It is 4:30am in Addis, and I am listening to the prayers broadcast across the city as I write. We have been here for less than three days, and yet it seems much longer because we have been very busy. Yesterday we began with a meeting with Dean Tirussew Kidanmariam Tefarra of the Faculty of Education at Addis Ababa University (AAU). We spoke of the main purpose of our visit: possibilities for parallel research projects at AAU and UBC that might allow for scholarly exchange among faculty and students at both institutions. We presented one possible methodological approach for an initial project: a form of pictorial ethnography whereby learners use digital cameras to document their formal and informal learning settings and have conversations with researchers about the significance of the images they have captured. Especially among young children and in multilingual settings where language may be a barrier, this has proved a useful method for garnering understanding as to how children perceive, and what they find important within, their learning environments. (I’ll add references to this post when I have better connectivity.) Dean Tirussew was keen on this project, particularly pointing out the benefits of such a project for teacher education, and anticipated that a number of graduate students at AAU might be interested in such work. We hope to arrange a meeting with such students when we return from Bahir Dar. At the close of the meeting we provided two digital cameras for use by AAU graduate students or faculty who wish to carry out research employing this method. When the AAU researchers have identified research settings, we will invite interested graduate students at UBC to carry out similar research in a parallel setting in British Columbia and set up a means of digital communication between sites. The collective data will provide a catalyst for conversations among researchers at both sites, for mentorship of students, for furthering of understanding of literacy practices in diverse contexts, and for building of research capacity at AAU, all key goals of ECERC.

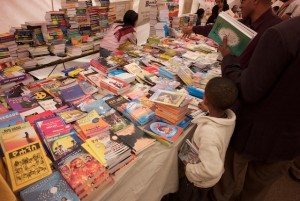

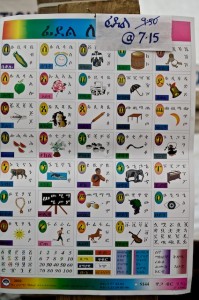

Following our meeting we rejoined Shirley Lewis (see yesterday’s post) at AAU to walk through a book fair and meet with key players in the Ethiopian publishing industry. We looked at collections of books for children in Amharic and discussed incentives that have been put in place to encourage the writing of children’s books in Amharic (e.g., writing prizes). Here the main language of instruction up to grade six is Amharic (thereafter it is English), and therefore it is important that a corpus of context-specific early literacy books in Amharic is established and made available widely. Ideally, libraries would be filled with such books rather than early literacy books in English that have been donated from abroad. (This is not to say that such donations are not important; it is merely that such donated volumes frequently depict foreign youth undertaking activities and dealing with issues that are far removed from the local context, which evidently has implications for reader reception in Ethiopia.)

The local publishing industry is fledgling, however, and while there is great demand for Amheric books it is hard for publishers to make a profit in part because of the expense of paper and other production costs, and in part because those who most need the books are not in a position to pay for them. The option of open access digital distribution (via online or offline means) would seem an important strategy to pursue, and both Jeff and I have been keen to discuss the possibilities, and yet those in the publishing industry and those working to establish libraries and reading rooms understandably remain sceptical. When I raised the possibilities with Shirley Lewis, citing an example of a joint digital library initiative of School District 62 in Victoria, BC and the Electronic Textual Cultures Laboratory at the University of Victoria, she expressed interest and spoke of a disk she purchased for 10 Birr containing 4000 texts in the public domain harvested from sites such as Project Gutenberg. This is an ideal resource for sites with computers and without connectivity, and she stated that her Ethiopian librarian contacts invariably want copies if she has them on hand. And yet, how might distribution in this form be balanced with the needs of the fledgling local publishing industry? And to what extent do the costs of hardware and maintenance — even if connectivity is not required — outweigh the benefits?

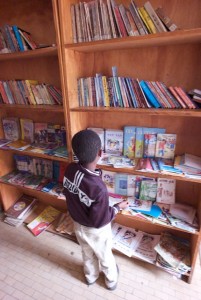

Alemseged, the school library program director with Ethiopia Reads, spoke candidly of such problems later in the day when we visited the Shola Children’s Library, likely the best-stocked public library for children in Addis and a safe oasis from the bustle of the streets with a modest collection of a few thousand donated English volumes as w ell as some newer volumes in Amharic. It was filled with children on the Saturday we visited, who read at desks in the building (a converted home), and in a grassed courtyard overhung with a large Hibiscus tree brimming with brilliant fuchsia blossoms. The ECBC sponsors a hygine program in the same location so that those who have need may also bathe, have their clothing washed, and get a haircut. There were many children waiting for these services when we visited.

Ethiopia Reads is doing wonderful work — considering the needs of young learners holistically, with understanding that health and safety are necessary precursors of intellectual engagement; and yet the need is far beyond what they are able to provide. As intimated earlier, many of the donated English volumes with which their libraries are stocked are donated from culls of North American libraries (the solitary book on Canada in the ECRC, for example, was published in 1987 and obviously contained much outdated information, which is certainly why it was culled from the California public library from which it hailed). So much of the English collection needs updating, local content, as ever, is essential, and in all of this it is important to explore strategies for making digital resources available in a manner that is sensitive to the local publishing industry. (As to the last, Shirley intimated that a similar difficulty faces the fledgling textile industry: donations of clothing from abroad, while of immediate benefit for the poor, may undermine the work of local clothing factories and in so doing perpetuate the cycle of poverty by putting locals out of work.)

Finally, we visited Sabahar, a local silk factory run by Kathy Marshall, a Canadian whose goal is to provide reliable employment for locals, mostly women. She has imported silk worms from Northern India. Her staff raise the worms, harvest and spin the silk. Dyes are made from local plants and the silk is woven into beautiful scarves on site which she has begun in the last few years to export around the world. It has taken years to build the business, and it barely breaks even; however, Kathy emphasizes that the business is a huge success in that she is now employing 50-60 local workers on an ongoing basis.

One reply on “The Challenges of Knowledge Access”

Thank you, Teresa, for this very helpful commentary on your discussions. I look forward to reading more as you have opportunity to post, and of course to Jeff’s images.

In thinking about the key publishing policy dilemma you’ve raised with respect to digital or hard copy, I wonder if you have you been able to find out much yet about the available level and cost of hardware support?