In Memory of Chris Meade, and For Downing College Archive, Cambridge.

In a study that is concerned with family networks such as Writing the Empire: The McIlwraiths, 1853-1948 (UTP, 2021), it is always a fascinating moment when – intentionally or not – they become enmeshed in another nexus or even several of them at once. During officer training at Cambridge and as a member of the British Army of Occupation in Germany, young T.F. (“Tom”) McIlwraith formed close relationships with his army friends that he found difficult to leave behind when he was demobilized, but he was also drawn into the academic family both in the literal and the figurative sense well before he began his studies with W.H.R. Rivers, A.C. Haddon and William Ridgeway at Cambridge. His initial guide was A.C. Seward, Master of Downing College from 1915 to 1936, who recommended that he study anthropology and introduced him to his colleagues. Equally important for T.F.’s welfare was Seward’s wife Marion, a relationship strengthened by Tom’s friendship with scientist Michael Sampson, fellow student at St. John’s College and future husband of the Sewards’ daughter Phyllis. In numerous ways, the support McIlwraith enjoyed from his Cambridge mentors extends the findings of scholars like Tomás Irish and Heike Jöns who have investigated the significance of the academic family for teachers and students alike.

McIlwraith’s initial contact with the Sewards was not promising. He and his fellow soldiers sniggered at the “the funny old boy” who joined them in April 1918 to observe drill and, apparently not knowing any better, replaced the proper military salute with a careful bow. McIlwraith acknowledged that this decorous gentleman was “a grey-haired and venerable old don” and indeed Master of Downing College, but it took a month until he had learnt to comment more respectfully on him. The young soldiers were dismissive when the Master objected to them climbing through windows at Downing College, but they mended their ways when the Sewards began a tradition of inviting soldiers from Peterhouse College, especially overseas soldiers, to their home for conversation and entertainment, even if the food they served never seemed to be enough for their bottomless appetites. T.F.’s first encounter with Marion Seward was similarly inauspicious: for Empire Day at the Tipperary Club, a fellow soldier volunteered Tom’s services for a recitation of Kipling’s “The English Flag,” and he crumpled up the note bowing out of the occasion only because, faced with Marion Seward’s note of grateful thanks, he suddenly remembered his manners.

Researching the Sewards and their role in WWI Cambridge was a daunting exercise. Its eventual success proved the significance of the internet but also of the humble clippings file in establishing the necessary connections. The nature of the “giddy club,” as he called it, at which Tom McIlwraith recited Kipling’s poem remained elusive until Jenny Ulph, College Archivist of Downing College, forwarded a clipping identifying it as the Tipperary Club, one of several such organizations in WWI Britain. A search through contemporary Cambridge newspapers clarified its wide-ranging social and educational activities on behalf of military families, partly inspired by similar initiatives during the Anglo-Boer War, and the royal and military patronage it enjoyed. Indeed, Marion Seward’s efforts on behalf of the Club were so strenuous that they were blamed for her early death from heart disease shortly after the war. Cambridge University Press printed a commemorative booklet – a rare item found by accident among AbeBooks offerings – in which her husband eulogizes her as one whose “religion was service,” and which describes the Club’s working-class women as forming her honour guard at the funeral.

Marion Seward had another identity: she was a painter. She was associated with a community of landscape artists at Walberswick where the Sewards owned a cottage, and as a skilled botanical artist, she illustrated her husband’s books. When this became impossible because of other commitments during the war, her daughter Phyllis, trained at the Slade School of Fine Art, filled in for her when he published Fossil Plants: A Text-Book for Students of Botany and Geology (1917). T.F. McIlwraith benefitted from Seward’s work as an artist too when she presented him with two sketches of Cambridge as a keepsake before he was deployed to the front. He immediately sent these home to Canada for safekeeping where they rested, unidentified, among the family papers until the gradual emergence of the Sewards’ story allowed his son to recognize them for what they were.

