Category: Inquiry

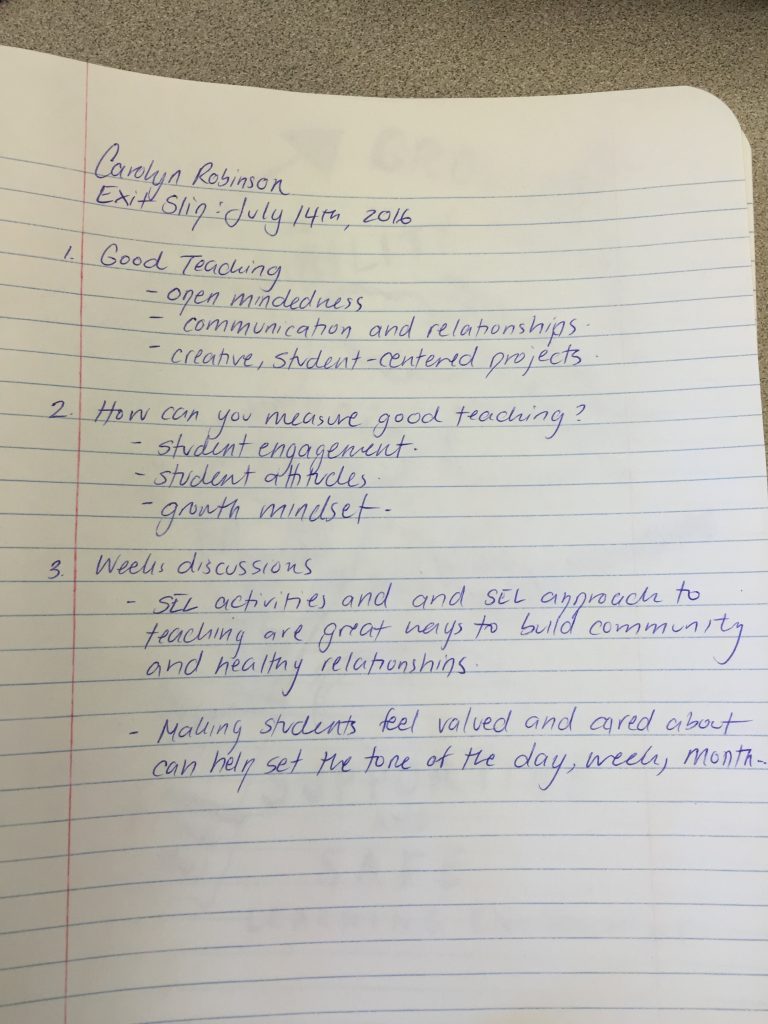

Inquiry Class Exit Slip: July 14th, 2016

Improving Behaviour: To Act Without Prompting

Over the past several weeks the majority of my research has focussed on how good teaching practices can help minimize instances of disruptive behaviour within the classroom. Although I feel as if my inquiry has opened my eyes to so many ways that I can be a better teacher for all of my students, I still found myself being curious about one thing — student internal motivation. How can I get my students to want to choose to behave appropriately in the classroom and in social situations without teacher encouragement, reminders, and presence? In other words, how can I get my students to act without prompting?

Upon reading through a variety of articles on internal motivation I stumbled across one article that I found to be particularity enlightening. In the article “How To Build Classroom Community: It’s Not What You Think” author Michael Linsin discusses how the process of building a strong classroom community can help improve both student motivation and student behaviour. Within the article former fourth-grade teacher Michael Linsin notes that, “…the whole idea of having a strong [classroom] community is that we want our students to act without prompting. We want teamwork and camaraderie to be who they are and how they choose behave, not something foisted upon them by the teacher” (2009, p.1). Linsin asserts that when students act in a kind and appropriate way it is not because there is a strong classroom community, but rather, it is the result of a strong classroom community (2009). Specifically, it is stated that in order for students to properly build a strong classroom community their teacher must first create an enticing goal, then make sure that every class member is needed to achieve the goal, and finally, make sure that there is a chance of failure (Linsin, 2009). Overall, the article outlines that if the above three conditions are implemented correctly by the teacher, the close bonds that students will develop through these repeated experiences will carry over to everything they do in the classroom, including how they choose to behave (Linsin, 2009).

