8 March. Monday. Marlene and I have an appointment to see a local school today, but it is not until 2:30pm, and so she will write this morning and I will take one last opportunity to get back up the mountains. Today Destow and I hike alone because Chloe and Alex have returned to Addis. We leave before 7:00am because the plan is for a 32km round-trip to a remote rock-hewn church at over 3400 meters. We’ll need to climb well over 700 meters on the 16 km path out. We have only seven hours, and so Destow sets a relentless pace that leaves me gasping on the steeper slopes.

He is well able to do this, for he spent two years running 20km — each way — to high school. A marathon five days a week. He tells me it took him about five hours a day to make the journey — three hours out and two hours back. The way there, he says by way of explanation, was mostly uphill. Destow’s family home is in the country on the flats well below Lalibela. Until grade three he was able to attend a local school. Thereafter he ran 7km to the junior school every day. And back. When he elected to go on with his education past grade nine he had no option but to run to the nearest high school 20km away.

Before 8:00am we pass through a town about two km beyond Lalibela. We are silently joined there by a young boy who looks to be five or six to me, but who later informs us he is eight. He has to jog to keep up and does so for at least three km going up a steep, rock-strewn path. He proudly carries a set of new plastic shoes and wears another on his feet. Destow tells me the boy lives in the mountain village higher up the path. Apparently he was sent by his family at daybreak to journey on his own 5 or 6 km down to Lalibela to fetch shoes for himself and another member of his family. I think of my own son, only a year older, who would not venture a block away from home on his own.

Our young companion leaves us at the next village and we continue upwards over the shoulder of the mountain. As the trail starts to level out we are met by a robed priest journeying the other way. Destow tells him we have come to visit his church and so he turns to join us, stopping periodically to bless the few people we meet coming down the mountain.

The church is remote and impressive–apparently dating to the 12th century. It is hewn from sandstone and so has suffered through time. It is partially collapsed and has been repaired — is now protected by a roof of corrugated iron perched on Eucalyptus scaffolding. The guard’s son is terrified of me and he hides in his father’s robe. I am the first foreigner to this region in months, so Destow tells me. The distance and difficulty of the trail is prohibitive and so the site is not listed in any of the guide books. I am the only person he has guided here.

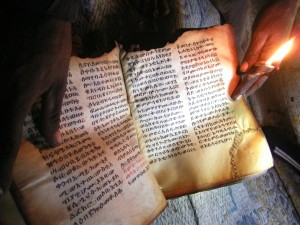

Once inside, joined by the guard and another local man, the priest commences the usual pattern of bringing out, one by one, a series of outstanding relics and manuscripts. Some, I am told, date to the 6th century. The five of us sit for a magical hour on the floor, pouring over vellum manuscripts, some bound in olive wood, others unbound and stored in leather pouches. The priest reads to us in rhythmic Ge’ez. I observe that a torn page has actually been sewn back together and we all laugh examining the careful repair that is centuries old. There is an early example of what appears to be an index. Destow and I remark upon early patterns of punctuation, space between words, and so on.

It seems the history of technologies for writing and literacy development is somehow encapsulated in this beautiful, ancient nation. Papyrus grows thick on the shores of Lake Tana. In the churches and monasteries incunabula and other early examples of the book on vellum are still consulted and used in services. Scribes write with bamboo styli on scrolls of vellum outside the the churches of Lalibela. Books of every type are in demand–rare and expensive. The cost of publication is high. Perhaps here we have an example of what Graff (e.g., The Labyrinths of Literacy) would call a “newly literate” population. And yet, mass literacy remains a goal, not a reality. The “education for all” initiative (free education to grade three) is, after all, in its infancy (see, for example, this article).

We take an alternate route back through a narrow valley that is home to many villages. Here I see four rural schools: two for aspiring priests and two public. Destow tells me that aspiring priests, all male, start at six or seven and are schooled in Ge’ez, the formalities of the Ethiopian Christian Orthodox service, and the scriptures. They are not exposed to curriculum beyond this and so are leaders in the community with a very focused perspective. Today they are learning outside–chanting in clearings near the path. Of the public schools I see, one is a makeshift shelter with no walls roofed with a tarp. The other has walls of tarp and one or two additional buildings of mud and straw. None of these schools have power or running water because such amenities, if they are available at all, are not found beyond the immediate town site. Lalibela has no serviced suburbs, and its mostly unpaved roads are primarily populated with donkeys, mules, and pedestrians.

I will write of our visit to the Lalibela school in the next post.