An important document that brought the two strands of Marion Seward’s work together was a journal with water colour sketches describing the couple’s trip to the BAAS Congress in Australia in 1914. Along with the best of British and European scientists also on board the Euripides, they were informed of the outbreak of WWI by “marconigram” while they were at sea. Her description of visiting with dozens of her husbands’ pupils, now in professorial and administrative positions throughout the British Empire, not to mention the sudden challenges of running a conference under wartime conditions and returning home as the enemy began to torpedo ships, provides an extraordinary female counterpart to the archaeologist Henry Balfour’s journal of the same occasion. Even in the early days of the war, both Sewards’ commitment to service as their religion was apparent. Found circuitously through an obituary of one of her descendants, Seward’s diary remains in the possession of the family, and it is a treasure.

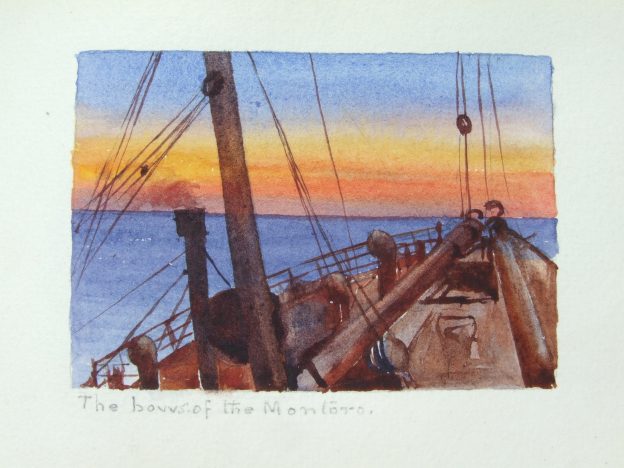

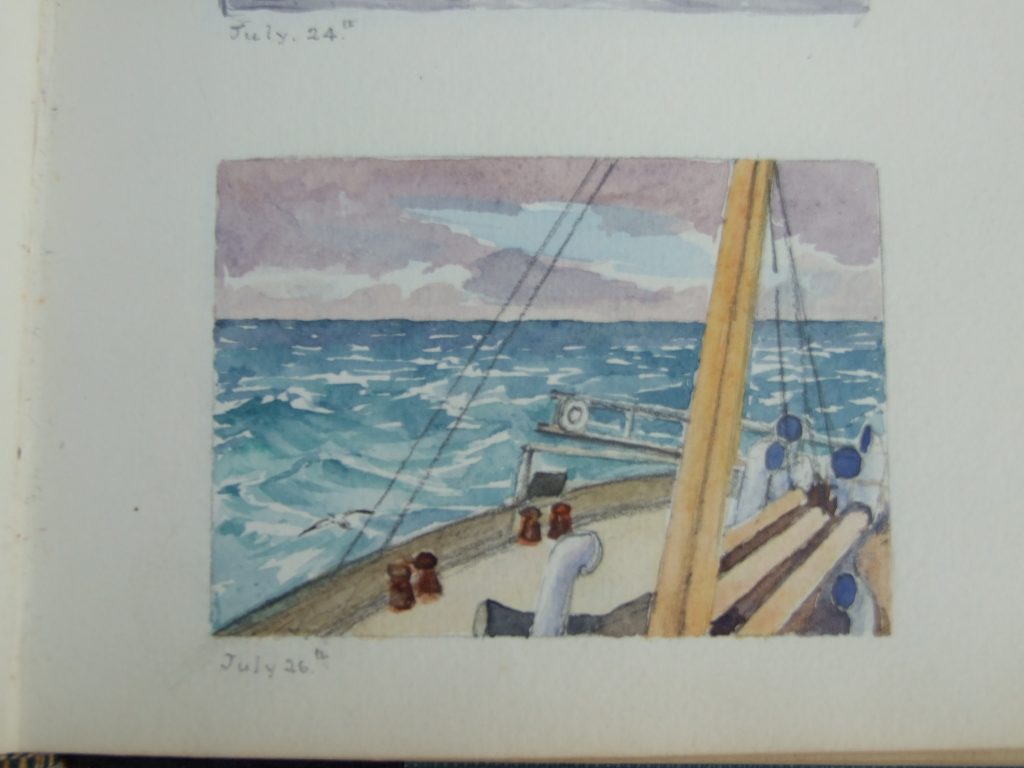

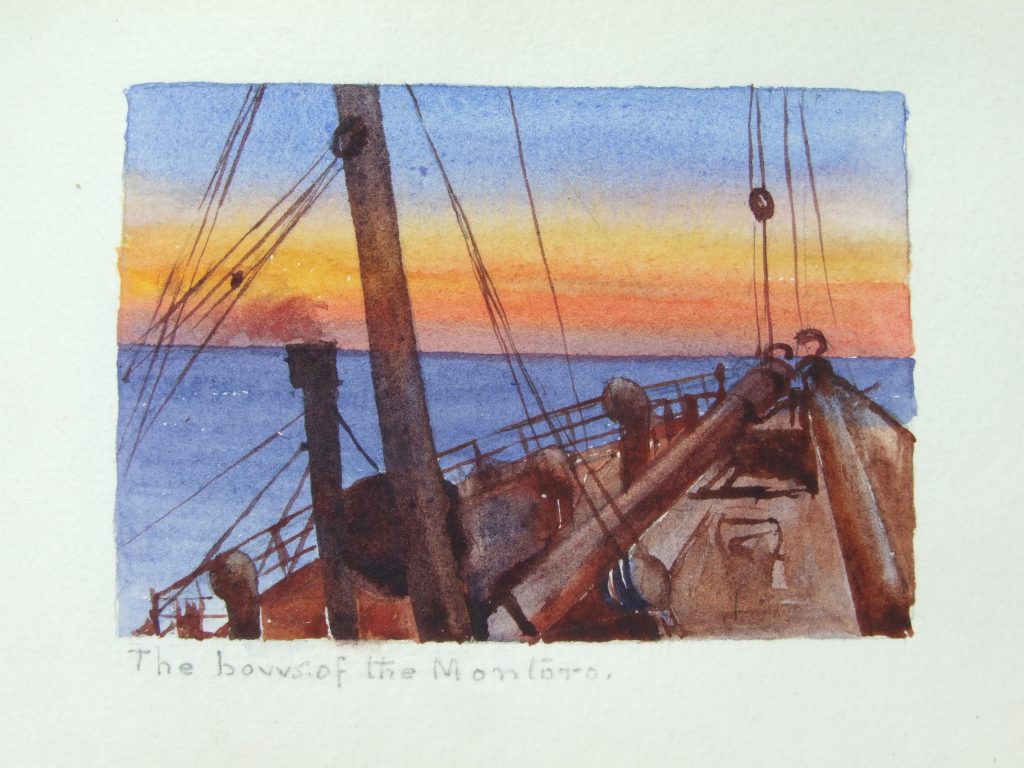

Here are two of Marion Seward’s watercolours from the 1914 trip to Australia:, along with the matching entries in her journal:

Sunday, 12 July 1914