At this point in my inquiry research, this idea speaks volumes to me. Personally I love how this article approaches the topic of disruptive behaviour from a slightly different perspective, a perspective in which the teacher provides the right conditions for building a strong classroom community, but where the students are responsible for building the camaraderie, teamwork, and togetherness that is necessary for success. Furthermore, I find this perspective to be refreshing but also promising.

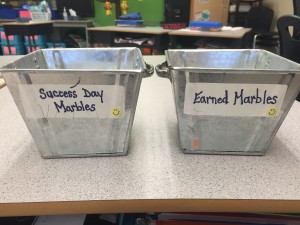

This idea of building community through a collective goal to improve student behaviour is something that I have been lucky enough to experience first-hand this past year. In my practicum class there are 2 buckets of marbles known as the ‘success day marbles’. In one bucket there are 100 marbles, each one with the potential to be earned by the class when they demonstrate collective teamwork. The second bucket is where each earned marble is placed when they entire class successfully accomplishes a goal together. Once all 100 marbles have transferred from the first bucket to the second it signifies that students within the class have successfully worked together to earn an entire day celebrating their teamwork. On this day of celebration, the classroom will be transformed into a giant blanket-fort and there will be freshly popped popcorn, hot chocolate, candy, and projected movies within the classroom-made fort. This day will be a time for the class to celebrate their collective achievements, celebrate camaraderie, and develop relationships.

As an observer in my practicum class I always thought that the ‘success day marble buckets’ were a great idea to help motivate students, but now I understand that they are so much more then that. In only a few short weeks I will begin my extended practicum, and in a sense, I will be put to the test. Although I am unable to say what challenges and successes I will encounter over these next several months, I can confidently say that I am so thankful for the tools and ideas I have acquired though researching my inquiry topic of disruptive behaviour.

Linsin, M. (2009). How to build classroom community: It’s not what you think. SCM, Online.

Student-Teacher Relationships and Living Inquiry

Student-Teacher Relationships

Over the past several weeks a lot of my research on the topic of disruptive behaviour has been centred around the idea of good teaching practices. In staying with this idea, this week I became curious about whether or not classroom management could be implemented in such a way that it could help minimize disruptive behaviour within the classroom without becoming the focal point of the lesson. Moreover, I found myself wondering if there are any alternative approaches to classroom management that have been proven to be more effective in helping to minimize disruptive behaviour.

Personally I believe that classroom management is an extremely important component of any successful classroom; however, I think it’s only one small part of a much bigger puzzle when it comes to creating a classroom environment that promotes learning, academic achievement, positive relationships, and pro-social behaviour. Although I think that at least some amount of classroom management is necessary within a classroom, there are many reasons why I would want to create a classroom environment that focuses on more then just classroom management. One reason why I feel it is important to move beyond more traditional methods classroom management is because I believe that student academic development, behavioural development, and social-emotional development improve far more in a classroom where the teacher’s focus is on building positive relationships with the students rather than micro-managing activities, behaviours, and noise. In addition to this point I also feel as if it is important to move beyond classroom management because it is both arbitrary and subjective in the sense that what may be seen as disruptive by one teacher may be seen as productive and beneficial by another teacher. For example, during a group activity what some teachers may interpret as noise and disruption I may interpret as learning, communicating, and building social skills. Accordingly, I think it extremely important that we as future educators move beyond the traditional focus of classroom management and concentrate more on creating a safe and supportive environment that encourages meaningful learning, positive relationships, and pro-soecial behaviour.

