4. Identify and discuss two of King’s “acts of narrative decolonization.” Please read the following quote to assist you with your answer. The lives of King’s characters are entangled in and informed by both the colonial legacy in the Americas and the narratives that enact and enable colonial domination. King begins to extricate his characters’ lives from the domination of the invader’s discourses by weaving their stories into both Native American oral traditions and into revisions of some of the most damaging narratives of domination and conquest: European American origin stories and national myths, canonical literary texts, and popular culture texts such as John Wayne films.These revisions are acts of narrative decolonization. James Cox. “All This Water Imagery Must Mean Something.” Canadian Literature 161-162 (1999). Web April 04/2013.

In reading “Green Grass, Running Water” by Thomas King, I found two key examples that attempted to exemplify an ‘act of decolonization’. I have divided my answers into two sections which include the interaction of Old Woman and the young man walking on water

1.) The interaction of Old Woman and the Young Man Walking On Water

King’s narration of the interaction between Old Woman and what appears to be a “first nations” version of Jesus Christ (Cox) is an example of how Thomas King attempts to narrate an act of decolonization from the First Nations perspective that challenges settler colonial ideology. For example, when the Old Woman falls out of the sky and into the water, she meets the Young Man Walking On Water who mentions that he is looking for a boat, and when the Old Woman spots a boat and asks if this boat is the one he is looking for, he says “not if you saw it first” (King 349). This narration challenges the concept of storytelling; once a story has been told, it can not be revised nor taken back. Moreover, The Old Woman spotting the boat, singing the song to relax the waves and King’s narration of the Old Woman attempting to take credit for being the ‘savior’ of the young men on the boat attempts to challenge the European narrative by narrating the Old Woman as a ‘savior’ and challenging the ‘rules’ of those who consider themselves ‘superior’ (351). King attempts to challenge the rule of storytelling by implementing a character that interacts with and challenges the ‘man walking on water’; which is interpreted as an act of narrative decolonization through challenging dominating colonial ideologies associated with religious icons (Jesus Christ) through re-creating a ‘savior’ character through the narration of the interactions between the Old Woman and the man walking on water.

2.) First Woman & Ahdamn (Page. 68, 139)

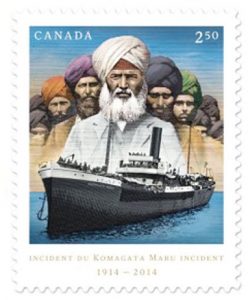

King challenges the colonization of the First Nations when he is narrating the First Woman’s interaction with GOD. For example, First Woman doesn’t seem to be phased by GOD when he states his land ownership to the garden and that she should not be eating his nice red apples as it he considers a violation of his property, which challenges his land claim (68). King’s narration of First Woman as ‘invading’ into GODS land which is exemplified by First Woman discrediting GODS claim to the land ownership and violating the ‘Christian Rules’ supports the acts of narrative decolonization by narrating First Woman as the ‘invader’ into foreign land.

The narration of First Woman and Ahdamn’s reaction to getting arrested and First Woman’s response after she was notified that she was arrested for “Being Indian” (King 72) illustrates a sarcastic voice that challenges the power of authority. Moreover, the emphasis placed on how “it looks like a very nice day for one, too” (King 72) when reacting to the arrest attempts to disable the power of colonial settlers through King’s narration of an unexpected positive reaction to getting arrested which is expressed in a humorous way when the experience of getting arrested is compared by Ahdamn as an ‘adventure’ (72). The positive spin introduced by King when narrating the positive reactions to getting arrested attempts to change the damaging narratives of the colonial conquest and domination (Cox), which supports the acts of narrative decolonization by disrupting western narratives of colonization.

Works Cited

“Bible Gateway Passage: Matthew 14:22-33 – New International Version.” Bible Gateway. Biblica, Inc, n.d. Web. 01 July 2016.

Cox, James H. “All This Water Imagery Must Mean Something”: Thomas King’s Revisions Of Narratives Of Domination And Conquest In “Green Grass, Running Water.” American Indian Quarterly 24.2 (2000): 219-246. Education Source. Web. 30 June 2016.

Gray, Robin R.R. Reconciliation_wordle_2.png. 25 Mar. 2014. Simon Fraser University. SFU.ca. Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage, 25 Mar. 2015. Web. 30 June 2016.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

Marshall, Tabitha. “Oka Crisis.” The Canadian Encyclopedia. CDNENCYCLOPEDIA, 07 Nov. 2013. Web. 01 July 2016.