The night was quite comfortably cool. P [Phyllis, the Sewards’ daughter] and I took our cameras to the muster and tried to get snaps of the Captain as he inspected the men. Went to service [;] some of the passengers had practiced the canticles so that we sang them which made the service brighter. I asked the Captain if he would be shocked if I sketched on a Sunday (one never knows how easily a Scotchman may be shocked) but he said ‘please thyself and it can’t hurt me.’ However, after trying hard for a quarter of an hour, had to give it up as my board was nearly blown into the sea and it was impossible to steady a brush in the wind. Rested and did one small sketch in my book until tea.

Thursday, 17 September 1914

[After war had been declared, sketching and photographing was curtailed, and the Montoro observed blackout after sundown].

After a rest had quite a busy afternoon doing odds and ends of mending etc. and after tea, Dr Lander, Dr Sidgwick and I had a game of tennis which was warm work. Then more sketching until it was time to watch the sunset, colour was gorgeous, brilliant red with purple clouds. Every place was shut up again at sundown and it was very close. We sat on the deck in the dark as before, but were a little more lively as Dr Lander told some [S]cotch stories and B. [Bertie? A.C. Seward] told others, had a nice talk to Prof. Forbes when having some refreshment before going to bed […]

Acknowledgements: With thanks to Clare Meade for permission to reproduce two water colours from Marion Seward’s diary.