On a personal level I believe that traditional classroom management is lacking because it often does not take the behavioural or cognitive differences of students into consideration, nor does it take the personal relationships between the students and the teachers into consideration. One article which discusses the importance of student-teacher relationships as an indicator for student success and behaviour is entitled, ‘Student-Teacher Relationships’ and is written by Bridget Hamre and Robert Pianta (2006). Within the article it is noted that positive student-teacher relationships are extremely important to establish within the classroom as they are often huge predictors of student social emotional development and student academic success (Hamre & Pianta 2006). In building upon this idea, the article also discusses recent research which shows that positive student-teacher relationships can also help minimize disruptive behaviour within the classroom, help reduce the amount of time spent on behaviour management, and make learning more meaningful (Hamre & Pianta 2006). These findings within the article are exactly why I feel as if more traditional forms of classroom management are lacking. I feel that with a stronger emphasis on building and maintaining supportive relationships within the classroom, less time would be needed for classroom management and more time could be spent supporting, engaging, and encouraging our students. Furthermore, I strongly believe that with a stronger emphasis on building and maintaining supportive relationships within the classroom that instances of disruptive behaviour would begin to naturally decrease without the need for constant classroom management.

Living Inquiry Take Away

This week our cohort had the opportunity to participate in a ‘living inquiry’ activity in which we got to speak with members from the PL Tech cohort and learn about some of the inquiry topics they are pursuing. Although I had many fantastic conversations with many new people during this time, there was one conversation in particular that provided me with a lot more insight into my own inquiry topic. Jon Green, a member of the PL Tech Cohort has spent the past several months researching his topic of ‘assigning homework’ and whether or not it is valuable teaching tool or a waste of time. Within his research so far Jon has come across many alternative and/or more valuable ways to assign homework to students to make learning more meaningful. One specific example that he gave me from his research is as follows: Instead of assigning endless amounts of homework to your students ask a few of them each day to create their own question on the topic and then get them to teach it to the class. For example, at the end of a math lesson ask 5 students to create their own math question on the topic being taught and then get the students to teach it to the rest of the class on the following day. I think this idea is absolutely fantastic. Not only would assigning homework in this way help students be academically successful in their studies, but it would also help keep the rest of the class engaged during the lesson, which in turn would help to minimize disruptive behaviour.

This new perspective that I was able to gain during the living inquiry activity has really helped me to change the way that I think about minimizing disruptive behaviour within the classroom. Over the past fews weeks I have gained the understanding that good teaching practices and good student-teacher relationships are key in helping to minimize disruptive behaviours, and now I am beginning to understand that there are so many techniques and activities that I can use within my own classroom to help me achieve this goal.

Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2006). Student-teacher relationships. In G.G. Bear & K. Minke (Eds.), Children’s Needs III: Development, prevention, and intervention (pp. 59-71). Bethesda, MD: NASP.

Music and Behaviour Modification

Over the past several weeks my research on the topic of disruptive behaviour has focused on heavily on good teaching practices. Although I am beginning to understand that good teaching practices appear to be the foundation for minimizing disruptive behaviours in the classroom, I found myself wondering if there were any proven methods to teaching that could assist good teaching practices. Once I began examining some of the different literature on this topic, I was pleasantly surprised with some of the research I came across. In particular I was amazed to learn that a lot of research consistently shows that music, and a students involvement in music, is strongly correlated to reduced rates of disruptive behaviour and increased rates of pro-social behaviour.

One research article which notes the connection between music and disruptive behaviour is entitled, ‘The predictive relationship between achievement and participation in music and achievement in core Grade 12 academic subjects’ written by Peter Gouzouasis, Martin Guhn, and Nand Kishor. Within the article, authors explain the results of a longitudinal study in which they conducted a large-scale analysis to see if there was a relationship between student involvement in music and academic success (Gouzuasis et al., 2007). After the thorough examination of three different groups of students, all of the collected results reveal that yes, there is a positive correlation between involvement in music and achievement in achievement in core academic subjects (Gouzuasis et al., 2007). Specifically it was found that students who had participated in band, choir, or music composition, on average, had higher achievement in mathematics, biology, and English (Gouzuasis et al., 2007).

