handout before you can even get the rest of your message across.

A person’s mix of moral foundations is set by culture, upbringing, and a wide range of other factors.

The point is that we need to think very carefully about what moral foundations our messages may trigger and the values of the people to whom we are communicating.

//

Word count: 500

Module 4: Tainted Water through a Style vs. Substance lens

Brandon Wei

Although I used the investigative series Tainted Water in my last blog post, I think our face-to-face class sparked a really interesting discussion about one of the articles that I’d like to further address here through a style vs. substance lens.

Both my colleagues’ article on lead-tainted water in Prince Rupert and my own team’s piece on corrosive water in Whistler had a very intentional narrative style with specific story elements: we wanted to amplify voices of those worst affected and those least able to do something about it — groups that, when it comes to public health issues, I find are often one and the same.

In the Prince Rupert article, it was Leona Peterson: a single mother living in a subsidized Indigenous housing complex with her young son. Marginalized communities so often face the brunt of environmental racism and First Nations in Canada face arguably the toughest challenges with drinking water. If I had to define a “goal” of that story, I would say it would be to raise awareness of the issue and make government — who knew about the problem for some time — answer why it still wasn’t fixed. I also think that hazard for residents like Peterson’s son > outrage amongst the general public, so if the story did ramp up outrage on his behalf, perhaps it’s more representative of the hazard.

As for our Whistler story, our main character was also a parent: father John Wallace whose house’s tap water tested 12 times the federal guideline for lead. We highlighted his concern for his two-year-old son, because young children are among the most susceptible to adverse health effects of lead — and they’re not able to do much about it. Our story definitely sparked outrage given Whistler’s water reputation.

And while I don’t know if I can say we had a central message, I do know that, like in every news story, we had to try to balance style and substance to tell a sound and striking story. Comparisons were used in both stories when the concentration of lead tested at the tap was compared to the federal government’s guideline for the maximum acceptable concentration of the metal. We felt this was important to show what the situation is versus what the situation should be, according to Health Canada. We focused on very specific characters, wanting to harness the power of emotion and strike at the hearts of readers, as Olson would say. And, maybe most relevant of all this course, we had to work with lead experts to interpret the results and describe them and their implications accurately.

And after the investigation launch, funnily enough, the experts published their own article on The Conversation on how to how to keep homes, schools, daycares and workplaces safe.

____________________________________________________________________

Module 4 Blog Post: Hurricane Katrina & Crisis Communication

Gabby Hadly

After finishing this modules readings I had a bit of a crisis communication ‘fever’. As someone that lived in Texas during Hurricane Katrina I couldn’t help but notice that most of the components of ‘crisis and emergency risk/response communication’ from this modules readings were not utilized during / after Katrina. To see if my memory was serving me properly, I did a bit of a dive into the preparation, response and aftermath of the hurricane. Many researchers have studied for years now what led to Katrina being so deadly and destructive (besides the magnitude of the storm). They also examined what the US could have done better before, during, and after the storm- and looked to see the improvements that have been made since then in the realm of risk/crisis preparedness and communication around natural disasters.

The main things they found were that during Katrina:

- Precise and clear messages coming from trusted sources did not happen

- Volunteers were not welcomed to help with rescues

- Evacuating animals was not a priority or even allowed

An additional finding from these studies was that coastlines are left incredibly vulnerable to natural disasters (especially in the face of climate crisis) , and the US has done little to nothing to prepare or mitigate the potential devastation these communities will inevitably experience when the next storm strikes. This made me think that we must also consider prevention and awareness of potential crisis in good risk/crisis communication messages.

This research led me to realize that while the the six principles of crisis and risk communication laid out by the CDC are essential– they fail to incorporate some practical aspects of emergency response in the real world. For example, one of the reasons many New Orleans residents did not evacuate was because evacuation messages told them to leave their pets behind. This is something that the US made certain to not do when calling for evacuations during Hurricane Harvey. Therefor, effective crisis communication must also consider if citizens will and can do the orders being asked of them. To that end, many of the most vulnerable individuals in New Orleans didn’t have cars or a means of evacuating, resulting in many of these people ignoring repeated evacuation messages. Therefore effective communication messages must also consider the means of their target audience.

I also did some research into why some people ignore evacuation orders. While a major reason is internal bias (or people not thinking the disaster will effect them), another is who the message comes from; if it comes from someone of an authoritative position, people are more likely to comply with the message. For example, in this famous video the Governor of New Jerseys delivers a clear and bold message of ‘Get the hell off the beach’ which coupled with his authoritative government position resulted in an effective crisis communication message.

I think the take home message is that you need to go beyond the six principles of effective crisis communication when developing good crisis messaging. For example, effective crisis communication needs to also address factors that affect response (such as individual characteristics and values, the message itself, perceptions, and message source).

