Mid-century: leaping into urbanization

Massive changes in the world of work and commerce, the American population, transportation technology, and the social organization of the cities started really getting under way as the nineteenth century began to roll into its middle decades. The two most significant factors in this change were both imports from Britain and continental Europe: industrialization, and the waves of immigrant labourers expanding the American work force. Private enterprise still ruled, and much development was improvised, but urban expansion on all fronts began to force city governments to extend their areas of responsibility. The nineteenth-century city was gradually organizing itself.

By 1815, England’s industrial revolution was in full swing. The newly-invented steam engine, new steam-powered machines for making cloth, and new coal-burning furnaces for making finished metal out of iron ore, had all allowed a new economy to be geared around factory production. This meant a transformation in the workforce too, with a culture of apprenticing and trade-mastery being replaced by one of wage labour and shift-work. Factories began to open in American cities as early as 1814, but it was not until the 1860s that the English industrial revolution’s technologies and social changes had fully established themselves in the U. S. (Chandler). Gas- and oil-lamps became more plentiful on the largest city streets in the early morning and evenings, allowing the length of the working day to be set to a year-round standard.

As a factory economy developed, immigrants were pouring into America looking for work. America’s reputation for “democratic ideals and work opportunity” (Byrne) may have been inflated, but it was attractive: nearly a million Irish people fled the potato famine to U. S. port cities during the 1840s and 50s. They came willing to invest energy in the local economies and in building a home for themselves in America; they were met with opportunity, but also with a strong anti-Catholic sentiment from the Protestant majority. Uneasiness about the “Catholic hordes” was not helped by the fact that the Irish arrived in such huge numbers as to form substantial, if poorly-housed and struggling, populations in each city. Other major waves of immigration flowed into America throughout the rest of the nineteenth century; a large influx of Germans arrived alongside the Irish in the 1850s, meaning that by 1860 nearly half of New York City’s expanding population was Irish- or German-born.

A specialized street-scape

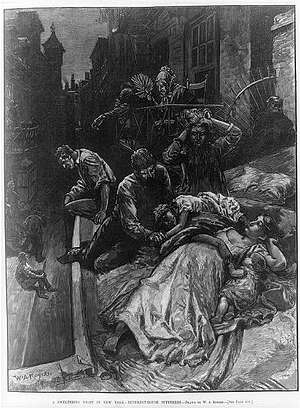

|

|

| “Sweltering Night in New York – Tenement House Sufferers” |

During the middle decades of the nineteenth century, factory-work and the large economies necessary to support mass-production gradually widened income gaps between rich business owners and poor wage labourers. A middle-class of managers and shop owners catering to the wealthy population was also expanding. The “walking cities” of the early nineteenth-century began to re-organize themselves in response to this changing class structure. The actual ground-territory covered by each city was at this point only very slowly expanding: transportation technology was developing, but not yet quickly enough to allow cities to sprawl. The city populations were booming, however, and population densities soared. Overcrowding placed extra stress on sewage-disposal systems, encouraged the spread of disease, and meant that immigrants with little ready cash, as well as the U.S.-born working classes, were forced to pay too much for even the least hospitable residences. Tenement houses – apartment buildings where lower-class families were jammed into tiny spaces with many windowless rooms, having to share sinks and basement privies – began to appear in American cities (Hayden).

The pressures of overcrowding and the newly stratified class structure resulted in the earlier decades’ mixed-use city streets being replaced by a more specialized urban geography. Residential neighbourhoods cropped up, differentiated by class and ethnic background. The spheres of business and home began to belong in different areas of the city, an arrangement which “better sustained a developing interest in domesticity” (Bender). Slums developed near the wharves and factories, and at the outskirts of the cities. And the idea of a “downtown” – a distinct commercial district for shopping and entertainment – began to become a reality (Bender).

