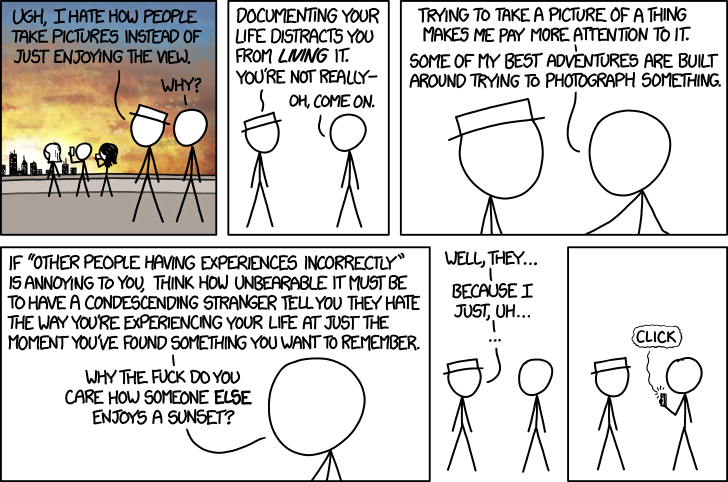

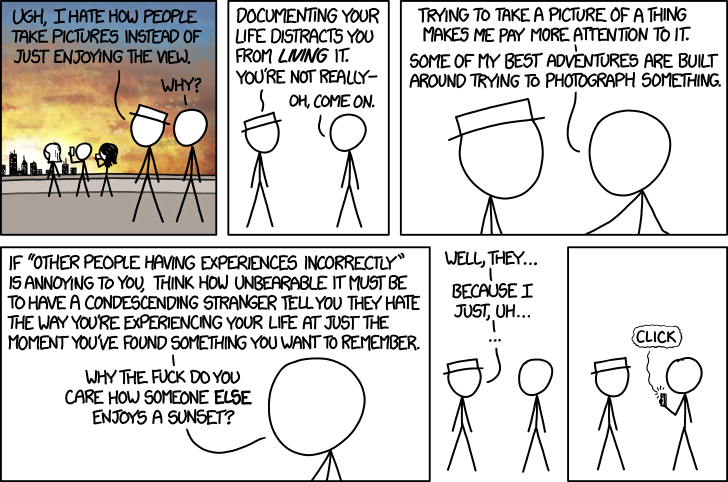

Question 7:

This comic for me, conveys many of the ways that technology augments and mediates cultural production Much like high art can only exist by the denigration and dismissal of say, graffiti, technological advances in social media are at risk of being constructed as frivolous or arbitrary in comparison to ‘frontline’ activism. In fact, many cultural critics have leveled social media as a new means of faux-activism or “slacktivism”. The dangers of painting all social media or technological orality with such a broad brush is that it begins to erase, undo, and minimize the ways in which these moments of technological augmentation function both as the signifier and signified of activism. Idle No More and the Indigenous Nationhood Movement have used Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, and Tumblr to tell a particular stream of narratives about land-rights, histories and futurities. This polyphony of stories around indigeneity then begin to disrupt or decolonize the settler colonial belief that aboriginal peoples are one singular and knowable group. In such a way, the ‘freedom’ granted by the Internet, and the low-barrier means of publishing (or micro-publishing) without going through review panels, publishing houses, editors, and critics allow grassroots organizations to reach a wide and diverse audience.

I am struck by a recent feminist, anti-racist interrogation of “selfies”—a self-taken, self-published photo of oneself on social media platforms which challenged the idea that those taking the photos are narcissistic. Indeed, the black feminist writer Dulce De Leche tweeted late in 2013 that “selfies are the only place [she] see[s] women like [her]” (2013). This opens up a radical reimagining of the technology of image acting as oration—we hear and see stories of representation through image. We can of course, extrapolate this into the ways in which people used the hashtag “#feministselfie” coined by De Leche through other social media ventures as the permeability of image into text—picture into story. Once more, the oft-denigrated, social media ventures of self-representation can begin to be read as doing what some of the best stories do; looking the oppressor in the eye and saying we are still here.

