Hangul is ‘Honey-Jam’! – 한글은 꿀잼!

By Strang Burton and Stanley Nam

Introduction

In the 15th century, King Sejong the Great of Korea decided to reform Korean writing.

Up until that time, Koreans had used Chinese characters—sometimes writing in Chinese, other times re-purposing the Chinese characters to represent Korean words and sounds. Either way, learning to read and write in Korea before Sejong meant years of work mastering thousands of characters.

But Sejong wanted something better. Specifically, he wanted a system of symbols so simple that “a wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over, and a stupid man can learn them in the space of ten days.” And he got it!

The resulting alphabet, which Sejong and a royal think-tank put together from scratch, is called hangul—and it is one of the simplest and most elegantly designed writing systems ever created.

The rest of this post is a short introduction to the hangul system. It won’t teach you the full system, but it will lead you through some examples that illustrate how hangul works, followed by some discussion of the underlying design features that make it such a uniquely effective writing system.

Continue reading

Assassin – Hashish

The word ‘assassin’ comes from the nickname for a sect of fanatical 13th century professional killers, based on their supposedly heavy use of hashish. The story goes like this…

Birth of the Nizaris

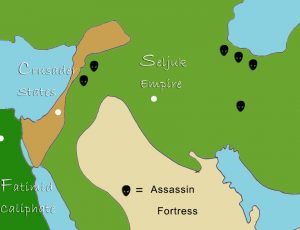

Back around 1200A.D., Middle Eastern politics revolved around ongoing conflicts between three major powers:

- A ‘Fatimid’ Caliphate (Ismaili Shiite, centered in Cairo)

- A ‘Seljuk’ Empire (Sunni, centered in Baghdad)

- Crusader States (Christian, centered in Jerusalem)

Out of this turmoil, there emerged a small but (at the time) very violent new sect, calling themselves the ‘Nizaris’—a group that was simultaneously opposed to all three empires.

Killer Niche

How does one little sect fight three big powers? You can’t do it in open battle, of course. So instead, the Nizaris decided to focus on a niche: terrifying and intimidating their opponents through targeted political killings.

Basing themselves in a series of impregnable fortresses in Iran and Syria, the group developed squadrons of professional killers, and sent them out on secret missions to ‘deep-six’ such high-profile victims as:

- The King of Jerusalem

- The Count of Tripoli

- The Crown Prince of Tripoli

- A Grand Vizier

- At least two Caliphs

And hundreds, possibly thousands, more. Every killing was done with a special dagger. Every mission was a suicide mission. And in this way the Nizaris developed an outstanding reputation as world-class professional killers: able to take out anyone, anywhere, anytime. Scary dudes!

Hashish, anyone?

Oddly, given their amazing discipline and martial skill, the 13th century Nizaris got another reputation, too: as heavy users of hashish. There are at least two competing stories about why:

- Some sources say the killers would always get high before going on a mission—something not unheard of, of course, in modern warfare either.

- Other sources say that the Nizaris used drugs as part of their initiation rituals, triggering hallucinations of paradise in the minds of the trainees; having glimpsed paradise, the story goes, the soldiers were eager and willing to die on a mission.

The stories may not even have been true, but they became wide-spread, and ‘hashish-users’ became a common nickname for the group—so that after a political killing people would say ‘Oh, those hashish-users have struck again!’

Arabic origins

The Arabic word for hashish is pronounced /ḥaʃiʃ/ ( the /h/ has a small dot under it in the phonetic representation, to indicate that it has some closure in the pharynx, i.e. in the throat).

The plural form for this class of noun is –in, so the plural becomes /ḥaʃiʃin/.

The latter can be used to mean ‘hashish users’ or ‘hashish eaters’, and it is this word that the medieval Europeans mangled—apparently not realizing that it was a plural—to make the singular English noun assassin. (A similar ‘mistake’ happened centuries later when we borrowed pirogi from Russian; in Russian, Polish, and Ukrainian, pirogi is the plural form, but in English we now talk about ‘one pirogi‘.)

In the Islamic world /ḥaʃiʃin/ was never more than a nickname for the Ismaili Nizaris (if even that); but in Europe ‘assassins’ became a standard medieval name for the whole group—you will even see areas marked ‘Land of the Assassins’ on many medieval maps of the Middle East. Speakers in Europe then generalized the word to the modern sense of ‘assassin’ as anyone who carries out targeted political killings.

The modern Nizaris

The Ismaili Nizari religious group still exists, but you have no reason to fear them today: the group long ago mellowed out, ‘closed the veil’ on their program of targeted killing, and converted to a more mainstream branch of Islam. Whew!

In fact, the modern leader of the group—a jet-setting millionaire with the title of Aga Khan—is actually devoted to social welfare, and runs all kinds of awesome programs. You probably still shouldn’t mess with the guy, though!

Sources

-

-

- Esposito, John L. The Oxford History of Islam. New York, NY: Oxford UP, 1999. Print.

- Haag, Michael. The Templars: the History and the Myth. New York And London: Harper, 2009. Print.

- “Oxford Dictionary of English.”, Second Edition, Revised, Soanes, Catherine and Angus Stevenson eds.

- “Oxford English Dictionary.”, Oxford University Press

- Online Etymology Dictionary

- Wintle, Justin. The Rough Guide History of Islam. London: Rough Guides, 2003. Print.

-

Audio is by Ms. Wafa Al-Ali, thanks so much. All media for this post is original to Dexterous Tongue.