The American night-life comes of age

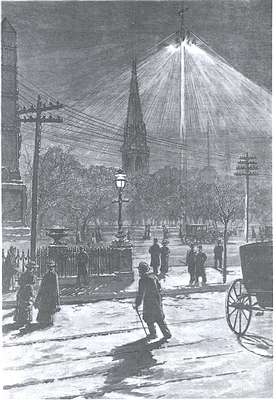

|

|

| Electric Arc Lights in New York City’s Madison Square, 1881 |

Gas lighting was becoming cheaper and more efficient during these middle decades, and was slowly replacing oil lamps on the major city streets. Gas lamps burned up to ten times more brightly than oil ones. Competition among shop-keepers in growing commercial centers and theatre districts of the biggest cities began to ensure that storefronts along the big boulevards would remain brightly lit with gas well into the nighttime. When Philadelphia’s New Theatre became in 1816 the first American building to be fully lit by gas lighting, theatre entertainment itself was transformed: instead of requiring actors to step into pools of oil-lamp light to deliver their soliloquies, or to gesture wildly to be visible in the shadows, the gas-lighting allowed subtlety on stage (Jakle 31-2). Meanwhile, the wharves and poorer neighbourhoods remained sparsely lit with dimmer oil lamps. “At night,” writes one historian, “these areas stood in stark contrast to the best gas-lit portions of the city” (Jakle 31).

If the majority of city streets remained dark and potentially dangerous at night, the idea of a public nightlife nevertheless took hold of the city populations. As well as the theatres and the fashionable salons and dining rooms in big hotels – which had existed in the earlier decades too – businessmen opened night-time entertainments which not only depended upon, but celebrated, the new night lighting (Jakle): pleasure gardens, coffee houses, music halls, museums, and department stores stayed open into the night. Wealthy women were newly able to shop and socialize on the evening streets.

The construction of natural gas mains under the busy streets was too costly and required too much infrastructure to be carried out independently by each of numerous private agencies. City governments began to supervise these services, granting a single gas company the right to construct mains and supply gas in any particular area of the city (Jakle 30).

Police and the New City Government

During the 1840s and ’50s, city governments began to expand its responsibilities in ways that demanded more than simply handing out franchise rights to transportation and gas companies. They began to raise taxes, and used this money as well as borrowed funds to begin building public water-works and sewers. In fact, by the end of the century, the larger cities would boast the “most extensive water and sewer systems in the world, guaranteeing middle-class Americans the comfort and convenience of the indoor flush toilet and bathtub” (Teaford).

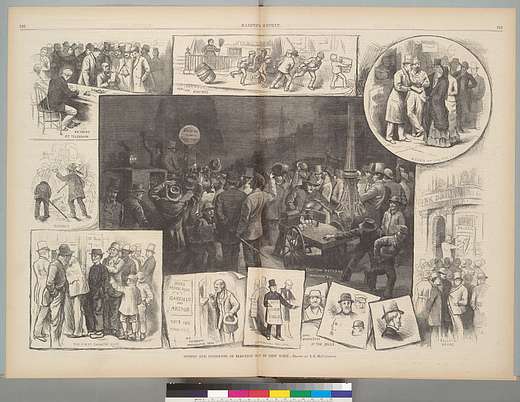

During these decades as well, the cities created professional police forces. Unlike their British counterparts, these policemen were exclusively the employees of the city governments; they saw themselves “as administering justice on the street,” as opposed to representing the state justice system (Monkkonen). They wore uniforms designed both to make them a visible warning to potential criminals, and to prevent them from drinking or gambling themselves. Regular salaries disposed them to be helpful to the poor, and their tasks expanded spontaneously from simple crime-prevention to helping the average citizen find his or her way, directing traffic, and even boarding homeless people overnight at the station. When women were hired into the forces as “matrons” near the close of the century, their responsibilities included taking care of lost children, homeless women and women prisoners. Black men were hired as early as 1814 in New Orleans, but rarely otherwise until the close of the century; in these cases, they were hired specifically to patrol black neighbourhoods.

