Assignment 3:7 Close Reading Green Grass Running Water

During an inaugural reading of Green Grass Running Water it is nearly impossible for even the most well-read scholar, history buff, or pop culture aficionado to unfold every individual layer of reference Thomas King has intricately layered into the novel. Using Jane Flicks Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water, I will attempt to unpack all of the references King makes between pages 23-37. I chose this portion of the book as it is, in most cases, the first time the reader is introduced to these characters and there for the nuances and references that lay the groundwork for much of the novel’s central themes including water, colonialism, and Indigenization.

Babo speaks with Sargent Cereno (p. 23-28)

The story break opens with our first introduction to Babo Jones, who Flick identifies as a reference from ‘[Herman] Melville‘s story “Benito Cereño” in Piazza Tales (1856),’ (Flick, 145). Flick further explains that “Babo is the black slave who is the barber and the leader of the slave revolt on board the San Dominick” (145). King has gender swapped the character of Babo Jones and plays on this swap using a comedic exchange where Sargent Cereno continues to confuse “Ms” and “Miss” while Babo continually corrects him saying both “I am not married” (King, 23) and “some people think Babo is a man’s name” (24).

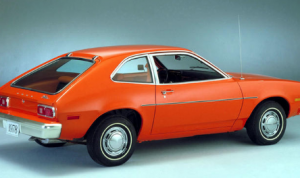

King further correlates the Babo of his story and the Babo of Melville’s story by lacing in a multitude of references to ships. King describes Babo as looking out the windows at the hospital to see her car, a Ford Pinto, that King uses as a double entendre as he likens the state of the car to a ship, specifically that of Columbus’s ship, the Pinta” (Flick, 146). Babo sees the car “sitting in a puddle of water” (24) and that “the Pinto looked a little like a ship” (27) and eventually Babo witnesses the puddle slowly rising and the car floats away (28). The second part of the entendre is the term “Pinto” as both the make of the car, but also in reference to “plains horse[s]…Jokes about naming cars after horses, Indians and explorers may be at work here” (Flick, 146).

Babo is sitting and being recorded by police Sergeant Benito (Ben) Cereño whom Flick describes “is a character in Melville’s story ‘Benito Cereño’” A mutiny occurs on board ship, led by the black barber and slave leader, Babo,” (145). This passage is rife with a power play between Babo and Cereño where Babo controls the conversation by injecting little quips and distractions by evading Cereño’s authority. Babo asks Sergeant Cereño “Is that [name] Italian or Spanish, or what?” (25); “What’s your first name? Let me guess. Is it Ben? That’s my boy’s name” (26), and lastly, Flick explains that, “King provides lots of little jokes that reinforce the connection between Babo and a ship. For example, she carries around Life Saver candies (25)” (145).

Here a lot of characters are introduced by name but are absent, with the exception of officer Jimmy who stands by the door. Flick surmises “a possible connection with Captain Delano of “Benito Cereño,” but more likely Columbus Delano, a career politician who was head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the administration of Ulysses S. Grant,” (146) reinforcing an ongoing cultural narrative that police are not the friends of Indigenous people, but instead political and governmental pawns.

The Lone Ranger, Ishmael, Robinson Crusoe, and Hawkeye (p. 29)

This is going to sound like bad joke but…what do the Lone Ranger, Ishmael, Robinson Crusoe, and Hawkeye all have in common? They all have a stereotypical “Indian” sidekick. In King’s rendition these characters are reimagined as Indigenous elders, escaping from a mental institution, or more poetically, the institutionalization of their Cowboy/Indian stereotypes. Their journey is one of healing and returning to the land and tradition. In this very short passage these travelling characters stand in a field and survey the land in front of them, they note both that “here they are” as well as “are we lost again” drawing a parallel between the relationship of the journey they are on (and taking us on) and the destination as well. They take in the land, sun, grass, and wind as well as walk in circle. All these elements in addition to the characters being able to “see the edges of the world in all directions” are reminiscent of the Medicine Wheel. It is described that “the Medicine Wheel teachings are based on a circular pattern and cyclical set of four: the four Seasons, the four stages of Life, the four Bio-psychosocial and spiritual aspect of a person,” (Laframboise & Sherbina). The following are Flicks observations of each character:

LONE RANGER Masked man with faithful Indian companion, TONTO. Hero of western books, the 1933 radio serial written by Fran Striker (see Yoggy 221), the 50’s television series, and numerous movies, among them…He is a Do Gooder. The Texas Rangers myth has it that one ranger could be sent to clean up a town. Tom King’s interest in the Lone Ranger also extends to his work as a photographer. He is engaged in a project, Shooting The Lone Ranger, to capture well known Native Americans wearing the Lone Ranger mask. (141)

ISHMAEL Character in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, who begins the story with one of the most famous opening lines in American fiction: “Call me Ishmael.” He is strong friends with the cannibal QUEEQUEG, and when Moby Dick destroys the Pequod, Ishmael survives by staying afloat on Queequeg’s coffin. The name is Biblical: Gen.15.-15 (143).

