Gunless, not directed or written by Gross but featuring him playing an American desperado, the Montana Kid, seems an odd inverted casting for this actor who has made a career out of playing hyper-Canadians, but the film fits with the logic of his work as noted by Aniko Bodroghkozy who writes about the early Gross television vehicle, Due South

What Canadians do with their popular culture is to work through imaginatively their relations with their southern neighbours. If as Seymour Martin Lipset observes, “Canadians have tended to define themselves not in terms of their own national history and traditions but by reference to what they are not: Americans,” then their hardy appetite for American cultural products makes a great deal of sense. As “not-Americans,” Canadians are the ultimate anti-Americans.” (572)

Within the framework of a Western gone “North,” Gunless aims for that notion that Americans are explicitly racists gunslingers while peace loving Canadians are simultaneously fascinated and revolted by American culture. The film’s opening sequence that presents the Kid entering the Canadian frontier town of Barclay’s Bush

with a noose around his neck, tied backwards to his horse, and badly beaten immediately establishes that the Kid is a wild American who does not grasp the civil Canadian “rules of engagement” do not allow for gun fighting. This character is not an imperial heroic John Wayne like cowboy, but a cartoon figure of the American hero brought low. In this opening scene, the first lines of the script are uttered by the Kid who roped to his horse addresses a young Chinese girl, Adell (Melody Choi) dressed in pioneer costume with this line, “you-ee, speak-ee English?” [sic]. As viewers, we share the Kid’s upside down perspective on this child, who placing her hands on her hips, and asks “do you? You stink!” The “foreigner” in this narrative is clearly the Kid while the Canadian in this upside down perspective is this Asian-Canadian child. The Kid wears a “Chinese coat” throughout the middle part of this narrative as he confirms his outsider status. This status by the third act of the film shifts as he begins to wear proper “cowboy attire” and thus become more white, less exotic, and a bit more, dare I say, Canadian.

Gunless does not speak of the Head Tax or Exclusion Act (1885-1923), which prevented Asian men from bringing their families to Canada, but imagines this Chinese family is free to prosper in Barclay Bush running a laundry service for whites. Despite this gesture to Canada as an inclusive multicultural pastoral where racialized Others know their occupation, the narrative tends to focus on the Anglo-white characters as Canadians with the sole exception of the Chinese family and a French Canadian merchant who shares a business with a British merchant (an apt metaphor for Confederation’s uneasy alliance between French and English values). The Chinese family is uninvolved in various scenes where white Canadians discuss and dispute the Kid and by extension America’s penchant for gun violence. In fact, the Asian-Canadian characters’ role in this narrative is to be the passive victims threatened by the American bounty hunters. In the climax, the American bounty hunter Ben Cutler (Keith Callum Renee) prepares to hang the passive and speechless Mr. Kwan (Chang Tseng). Cutler makes a rhetorically tortured speech that would make George Bush blush, “I will not abide anyone’s purposeful undermining of our adventure, so I will start with the Chinamen [sic] and work through his family one by one” until the town hands over the Kid. Kwan and the other Asian characters are incapable of offering anything but passive resistance. It is the white members of the town who take up guns and resist this violence with the threat of more violence. This inability to imagine Asian character having agency or being able to resist the imperial American forces is consistent with the view that only white Canadians, as true citizens, can secure Canadian identity and thus save Kwan with the help of the Kid who has uneasily assimilated Canadian values. The resolution permits the RCMP to restore order as they send the bounty hunters south of the border, but the climax rests with the notion of Canadians defending themselves with guns against invaders with a little help from the Kid, who is the embodiment of masculinity as opposed to the quirky white Canadian males.

Gunless flirts with the notion that Canadians can be “bad” to immigrants in a scene where the Kid is roughed up by a group of RCMP constables who “discriminate” against him for being an American outlaw. This conflict is quickly resolved with the proper higher authority Corporal Jonathan Kent (Dustin Milligan), who intervenes and issues an apology for his troops to the Kid. As a suitor for the widow Jane Taylor (Sienna Guillory), Kent’s should wish his constables dispose of his rival the Kid, but Kent upholds a code of honour and the notion of the RCMP as part of a benevolent and professional police force that may occasionally be spoiled by “a few bad apples.” Perhaps this scene implicitly reprises the bad press the RCMP received with the “death” of Polish immigrant Robert Dziekanski at Vancouver International airport on October 14, 2007 via a Taser (and not a gun).

Despite the film’s Western setting, it resonates with current contested notions of Canadian identity, and thus I present the following conclusions:

- As Canada’s military continues to help occupy Afghanistan, a film like Gunless helps express the idea that white Anglo Canadians are by and large not prone to violence but are bound by a duty to protect the helpless, who are all too often incapable of helping themselves.

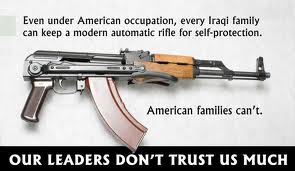

- In September 2010, a private members bill failed to dismantle the long gun registry, but as CTV News reports Prime Minister Harper was undaunted by this setback: “’With the vote tonight its abolition is closer than it has ever been,’ Harper told reporters immediately after the vote. ‘The people of the regions of this country are never going to accept being treated like criminals and we will continue our efforts until this registry is finally abolished.’” Gunless’s conclusion, which sees white Canadians “bearing arms” with the Montana Kid to repel ruthless American bounty hunters, seems to tug at the Canadian identity as a kinder, gentler sensibility and to insist the Canadian national identity may entertain pacifism, but the “duty to protect” supersedes those humanist notions. Gunless’s strategic nostalgia tugs at the notion that “historically “ white invader-settlers regulated their own gun use, and thus contemporary Canadians may not need a long gun registry.

Works Cited

Ahluwalia, Pal “When Does a Settler Become a Native? Citizenship and Identity in a Settler Society.” Pretexts: Literary and Cultural Studies 10.1 (2001): 64-73. Print.

Bodroghkozy, Aniko “As Canadian as Possible . . . : Anglo-Canadian Popular Culture and the American Other.” Hop on Pop: The Politics and Pleasures of Popular Culture. Eds. Henry Jenkins, Tara McPherson, and Jane Shattuc. Durham & London: Duke UP, 2002. 566-589. Print.

Brydon, Diana. “Introduction: Reading Postcoloniality, Reading Canada (Introduction to Issue of Essays on Canadian Writing Entitled Testing the Limits: Postcolonial Theories & Canadian Literature).” Essays on Canadian Writing. 56.1 (1995). Online.

Coleman, Daniel. White Civilities: The Literary Project of English Canada. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2006. Print.

“House of Commons Votes to Save Long-gun Registry.” CTV.ca 22 Sept. 2010. Web.

http://www.ctv.ca/CTVNews/TopStories/20100922/gun-registry-vote-100922/.