Convention on Biological Diversity

The Convention of Biological Diversity is the most comprehensive international biodiversity protection regime (Markussen, Buse, & Garrelts, 2005). It was signed at the Earth Summit in Rio in 1992, and implemented at the end of 1993. The convention has many focal areas, outlined in the list below, each with goals, sub-targets and indicators, that demonstrate the mitigations of pressures on biodiversity and the reduction of negative impacts such as losses of ecosystem services.

Reducing the rate of loss of the components of biodiversity, including: (i) biomes, habitats and ecosystems; (ii) species and populations; and (iii) genetic diversity;

Promoting sustainable use of biodiversity;

Addressing the major threats to biodiversity, including those arising from invasive alien species, climate change, pollution, and habitat change;

Maintaining ecosystem integrity, and the provision of goods and services provided by biodiversity in ecosystems, in support of human well-being;

Protecting traditional knowledge, innovations and practices;

Ensuring the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the use of genetic resources; and

Mobilizing financial and technical resources, especially for developing countries, in particular least developed countries and small island developing States among them, and countries with economies in transition, for implementing the Convention and the Strategic Plan.

List: Focal areas of the CBD text (UNEP, 2015)

In the convention text, there were many targets set for 2010. Although none of the 21 targets were achieved worldwide, there was local and regional progress for goals such as reducing the impact of pollution or conservation at certain scales (Alkemade, et al., 2009).

Endangered species legislation

CITES, 1975

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora is an international agreement, aiming to ensure that international trade of species does not threaten their survival. CITES targets the pressure of overexploitation, currently protecting over 35,000 species of animals and plants (CITES Secretariat, 2013).

National legislation examples

Around 170 countries have national biodiversity strategies and action plans (Alkemade, et al., 2009).

ESA, 1973

In the United States’ Endangered Species Act, listed species cannot be killed, harmed or traded, their critical habitat must not be damaged or destroyed, and there is an obligation to prepare recovery strategies. (Waples, Nammack, Chocrane, & Hutchings, 2013). It therefore reduces pressures such as habitat loss and overexploitation of specific species

SARA, 2002

Canada’s species-at-risk legislation, the Species At Risk Act, was enacted to prevent wild species from becoming extirpated or extinct. Assessment is done by COSWEIC, and the government chooses to list, refer back, or not list suggestions based on socioeconomic factors. The effects of listing are similar to those of ESA but recovery strategies must be prepared within a set amount of time (Waples, Nammack, Chocrane, & Hutchings, 2013).

Endangered Species Assessment Lists

IUCN Red List

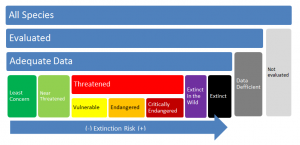

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature Red List, assesses the status of species (as in the figure below) to inform decisions and priorities for conservation action.

Figure : Structure of the categories of the IUCN Red List (after IUCN Species Survival Commission, 2012)

Protected areas

Across the world, different levels of government along with NGOs and other groups have responded to biodiversity loss by creating protected areas as an attempt to mitigate the pressure of habitat change. Connected, large reserves buffered from areas of intense human use are effective at sustaining biodiversity (Cain, Bowman, & Hacker, 2014, p. 559). Challenges in implementing protected areas such include human rights of native groups and pressures from industry. Many studies are being done on whether sustainable use conservation areas[2] can be effective in preserving biodiversity (Almudi & Kalikoski, 2010).

Furthermore, work is being done towards ecological restoration or ‘rewilding’ of lands, including an expected 200,000 square kilometers of land in Europe by 2050 (Alkemade, et al., 2009).

Market tools

One example of a market tool is payments for ecosystem services, which are voluntary mechanisms creating positive incentives for limiting activities that cause environmental degradation.

REDD+

Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation is a UN program which incentivizes developing countries to keep forest stands by offering payments for actions done to reduce or remove forest carbon emissions. This targets the pressures of both climate change and habitat loss.

*Although responses can relate to any of the four other DPSIR categories, most of these responses relate to the pressures on terrestrial biodiversity.*