CRUSOE, Robinson Hero of Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe (1719). This narrative of a shipwrecked mariner, based on the true story of Alexander Selkirk…He is aided by his Man Friday, the “savage” he rescues from cannibals, and then Christianizes. The novel contains meticulous details about survival. King mocks Crusoe’s passion for making lists and for weighing the pros and cons of various situations: “I was very pensive upon the subject of my present condition when reason as it were expostulated with me t’other way…” (Defoe 62). (142).

HAWKEYE Another adopted “Indian” name. Most famous of the frontier heroes in American literature, when the frontier was in the East— Appalachia, before the frontier “moved” West. Hawkeye is one of the nicknames for James Fenimore Cooper’s Nathaniel Bumppo, a white Canadian Literature 161/1621 Summer I Autumn 1999 Reading Notes woodsman and guide with knowledge of “Indian ways.” …He has a faithful Indian companion, CHINGACHGOOK. (141-2).

Lionel Makes a Big Mistake (p. 30-37)

This next short passage presents as a whimsical story of a young boy trying to take advantage of the perks of having his tonsils removed and ending up on an unconventional journey. However the themes of being separated from his family, the threat of a heart operation, and the systematic discretization of Indigenous medicines heavily parallels with the very real Canadian history of residential schools and stolen children. The chapter opens with young Lionel jealous of schoolmate who missed class to have her tonsils out. First, Lionel’s mother brings him to see Martha Old Crow, “a medicine woman, the “doctor of choice” for people on the Reserve, (146). Where the story begins with band doctors and family close by and bits of whimsy like the “frog doctor” (King, 31), it gradually builds up large hospital institutions and separation from family and a sense of terror (35).

As the sense of anxiety and unease grow characters of stereotypical masculine strength are introduced as ideals for Lionel. His cousin Charlie taunts him by asking “what would John Wayne do” (33)? Flick explains that, “Lionel’s childhood desire to be John Wayne…signals his denial of ‘Indianness’” (Flick, 147). A curious exchange leads to the recommendation of George Morningstar, who is described as a “real smart choice, that one” (King, 33). Flick explains that “his name alludes to Custer. “Son of the Morning Star” or “Child of the Stars” was the name given to George Armstrong Custer by the Arikaras in Dakota territory. (Flick, 146). Custer was a Union General in the Civil War and famous Indian fighter who has acquired mythic status in American history (149). King uses Wayne’s movie costume of leather jacket, hat and gloves to parallel George Morningstar’s “Custer” jacket, hat and gloves (147).”

Norma makes a thinly veiled reference to the Kennedy administration stating “Camelot’s progressive, you know. Indian Doctors weren’t good enough” (King, 33). Which Flick explains that, “the Kennedy administration was identified with this idealistic, roundtable approach to government. Camelot also applied to the administration’s covert security operations (Flick, 151).” I believe this implied that while the Kennedy administration appeared to be in support of the Indigenous population they lacked in follow through.

Norma tells Lionel he reminds her of his Uncle Eli, (36) more formally referred to as Eli Stands Alone. Flick explains, “the name suggests Elijah Harper, who blocked the Meech Lake Constitutional Accord in 1990 by being the standout vote in the Manitoba legislature. He voted against a debate that did not allow full consultation with the First Nations and that recognized only the English and the French as founding nations. King may also have drawn upon the name of Blood Elder, Pete Standing Alone, subject of a National Film Board documentary in 1982 (150).”

The chapter concludes with the narrator cataloguing the instances where Lionel’s misreported heart surgery negatively affects his attempts to lead a normal life. He is turned down for a car loan and a part-time job, harkening to the negative lasting impacts residential school had on its survivors in that they were viewed to only have a grade six education, and therefor not deemed suitable for work or reliable enough for loans. An ongoing racist mar on Canadian History.

Works Cited:

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, by Daniel Defoe, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/521/521-h/521-h.htm

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Moby Dick; or The Whale, by Herman Melville,

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2701/2701-h/2701-h.htm

Flick Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 140-162 (1999). Web. 4 April 2013.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

Laframboise, Sandra, and Karen Sherbina. “Links.” THE MEDICINE WHEEL – Dancing to Eagle Spirit Society, 2008, www.dancingtoeaglespiritsociety.org/medwheel.php.