Although the above research findings are impressive within themselves, the authors of this study also found that incorporating music into the classroom not only appeared to improve academic success, but it also appeared to improve disruptive behaviour (2007). More specifically the authors note that, “With regard to social skills and personality traits, [these] longitudinal studies have found that there are personal, social, and motivational effects of involvement in music specifically, and in the fine arts in general. In particular, there is now experimental evidence that involvement in musical activities increases students’ self-esteem and social competences, including the reduction in aggressive and anti-social behavior as well as the increase in pro-social behavior” (Gouzuasis et al., 2007, p.89).

In addition to the above research, music and arts researcher Larry Scripp also argues the exact same point. In the article ‘An overview of research on music and learning’ Scripp argues that music should be incorporated in education for many reasons, with one of the most important being the effect it has on child’s social-emotional development, behavioural modifications, and ability to learn (Scripp, 2004).

As a future educator it is so exciting to learn about the many positive impacts that music can have in the classroom, both academically and behaviourally. Personally I have always found that creating music, playing music, and listening to music have helped me de-stress and re-focus myself in certain situations, and after reading some research on this topic, I am beginning to understand why. Furthermore, as I reflect on my experiences teaching in the classroom so far, I can so easily see how music positively impacts student behaviour. During one lesson a few weeks back, I played traditional Chinese music in the background as the students worked – the students were all so relaxed and clam. Multiple students even commented on how they loved working with the music. Additionally, there are several students in my class that play in the school band, and now that I think about it, every time they return to class after band, they are well-behaved, calm, and happy.

Upon reflecting on my own experiences and discovering a wide variety of literature that links music to minimizing disruptive behaviour, I think it is safe to say that music could be an important part of the puzzle.

References

Scripp, L. (2002). An overview of research on music and learning. Critical links: Learning in the arts and student academic and social development. (Ed. R.J. Deasy), 132-136. Washington, DC. Arts Education Partnership.

Gouzouasis, P., Guhn, M., & Kishor, N. (2007). The predictive relationship between achievement in music and achievement in core grade twelve academic subjects. Music Education Research, 9(1), 81-92.

Can A Teacher’s Verbal Praise Help Decrease Disruptive Behaviour Within the Classroom?

Is there a connection between disruptive behaviour and the amount of praise students receive from their teachers? A lot of current research on this topic reveals that yes there is. In fact, a lot of research emphasizes that there is a very strong correlation between disruptive behaviour and teacher-ceneterd strategies, such as teachers’ verbal praise.

One research article which shows this strong connection between disruptive behaviour and the amount of praise that students receive from their teachers is entitled, ‘Using Teacher Praise and Opportunities to Respond to Promote Appropriate Student Behaviour’ written by Tara Moore-Partin, Rachel Robertson, Daniel Maggin, Regina Oliver, and Joseph Wehby. Within the article the authors evaluate and explain how a lot of recent research shows that teacher-ceneterd stragegies are extremely important in increasing appropriate student behaviours and decreasing inappropriate or disruptive student behaviours (Moore-Partin et al., 2010). Results from a variety of research reveal that students who exhibit problem behaviour within the classroom often have high levels of negative interactions with their teacher (Moore-Partin et al., 2010). Additionally, it is noted that “many of the students identified for having or being at risk for emotional or behavioural disorders [often have a long history] of negative or neutral interactions with their teachers and receive high rates of teacher commands” (Moore-Partin et al., 2010, p. 172). Thus, the importance of using teacher-centred strategies to improve student behaviour within the classroom is undeniable.