References / additional readings:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10417940802219702

https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1463674830481-16ed0020684ba8cd263ba88f54a48c95/TemplateEmergencyCommPlans_IPAWS-508_05192016.pdf

https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/is/is242b/student%20manual/sm_03.pdf

Module 4 Blog Post: Griot in Mali

Nilou Tafreshi

Storytelling has played an important role in cultures all around the world. I saw this first-hand when I was living in West Africa.

In Mali, a storyteller is known as a ‘Griot’ and they are not just any storytellers; being a Griot is a privilege, an honour, and it often runs in families. Griots date all the way back to thirteenth century Malian Empire (1).

Since many people could not read or write, Griots used oral storytelling which continues to this day. Griots are respected members of society who play an important role in preserving Mali’s history, culture, and heritage.

The Griots’ “performance” can be in the form of an entertaining story, song, dance, or speech. I was lucky enough to witness a Griot who visited my host family when I was living in a small village in Mali. He told a story that was in the shape of a poem that turned into song; he used humour and facial expressions to get his points across. Even though I only understood the French portions of the story, I was engaged the entire time!

Here are a few examples of Griots:

Interestingly, Griots also use the storytelling essentials discussed in the module and do a fabulous job of building a narrative. The creative and diverse way in which they tell stories also allows them to use many of the storytelling frameworks we have discussed. I will outline some stories I heard from Griots below as an example and discuss how they could be related to content in this module:

- The Griot will identify his audience often by finding out the family’s last name as in Mali the last name of an individual tells you a lot about their background, religion, and language. This then allows the Griot to choose characters that would be appropriate to the family. For example, people with the last name “Coulibaly” are famous and numerous in Mali and are often made fun of (usually affectionately) when in reality they have made many positive contributions to society. A Griot might choose a classic underdogs-coming-out-on-top story when performing for a Coulibaly family.

- A Griot might tell a story about the risks of not listening to your family when speaking to young people. This could be a story about a young man who decides to disobey his parents, not help his brothers and sisters on the family farm, and end up in a dire situation in the end.

- A Griot may also tackle more controversial topics; like having up to four wives, which is very acceptable in Malian culture especially among Muslim people ( for example my host father had two wives who got along great to my utter shock).

Can you think of a modern-day western example of a Griot?

Reference: Marchand, Trevor H. J. “‘It’s in our blood’: Mali’s griots and musical enskilment.” Africa: The Journal of the International African Institute, vol. 85 no. 2, 2015, p. 356-364. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/581094.

Blog Week 4: Keeping up with Expectations

Alison Knill

The concept of style versus substance this week in communicating had me thinking about a topic that always gains a lot of attention at the start of the year: New Year’s Resolutions (or lack thereof). Every year there’s news articles and blog posts describing how to keep your resolutions this year, or personal experiences explaining why the goal was unachievable.

The type of information generally seems to split into either the very style focused category (blogs), or the more substance focused category (science news). Behavioral Scientist very much takes the substance route as the article goes into detail about research from MIT explaining why long-term goals are so difficult. It uses a bit of personable style by relating to the common trouble of achieving resolutions, but for the most part, the article is a culmination of hard-hitting facts and research.

In contrast, more blog-style articles, such as the one seen on Woman’s Day, cater to using style in order to establish a personal connection with the reader. You feel like you can relate to how the writer is feeling about her own goals as you read through the article, making their advice on how they kept their goals seem like something you can trust. That’s not to say there’s no objective, fact-driven substance. The writer includes statistics about how many people will abandon their goals by February (80 per cent!) and quotes from a professor psychologist, but the main takeaway I get from the post is the style: relatable and forgiving.

Similarly, Forbes wrote an article that had a distinct outline for their style, breaking down how their resolution tips into five easy sections. Reading through it, I didn’t see anything concrete about what they were basing their tips off of, but it sure felt like they were personally offering me advice.

For those wanting an even more stylish touch, NPR outdid everyone by a resolutions poem titled “Ode to the things I’ll get to tomorrow” (that sounds an awful like my usual procrastinating self, not just New Year’s resolutions).

Failing a New Year’s resolution isn’t necessarily a crisis situation, but it is something that can have a psychological impact on a lot of people. No one likes to fail, so communicating ways to help people achieve their goals is important. Looking at what’s available to read, though, it seems like there’s a gap in articles that balance both style and substance to make the advice both relatable and trustworthy.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/investigations/2019/11/04/there-is-lead-in-our-water-dont-doubt-it-just-start-flushing-says-prince-rupert-resident-whose-water-tested-three-times-the-national-guideline/leona_peterson_carrying_water_cooler_bottle.jpg)