Elected city governments often used their power to hire people from their own social groups, which meant that “the ethnic and racial composition of the police force became a mirror of local politics” (Monkkonen). This lead in turn to resentment on the part of well-to-do WASP minorities in certain cities, who disliked immigrants’ access to city jobs. The rising taxes also lead to charges of corruption in the city governments. Meanwhile, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the influential “bosses” of large semi-official social networks (dubbed “machines”) were rumoured to draw financial tributes from their contacts and dependents. In turn, these bosses in turn arranged not only jobs and smaller favours – turkeys on poorer dinner tables at Christmastime – for their contacts, but also shouldered the financial burden of large-scale urban improvements, including street lighting and road-surface maintenance (Stave). These two sorts of “government” may well have involved corruption, but also shaped more tightly organized and higher-quality cities (Monkkonen, Stave).

![]()

|

| “Scenes and Incidents of Election Day in New York” ca. 1880 |

Private Eyes

The new police forces in their blue uniforms were not perfect crime-fighting machines. Their loyalty to the city governments who paid their salaries meant that they sometimes walked party lines: until the late nineteenth century this meant that the police would “support strikers, say, or […] refuse to implement morality legislation like Sunday closing laws” (Monkkonen). And they were not yet properly trained. New York City’s Draft Riot of 1863 was violent and vicious; mobs of the city’s white population attacked black citizens, lit fires, and lynched people. The police forces of the day were “unable to coordinate their maneuvers and lacked the training and discipline” necessary for handling such large bands of violent people (Monkkonen). At the best of times, their presence on the city streets simply prevented some crime and allowed them to tackle illegal activities when they found these in progress.

As a partial solution, the city police forces began hiring detectives by the late 1860s. These men worked in street clothing, which enabled them to track criminals or uncover drug, gambling, and prostitution rings when they could find or extort evidence. (It also made them difficult to supervise.) Like the powers of the rest of the city police department, theirs were bound within city limits. Especially when railroad travel took off late in the century, their boundaries made tracking certain crimes very difficult. Wealthy citizens with a crime solved this problem by hiring a new sort of nineteenth-century entrepreneur: the private detective. Like their civic servant counterparts, the private detectives tended to work through deception and borderline-illegal activity, attempting to insinuate themselves into the trust of people directly connected to the crimes. (See Monkkonen for an introduction to the ways the American detective profession began to make its way into popular fiction.) (SB)

Works Cited

Bender, Thomas. “The Reader’s Companion to American History – Urbanization.” Houghton Mifflin College Division. http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_088600_urbanization.htm.

Byrne, Julie. “Roman Catholics and Immigration in Nineteenth-Century America.” Nov 2000. Nov 14, 2005. www.nhc.rtp.nc.us:8080/tserve/nineteen/nkeyinfo/nromcaht.htm.

Chandler, Alfred D. “The Reader’s Companion to American History – Industrial Revolution.” Houghton Mifflin College Division. http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_045300_industrialre.htm.

Hayden, Dolores. “The Reader’s Companion to American History – Housing.” Houghton Mifflin College Division. http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_043300_housing.htm.

Jakle, John A. Illuminating the American Night. Baltimore: John Hopkins UP, 2001.

Monkkonen, Eric H. “The Reader’s Companion to American History – Police Forces.” Houghton Mifflin College Division. http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_069700_policeforces.htm.

Stave, Bruce M. “The Reader’s Companion to American History – Urban Bosses and Machine Politics.” Houghton Mifflin College Division. http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_088500_urbanbossesa.htm>.

Teaford, Jon C. “The Reader’s Companion to American History — City Government.” Houghton Mifflin College Division. http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_016800_citygovernmen.htm>.

Works Consulted

McSwain, James B. Review of Sara E. Wermiel’s The Fireproof Building: Technology and Public Safety in the 19th-Century American City. Nov 2000. Nov 14, 2005. www.eh.net/bookreviews/library/0313.shtml.

Morrison, Donald. “Making Cities Work: How Engineers Transformed Late 19th-Century American Urban Centres.” www.eng.nsf.edu/mr/ret_2002/making_cities_work.pdf.

Osborn, Tracy. “Teacher’s OZ Kingdom of History – 19th-Century America.” July 11, 2005. Nov 14, 2005. <www.teacheroz.com>.