In the article, one of the most important teacher-cenetered strategies that is discussed is, “the skillful and consistent use of teachers’ verbal praise provided contingently for appropriate behaviour” (Moore-Partin et al., 2010, p. 173). Research has shown that this teacher-ceneterd approach is an extremely successful prevention strategy as it establishes a positive classroom environment and helps to support students’ behaviour and academic needs. In addition to the use of teachers’ verbal praise, another teacher-centred strategy that has proven to be successful in decreasing disruptive behaviour within the classroom is “the provision of increased opportunities for students to respond correctly to instructional questions, tasks, and commands” (Moore-Partin et al., 2010, p. 173).

As I continue to research disruptive behaviour, I am beginning to understand the significance of good teaching practices when it comes to minimizing disruptive behaviour within the classroom. In many of my experiences in elementary classrooms so far I have witnessed how praise from a teacher has been a positive reinforcer for appropriate student behaviour; however, I never thought to observe if providing students with more opportunities to respond in class had a similar impact.

As I move forward in both my practicum and my inquiry research over the next few weeks, I will definitely start to pay closer attention to how this particular approach impacts behaviour within the classroom. Based on the ample amount of research that has been conducted in this area thus far, I assume that if I were to provide my students with more opportunities to be successful in class, I would most likely notice a decrease in disruptive behaviour. I am excited to experiment with this particular approach in my own classroom in the upcoming weeks, and hopefully, this strategy will help to improve and further develop my current teaching practices.

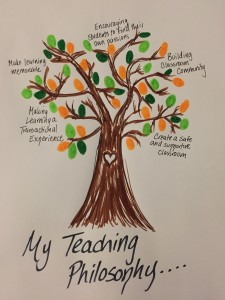

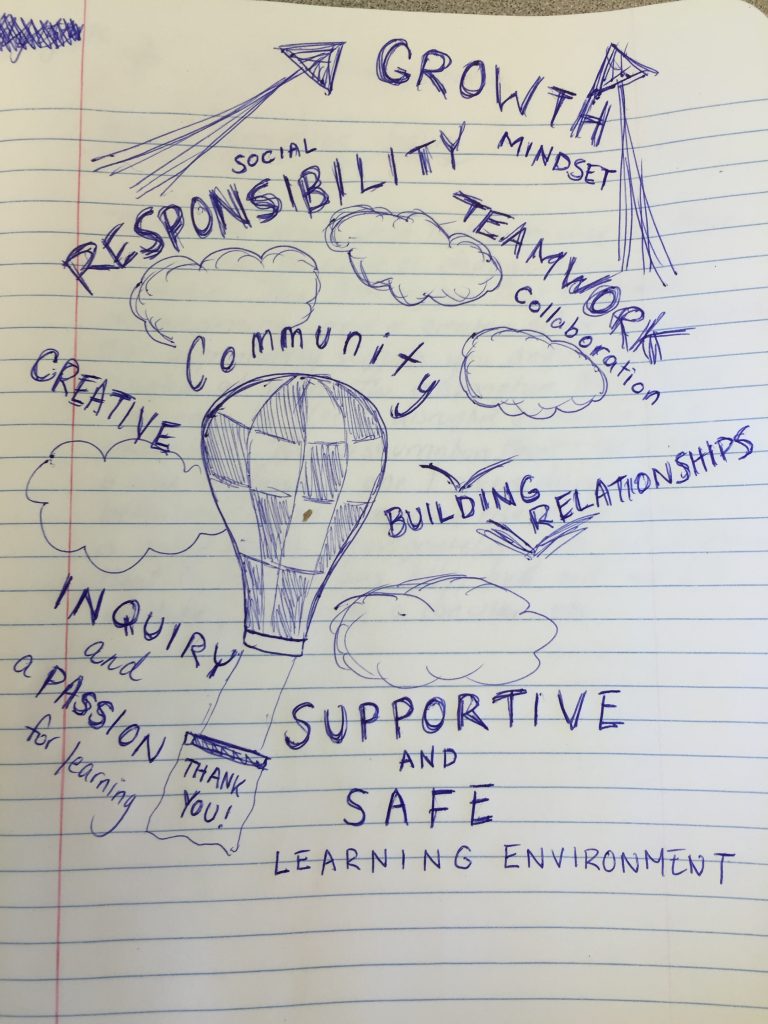

Developing a Philosophy of Teaching Through Inquiry

Since beginning the Teacher Education Program at UBC and completing my first practicum I have become very passionate in my commitment to several teaching philosophies. I am committed to building a strong classroom community, to making learning a transactional experience, and to encouraging students to discover and explore their own passions. Additionally I am committed to creating a safe and supportive classroom environment in which students can work together to build relationships, make connections, and foster a love of learning. Below is a visual representation of who I aspire to be as a teacher:

Although my experiences at UBC and in my practicum class have both significantly inspired my developing teaching philosophy, the personal journey that my inquiry topic has taken me on thus far has also largely influenced my developing teaching philosophy. Researching and learning about disruptive behaviour in the classroom has opened my eyes to an extremely important and relevant topic in education today. More importantly, learning about disruptive behaviour in the classroom has inspired me to be a better teacher. Thanks to the direction that this inquiry project has taken me, I am beginning to understand that all teachers have the power to positively impact every child, even the seemingly ‘difficult’ ones. Based on the research I have explored so far I believe that by creating a safe, supportive, engaging, and motivating classroom environment not only can I minimize disruptive behaviour, but I can also inspire children to pursue their passions and foster a love of learning.

I am excited to continue my research on disruptive behaviour in the classroom over the next few months, and to further develop the teaching philosophies that will one day define who I am as an educator.

Disruptive Behaviour and Student Engagement: Are They Connected?

Is there a connection between disruptive behaviour and student engagement in the classroom? A lot of current research on this particular topic reveals that yes there is, and often it is quite a strong connection.

One research article which shows this strong connection between disruptive behaviour and student engagement is entitled, ‘Effects of Response Cards on Disruptive Behaviour and Academic Responding During Math Lessons by Fourth-Grade Urban Students’ written by Michael Lambert, Gwendolyn Heward, and Ya-yu Lo. Within the article, authors evaluate and explain the results of an experiment in which two separate 4th-grade urban education classrooms incorporated the use of student response cards into the daily math lessons (Lambert et al., 2006). The two classrooms selected to partake in this experiment were chosen because of the large number of students in each class who frequently displayed disruptive behaviour (Lambert et al., 2006). Additionally, many of the students who were involved in the study also had an extensive history of disciplinary issues in school (Lambert et al., 2006).

In the experiment, laminated response cards were given to every student so they could each write their own responses to questions posed by the teaching during math lessons (Lambert et al., 2006). This method of using response cards was then compared to the more traditional method of single-student responding. In single-student responding typically only one student has the opportunity to answer the question posed by the teacher, and the rest of the class is often left bored and unengaged, whereas the response-card method allows all students to respond and participate every single time (Lambert et al., 2006).

Findings within this study show that by incorporating response cards into the classroom, student engagement went up, disruptive behaviour went down, and student responding increased significantly (Lambert et al., 2006). In fact, results from this study show that every single student who participated in the study was observed to be less disruptive in the classroom when teachers incorporated response cards into the lesson (Lambert et al., 2006). By incorporating response cards into the lesson it allowed students to become active participants in their learning, which is what ultimately lead to higher levels of student engagement and lower levels of disruptive behaviour in the classroom. As a result of the huge shift in disruptive behaviour that was observed in this particular study, the authors suggest “the need for more effective instructional environments that actively engage urban youth in the learning process” (Lambert et al., 2006).

In contrast to some research that places student self-regulation techniques at the forefront of minimizing disruptive behaviour in the classroom this article emphasizes the importance of good teaching practices over self-regulated learning. In some of my experiences in elementary classrooms so far, I have been able to personally observe the effects of incorporating student response cards into a math lesson. Each time I have observed a teacher incorporate these cards into a lesson the outcome has been fantastic. I notice that student engagement appears to increase, student participation appears to increase, and instances of disruptive behaviour in the classroom are much lower.

