In “playing” User Inyerface, an online “game” by Bagaar, you are meant to navigate to the end of a series of prompts designed to mimic typical web page/form filling mechanics, but twisted and satirized. I caught on to the shtick fairly quickly, as the opening page seemed wrong – the words on the buttons were not what you’d expect them to be, and the fine print text had underlines and what appeared to be hypertext in unexpected places.

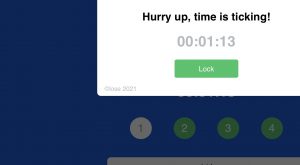

The feature that stumped me the most was a popup stating “the clock is ticking.” It wasn’t the time that rattled me, rather the only button or word that seemed to have any action was a button that locked the popup to the screen. The form that I was supposed to fill out was greyed-out behind the popup and inaccessible. I eventually navigated away from the game and reloaded. It wasn’t until my third attempt and encounter with the popup that I realised the copyright fine print line actually used the © symbol as the letter “c” in the word “close.” Once past this hurdle, I was able to get through the proceeding steps mostly uninhibited.

I was reminded of Bolter (2001) in this use of misleading iconography. I criticised Bolter back in week 6 for having an over-the-top disdain for imagery and graphical elements co-existing with (and pushing out) text, bordering on paranoia. I think he would love this “game.” On reflection, the strategy I employed was to read the text literally and try to ignore any visual cues that would normally lead people to navigate without actually reading (e.g. graphic design elements, colours, shapes, highlights, buttons, etc.) – typically, for example, the “next” button is green, or is in the bottom right corner with an arrow pointing to the right; a selected option is highlighted in a bold colour; and the cursor changes form when hovering over hypertext or buttons. These are features we take for granted and the game plays on this. A similar concept had occurred to me before, but not the realization that is the visual cues that influence our behaviour. Perhaps Bolter was right to be worried. Reading and writing are artificial – human creations – and evolution wired our brains for visual preeminence.

The utilitarian application of such a “design flaw” in the human architecture is being harnessed by advertisers. While this is not news to anyone in the third decade of the 21st century, it’s study is nevertheless of great importance. Brignull (2011) outlines these practices and the deeper psychology being taken advantage of, as does Thaler’s studies of influencing behaviour through establishing “defaults.”

Final Thoughts:

Where does it lead? Following the insights of Harris (2017) and Tufekci (2017), my thoughts go to environmental equilibrium. Just as it’s taken the past several decades for governments and corporations to acknowledge the reality of human-caused climate change and realize that exponential economic growth through resource extraction isn’t infinitely sustainable, I wonder if the companies whose practice is to harness the hunger for misinformation to obtain more clicks will have to find a pendulum-swing-point and equilibrate; if Facebook pushes it’s far-right or extreme left users too far, it could cause such political instability as to jeopardize its own existence. If the ethics of behavioural economics and consumer psychology don’t motivate corporations to change of their own volition or governments to legislate them to more ethical practices, hopefully they will act when they see the potential implications of “social climate change.”

References

- Bolter, J. D. (2001). Writing space: Computers, hypertext, and the remediation of print (2nd ed.). Mahwah, N.J: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. doi:10.4324/9781410600110

- Brignull, H. (2011). Dark Patterns: Deception vs. Honesty in UI Design. Interaction Design, Usability, 338.

- Decision Lab – Richard Thaler. (Retrieved 20 March 2021) https://thedecisionlab.com/thinkers/economics/richard-thaler/

- Harris, T. (2017). How a handful of tech companies control billions of minds every day. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/tristan_harris_the_manipulative_tricks_tech_companies_use_to_capture_your_attention?language=en

- Tufekci, Z. (2017). We’re building a dystopia just to make people click on ads. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/zeynep_tufekci_we_re_building_a_dystopia_just_to_make_people_click_on_ads?language=en