The early 1800s

The early 1800s: private enterprise and the “walking city”

During the first decades of the nineteenth century, American cities were still small in size and, by today’s standards, distinctly un-organized. Only five cities had more than ten thousand inhabitants (New York City, Philadelphia, Boston, Charleston, and Baltimore). These cities were all centered around their harbours, since commercial trade depended almost entirely on boat traffic. As in the previous century, city governments were principally interested in promoting commerce – they fixed prices and supervised the wharves and marketplaces (Teaford). But they had little else to do with urban planning, or with providing public services and utilities. Citizens took these matters into their own hands. Entrepreneurs saw the general need for basic services as a business opportunity, and for decades everything from nighttime safety to water supply was available only for those who could afford it.

Dark nights

Henry Thoreau: “Men are generally still a little afraid of the dark, tho’ the witches are all hung, and Christianity and candles have been introduced.”

|

|

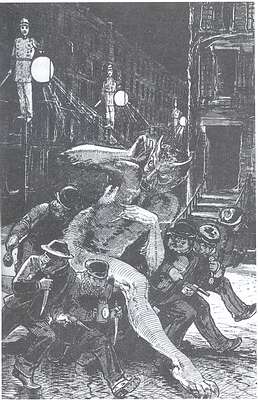

| “The Powers of Evil are Fleeing Before the Light of Civilization” |

City streets were dark enough in the early nineteenth century that walking at night was a fearful activity, particularly for women. Americans imagined criminals and the lure of vice lurking in the shadows, and evenings were generally spent indoors. A Boston newspaper argued in 1772 that public lamps posted along the sidewalks would protect “those who ventured forth at night on calls of business or friendship from ‘insult, abuse, and robbery'” (qtd. in Jakle 23), and Boston streets began to be lit with candle lamps the following year. Other major cities followed suit, and New York City required that a lamp be posted in front of every seventh house. But these streetlights — in which candles were replaced with brighter oil lamps by the late 1700s — were to be paid for directly by the people living around them, a fact that prevented the lighting of streets in poorer neighbourhoods. Moreover, they were set far apart; pools of light fell at distant intervals along the sidewalks, and the contours of the streeets were hardly visible (Jakle 20). Cheaper oil mixtures finally made lamps widely accessible in the 1840s, by which time brighter gas lighting was becoming more frequently used in shop windows and public street lighting.

There was as yet no police force in these cities. Nightwatchmen were volunteers supervised by the daytime constables. These constables were entrepreneurs who would charge for their services, or who could be hired as private protection forces by wealthier groups of citizens: they were under no obligation to help those too poor to pay. The constables and watches wore no standard uniform, and historians report a fair amount of public suspicion that the men hired to protect upstanding citizens from crime and vice too often visited the bars and brothels themselves.

Transportation

Public transportation was not a feature of early nineteenth-century life in America. Historian Thomas Bender calls these early urban centers “walking cities,” indicating that the cities could not sprawl farther than a person could comfortably walk: they were limited to a few miles in diameter. Those with the money to do so could hire a hackney coach, a privately-owned horse-drawn cart, for short-distance travel, or a stagecoach for longer distances.

In 1829, however, New York City started a new American trend, adopting from its English inventor the “omnibus”: a twelve-seat horse-drawn wagon which traveled a fixed route along a city street, letting passengers on and off at intervals. The first one ran along lower Broadway. The other major cities quickly began to feature omnibuses as well, although like the street lights they were essentially privately-owned businesses. City governments granted omnibus companies exclusive rights to run services along particular streets. These carts were uncomfortable and slow-moving on the rough streets; only “one resident in twenty-five used this form of transport on a daily basis [even] in 1850” (Jackson).

Mixed-use city streets

Apart from their focus on the wharves, these cities were not organized into business and residential districts. Work and home life had not yet become entirely separate spheres. People ran businesses out of the same buildings in which they lived. An eighteenth-century system of apprenticeship still existed, in which a young man would live with the employer whose trade he was learning until he was ready to take over the business or start his own. Because the average citizen had to move through his or her daily routine on foot, every part of the city had to provide shopping, work, and residence. People from the upper and lower classes moved in the same public spaces, and “residential segregation by class and ethnicity was limited” (Bender).

Public health: water and sewage

Chicago developed from a farming village to a metropolis of over 1.5 million people during the 1800s, and its population fought disease throughout the century because of its poor water quality. Like people living in the other major cities, Chicagoans bought their water from privately owned water-delivery carts in the early 1800s. Their water was hauled from the river flowing through the town. But this river was quickly becoming polluted, in part by the farm animals, which were kept in the alleys of the young city, dropping manure in the streets, and which, when dead, “were piled along the waterfront” (Jones and Walker) – but also in part by human waste. Chicago was building itself on marshy ground that was too low-lying to drain properly: pit toilets contaminated nearby wells, and open ditches drained waste water directly into the slow-moving river. By the mid-1850s, Chicago citizens were dying of cholera at the rate of 60/day, and “the city’s streets were lined with coffins” (Jones and Walker). The city government gradually assumed responsibility for water and sewage control, and massive engineering efforts in the latter half of the nineteenth century included raising the street level by more than two meters and constructing an underground tunnel to draw water from far out in Lake Michigan. Nevertheless, even in 1880 the booming city population still suffered severely from smallpox, dysentery, and typhoid (Jones and Walker). (SB)

![]()

|

| Dead horse in a gutter |

Works Cited

Bender, Thomas. “The Reader’s Companion to American History – Urbanization.” Houghton Mifflin College Division. http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_088600_urbanization.htm.

Jackson, Kenneth T. “The Reader’s Companion to American History – Public Transportation.” Houghton Mifflin College Division. http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_072000_publictransp.htm.

Jakle, John A. Illuminating the American Night. Baltimore: John Hopkins UP, 2001.

Jones, Steve and John Waller. “Chicago Public Library Digital Collections – Down the rain.” www.clipublib.org/digital/sewers/sewers.html.

Teaford, Jon C. “The Reader’s Companion to American History — City Government.” Houghton Mifflin College Division. http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/rcah/html/ah_016800_citygovernmen.htm>.

Works Consulted

McSwain, James B. Review of Sara E. Wermiel’s The Fireproof Building: Technology and Public Safety in the 19th-Century American City. Nov 2000. Nov 14, 2005. www.eh.net/bookreviews/library/0313.shtml.

Morrison, Donald. “Making Cities Work: How Engineers Transformed Late 19th-Century American Urban Centres.” www.eng.nsf.edu/mr/ret_2002/making_cities_work.pdf.

Osborn, Tracy. “Teacher’s OZ Kingdom of History – 19th-Century America.” July 11, 2005. Nov 14, 2005. www.teacheroz.com.