Although I believe that the approach to minimizing disruptive behaviour in the classroom is a highly complex one, I think that good teaching practices, which aim to increase student engagement and participation, are an extremely important part of the puzzle.

References

Lambert, M. C., Cartledge, G., Heward, W. L., Lo, Y., & Koegel, R. L. (2006). Effects of response cards on disruptive behavior and academic responding during math lessons by fourth-grade urban students. Journal Of Positive Behavior Interventions, 8(2), 88-99.

Disruptive Behaviour: What is it and Why Study it?

Last week on my inquiry blog I discussed how SEL self-regulation techniques are a fantastic way to improve disruptive behaviour within the classroom. This week I want to take a step backwards and introduce what exactly ‘disruptive behaviour’ is, what it looks like in the classroom, and why it is such an important topic of study for both future and current educators.

The online Farlex Medical Dictionary defines disruptive behaviour as “a group of mental disorders of children and adolescents consisting of behaviour that violates social norms and is disruptive, often distressing others more than it does the person with the disorder. It includes conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder and is classified with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder” (2016). Although the above disorders are without a doubt linked to some cases of disruptive behaviour in the classroom, I think it is important to note that not all instances of disruptive behaviour are linked to a mental disorder. In fact, the majority of literature and research around disruptive behaviour in the classroom reflects a much broader and inclusive definition then that of the dictionary. For example, the education department at Clayton State University in Georgia defines disruptive behaviour as being any behaviour that hampers the ability of instructors to teach and students to learn. Alongside this definition, they also provide a list of common examples of disruptive behaviour within the classroom. This list is inclusive of, but not exclusive to:

- Eating in class

- Monopolizing classroom discussions

- Failing to respect the rights of other students to express their viewpoints

- Talking when the instructor or others are speaking

- Constant questions or interruptions which interfere with the instructor’s presentation

- Overt inattentiveness

- Creating excessive noise in the classroom

- Entering the class late or leaving early

- Use of cell phones in the classroom

- Inordinate or inappropriate demands for time or attention

- Poor personal hygiene (e.g., noticeably offensive body odor)

- Refusal to comply with direction

- Use of profanity or pejorative language

- Verbal abuse of instructor or other students (e.g., taunting, badgering, intimidation)

- Harassment of instructor or other students

- Threats to harm oneself or others

- Physical violence

Although some of these examples may be indicative of, or already in line with a properly diagnosed disruptive behavioural disorder, many are not. Thus, when examining disruptive behaviour in the classroom, I think it is extremely important to understand that not all disruptive behaviour is indicative of a mental disorder.

Why is disruptive behaviour in the classroom such an important area of study? Many studies show that disruptive behaviour, and proper management of these disruptive behaviours, are some of the biggest and most persistence problems facing educators in schools today. In fact, special-education professor Dr. M. Rosenberg and research associate L. Jackman, both of whom have conducted extensive research on disruptive behaviour and behaviour management in schools, maintain that disruptive behaviour in the classroom is the most troubling issue facing schools (2003). Additionally, their research has shown that many teachers spend as much time responding to disruptive behaviour within the classroom as they do teaching (Rosenberg & Jackman, 2003). As a result of my own experiences in the classroom, I can also attest to these findings. Disruptive behaviour in elementary school classrooms is a massive problem that needs to be examined further. Not only has current research shown that instances of disruptive behaviour in the classroom are on the rise, but it has also revealed that disruptive behaviour negatively impacts the individual exhibiting the behaviour, the teacher, and the entire classroom of students.

