It’s been a long time since I took an introduction to networks course, but I do recall this what we’re seeing in here Palladio is a bipartite graph. What does that mean for our purposes? It means every edge connects a curator to a track. There are no edges between tracks, nor are there any edges between curators.

The network graph produced by Palladio demonstrates a few different aspects of our selections. With each person selecting 10 tracks out of only 27 there is, unsurprisingly, a high degree of connectivity. But first…

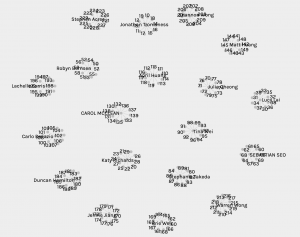

It’s nice to start an analysis like this by breaking it down and taking a step back. By setting the Source to “generated” and the Target to “label_1”, we can see each curator and their 10 track selections (at least, the track IDs presumably). Though I can’t identify a way to have the track names displayed in this view, it at least provides us with a first step. We see each curator with their ten track selections and, at a glance, they all look relatively varied.

Now let’s jump to the whole view of the graph.

From this view, we can see how richly interconnected our selections are. As I mentioned earlier, this isn’t unsurprising – with such a small tracklisting to choose from, the graph is bound to be dense with overlapping edges and highly trafficked nodes. Immediately though, we can see some outliers. Tracks such as Track 22: Panpipes (Solomon Islands) and Track 16: Rite of Spring (Sacrificial Dance), were each only selected by single curators, with only a single edge connecting them to the graph.

There are several other tracks on the periphery, with only one or two edges exiting them. And in the middle we see the more popular, highly connected tracks. From this birds-eye-view of the network graph, its difficult to really derive any insight of value. Besides a cursory look at which tracks were especially popular or unpopular in the selection quiz, there isn’t much more information being conveyed.

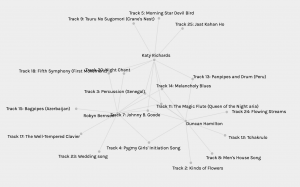

Let’s look next at the groupings.

Here is modularity_class 5. There are three curators in this group, including myself. These three curators have been grouped together based on our overlapping node (track) selections, it seems. Tracks 11, 14, 7, and 3 were selected by all of us.

What is clearly missing though, is why? I might have selected Johnny B. Goode because of that one scene in Back to the Future. Katy might have chosen it because it’s one of the few tracks with a guitar, and Robyn might have chosen it because she selected each track by throwing darts a board in the dark (I think we can assume she didn’t, but she might have!). The real reason I chose Johnny B. Goode is because Alan Lomax and Carl Sagan both hated it, which I thought was a funny anecdote.

None of this nuance is captured in the network graph. So what does this grouping say about “modularity_class 5”? Without more context, it doesn’t say anything. We can’t identify shared characteristics, tendencies, or personal taste from this network. The importance of context is touched on by Dr. Smith Rumsey in her lecture “Digital Memory: What can we afford to lose?”.

We actually don’t know the value of anything until way in the future, because its actual meaning is determined by events and context that we don’t know about.

Without context, this network graph’s value is limited. There is no indication why track selections or omissions were made at all. The issue is that so much of modern advertising, political decision-making, and algorithmic curation is based on data conceptually similar to this network graph.

What ads were clicked, which videos resulted in the longest watch-time, which individuals who donate to candidate X purchase product Y? From a broad enough perspective, these are all ultimately bipartite graphs. Clearly, they work to a certain extent. With enough data, a company like Youtube can pretty accurately say that individuals who watch a certain video are likely to also watch another certain video. And their motivation to get it right is high – as the more videos people watch, the more ads Youtube can sell.

But this form of data is contextually bereft. I might watch something and be intrigued, while someone else may watch a video and be disgusted – either way, that video’s node now has an edge to each of us. All that matters is that I watch the ads.

It feels to a certain extent that the modern web is slowly having its context eroded. Grassroots, community-driven website and forums have been overtaken and absorbed by corporate controlled, walled-garden products, who’s interest is only in creating value for shareholders. Personal blogs are few and far between these days. Traditional message-boards as well. In their stead are algorithmically curated social media apps and Discord chatrooms. These replacements feel so ephemeral in comparison to the originals, where content is simply churned through, never to be seen again.

We’ve all had instances of googling a problem and finding a solution in a random message board from 2001 – will that ever happen again, with so much of our contextual knowledge hidden behind conversion-hungry algorithms?

References

Brown University (Director). (2017, July 11). Abby Smith Rumsey: “Digital Memory: What Can We Afford to Lose?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FBrahqg9ZMc

Leave a Reply