What these oralities are doing across their business of story telling is pointing to an imaginative future, a possibility, a point B that may not ever exist in a way that we can expect (or suspect). The late queer theorist José Muñoz positions “[q]ueerness [as] that thing that lets us feel that this world is not enough, that indeed something is missing”(1) (2010) . He likens this idea of something missing, of speculating and imagining to fill in this missing piece as ‘futurity’. In this way, I think examining the hyperlink as both a concrete and physical actor in technological pieces like blog posts, and as a metaphor for imag(in)ing indigenous existence is a fruitful exercise. First, what it does as a physical manifestation in blog posts, is lend itself to intertextuality. It does what physical text can only attempt to do in citations and footnotes—pushes us onto more and more, never yielding, and always hastening. The hyperlink in blog posts (or youtube posts, tweets, etc.) makes a community around text, invites other voices in, and indeed, invites us, the reader, in to be part of it. It is at once an education as it is a beckoning. This need not simply be tied to the idea of academia, but websites like Idle No More’s begin to push us to Facebook events of very real ‘front-line’ activisms, petitions, news sites on land claims and settlements. The hyperlink has teeth to it. It is about more. This brings us to the metaphor of the hyperlink in orations. There it sits, royal blue and expecting, asking us to click, to continue to explore. The hyperlink before-clicked then, can be read as an imaginative speculation—it could take us anywhere, bring us to anything, perhaps even download a .pdf uninvited (ugh, the worst). It creates its own fictive network of possibility and desire. The moment between the clicking of the link and the revealing of the information it conceals is of all the importance in this practice of storytelling, for it is in this moment that the reader becomes implicated in the story. Both being asked to imagine where to by the hyperlink, and the moment of being invited to here by the eventual location of the text; the text becomes extraordinary.

J. Edward Chamberlin positions in his book If This is Your Land, Where are Your Stories (2004) that stories tell us “how to live, and sometimes how to die” (4). If we are to take this as a leading point in reading his work, then, we are given a sense of futurity in-text. Stories don’t just point us to a sense of where we came from, they point to a possible ending point as well. In this sense, stories operate as hypertext—never quite arrived, but always in a state of arriving. This is a peculiar state to be in, this business of storytelling. Chamberlin navigates this peculiarity well in his exploration of infinity, stating that it is “’a place where things happen that don’t.’ That’s the place of story and song” (1678). Infinity then, is as much of a hypertext as the story is. Each represents endless possibilities, much like orations, and their various interpretations expel.

I am struck by the possibility that story and hypertext represent a place marker to record histories as well as to imagine a future of say, indigenous sovereignty. These moments in time come with complications, however. Thinking through the benefits of ‘publisherless’ orations—Tweets, Twitter, Tumblr posts, etc. poses a graver question. Who is enabling these posts to exist free-of-charge? What are the implications, particularly for groups like Idle No More of publishing or orating on a free website like Twitter which sell user-generated information to advertising companies? Is there a marketable type of activism? The theorist Lauren Berlant points to this type of neoliberal off-loading as a “cruel optimism” (13). A hyperlink if you will, whose limitless or ‘eternal’ futurity is bound to and by capitalism (and I will venture forth that it is also bound to and by colonialism—after all, what types of mercantilism were introduced and proliferated from ‘contact’?).

Works Cited

Berlant, Lauren Gail. Cruel optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011. Print.

Berlant, Lauren. “Supervalent Thought.” Supervalent Thought. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Jan. 2014.

Chamberlin, J. Edward. If this is your land, where are your stories?: finding common ground. Random House Digital, Inc., 2010. E-book.

De Leche, Dulce (Bad_dominicana). “selfies are the only place I see women like me. unlike whites, I dont have entire industries made in my image. #feministselfie” 21 Nov 2013, 10:49 a.m. Tweet.

Idle No More. “The Movement.” Idle No More, n.d. Web. 07 Jan. 2014.

Indigenous Nationhood Movement. “Statement of Principles.” (2013): n. pag. Indigenous Nationhood Movement RSS2. Web. 17 Jan. 2014.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising utopia: The then and there of queer futurity. NYU Press, 2010. Print.

Munroe, Randall. “Photos.” Cartoon. XKCD. XKCD, 8 Jan. 2014. Web.

Rotman, Dana, et al. “From slacktivism to activism: participatory culture in the age of social media.” CHI’11 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, 2011. Web.