In a recent research paper outlining different educators’ experiences with disruptive behaviour in the classroom, author Kari Jacobsen discusses the huge increase in disruptive classroom behaviour over the recent years. Additionally, she discusses how this huge influx of disruptive behaviour has been proven to both negatively impact other students within the classroom and impair the classroom learning environment (Jacobsen, 2013). Although Jacobsen’s research recognizes the negative impact that disruptive behaviour can have on the entire classroom, she maintains that disruptive behaviour tendencies are most troublesome to the individual exhibiting the behaviour (2013). Some of the most common troublesome outcomes for the individual include low grades and higher school drop-out rates (Jacobsen, 2013). Thus, the importance of educators being able to detect and appropriately handle different situations of disruptive behaviour in the classroom is essential. For many children their teacher is the adult they see most often throughout the day; hence, this is why it is so important for educators to both educate themselves and understand the source of a child’s disruptive behaviour as they are often the first source of detection and early intervention in mental health disorders (Jacobsen, 2013).

References

Jacobsen, Kari. (2013). Educators’ Experiences with Disruptive Behavior in the Classroom: Master of Social Work Clinical Research Papers.

Rosenberg, M., Michael S Rosenberg, & Lori A Jackman. (2003). Intervention in school and clinic: Development, implementation, and sustainability of comprehensive school-wide behavior management systems Pro-Ed, 39(1), 10-21.

http://www.clayton.edu/Portals/5/DisruptiveClassroomBehavior.pdf

Disruptive Behaviour and Self Regulation: an SEL Approach

Stress, anxiety, restlessness, noise, poor nutrition, and lack of engagement are just a few of the factors that can trigger disruptive behaviour within the classroom. In an attempt to tackle this growing problem of disruptive behaviour in our schools many districts and teachers have adopted a social and emotional (SEL) approach to education that relies heavily on student self-regulation.

Self-regulation puts individual students in charge of their own learning and behaviour within the classroom. It is an approach in which teachers can help students become aware of their own behaviour, what their individual needs are, and what they can do for themselves to calm down and be productive in class. Thus, self-regulation refocuses the responsibilities to learn and behave appropriately back to the child. In a report published on the CBC News Canada website, Philosophy and Psychology Professor Stuart Shanker presents the idea that Canadian students do not know what it feels like to be calm anymore because there is far to much stimulation in their lives (2013). He argues that when a child’s brain enters a state of stress, anxiety, or general overload of some sort, that the child’s ‘thinking’ part of the brain shuts off and they can no longer hear what anyone is saying to them. This is why self-regulation and teaching our students how to self-regulate themselves is so important. Shanker suggests that the best way for a teacher to manage events of disruptive behaviour is to ‘de-escalate’ the situation, or in other words, to teach the child how to calm themselves down and get them to think again.

As noted by author Karin Wells, there are many ways that teachers can help teach and implement self-regulation within the classroom. Some of the easiest and most cost effective methods include incorporating more physical activity and movement into the school day, regular brain breaks or ‘engine breaks’, and providing students with the skills to be able to implement some of the above techniques by themselves without disrupting the rest of the class. Some additional self-regulation tools that are commonly found within classrooms are noise-cancelling headphones and small toys that students can play or fiddle with.

Learning about self-regulation and the different methods that can be used to help students learn how to self-regulate is something that I am very interested in learning more about. I have noticed that students who are both educated about self-regulation, and who have been given the tools or knowledge about how to self-regulate, appear to have far less behavioural problems in the classroom then students who do not know how to self-regulate. I believe that teaching students how to self-regulate is extremely important at any age, but exceptionally important during their intermediate years. For the most part I have noticed that as students progress from primary to intermediate, often their school days become more focused on academics and they are spending more and more time sitting in desks learning and less time actively moving around the classroom. This definitely may not be true for all classrooms and schools, but as for my experiences in elementary schools so far, it is what I most commonly observe. Many intermediate students struggle with stress, anxiety, hyperactivity, frustration, and emotional issues, and these are just a few of factors that can cause disruptive behaviour and impact learning. I believe that by educating intermediate students about self-regulation and by providing them with the proper skills and tools to properly do so, we as educators can help students to relax, de-stress, calm down, and in turn, improve classroom behaviour.

Reference

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/self-regulation-technique-helps-students-focus-in-class-1.2440688