2.1 Tar Heel State

Mum always said that I’d be able to find my way home. I don’t really know what convinced her of such a thing, maybe it was simply a mother’s intuition, or maybe just shallow words used to convince herself that I would somehow make it back in one piece. Probably a bit of both. Of course, as mothers always are, she was right.

The farm looked exactly the same as the day I had left. “Tobacco isn’t as big of a crop as it used to be when I was your age” my Pa would say as he peered over the golden leaves on our spacious white porch. Even so, the year round harvest still continued, they still called us the Tar Heel state, and even though it was some tough work, Pa always managed to do the harvest right and we would always have food on the table.

When I was in school, the teachers always said that the tobacco won’t last, and that we’ll all either have to find factory jobs or join the army and fight the good fight. My buddies and I always thought a union job wouldn’t be too bad – nine to five, decent pay, lunch packed by the wife, and the Malboro factory was just down the road from the old farm. Sounded pretty alright.

But that was all before the war.

Now, it wasn’t like in the movies where suddenly all the boys were shipped off in a day over the star spangled banners, waving good bye to all the pretty ladies at the dock. No, not like that at all. It happened very slowly, which was probably much worse.

I ended up did getting that factory job first. But it sure wasn’t pumping out cigarettes from a machine. Our little town was told by the Department of Wartime Resources to make bombs, so we did. Even Pa had to give up the farm to join us in the factory. Even compared to the really bad harvest years, I’ve never seen him so down. Like the life was just drained from him.

Mum was scared of course. Any day an officer could drop off the letter that took her son away. About four months in, the officer in his perfectly pressed uniform came, said hello, and dropped off the letter. I was on the truck by Monday, and Mum took my spot in the factory by Tuesday.

War was hell on the fontlines, but I managed to endure. One month, two months, three months, six months, two years.

Then one day, I was called into an officer’s bunker. He told me, in his perfectly pressed uniform, that the munitions plant in our little town had an accident. The town was now nothing more than a hole in the ground.

Because of this “indescribable tragedy”, I was “honourably discharged from active service and to be returned home immediately.”

Heh, home.

When the truck dropped me off at the farm, I was surprised to find that it was completely untouched by the blast. The plates from breakfast that Mum and Pa had before they left for work that day were still in the sink.

Everything about the farm still looked like home and smelled like home. But I was alone.

—–

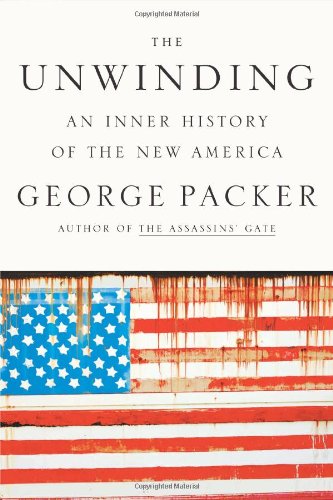

I had recently started reading The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America by George Parker, a collection of short stories that tie together to overall narrative of an unwinding America. While I’m only a couple stories in, the one that struck me most was about a man who grew up on a tobacco farm and his struggles with family and finding a sense of home. That story served as an inspiration for the initial concept of my own story.

I had recently started reading The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America by George Parker, a collection of short stories that tie together to overall narrative of an unwinding America. While I’m only a couple stories in, the one that struck me most was about a man who grew up on a tobacco farm and his struggles with family and finding a sense of home. That story served as an inspiration for the initial concept of my own story.

Parker, George, The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America, New York, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013

Bran Ham Photography, Barns of the American Midwest – Tobacco Farm, accessed January 30th 2014, web gallery. <http://www.branhamphoto.com/barns-of-america/>

Wow – what a photo to begin with – this image is as powerful as your story, nice choice 🙂 You have written quite a powerful short story of home — or, rather, homelessness. Actually your story contains a sharp contradiction, doesn’t it? Like the kind of contradiction Chamberlain describes. One moment we are reading our way into a family of honest characters, and the next moment: poof — we are all alone. The house still stands, the breakfast plates waiting to be washed …. by the lone survivor. Tragic. Thank you.