Modernism and Sound

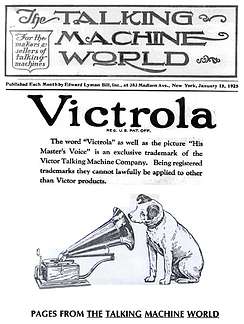

Between 1905 and 1929, the phonograph and radio trade journal Talking Machine World was published in the U.S. The “talking machine” was an early slang term for the phonograph, and the journal title indexes both the novelty and pervasiveness of new sound technologies in this period. A host of modern technologies emerged in the early twentieth century, including the mechanical phonograph (available from 1888), early silent film (beginning in 1895), transatlantic wireless telegraphy (debuting in 1901), the electric phonograph (widely accessible by the mid-1920s), broadcast radio (standardized in 1922), and synchronized sound film (available by 1926-27). Talking Machine World was one of many trade journals to register the technological and cultural terrain of emergent sound media, a terrain that was also registered and constructed in popular magazines, public spaces, newspapers, concert halls, novels, poems, and plays.

Journal cover, 1925.

Journal cover, 1925.

Technologies and Modernist Writing:

Writers of the early twentieth century responded to and participated in contexts of modern society (including new media and technology) in multiple ways in their literary work– with textual play of multiple voices, sounds, and perspectives, with the construction of sequences, with disruption of standard syntax and textual form, with fragmentation and assemblage, with the use of multiple registers of language including day-to-day phrases and the language of advertising, and with texts that resist closure and emphasize their own mediation. Many of these strategies are identified with “modernist” writing, which is a useful but contested literary category much like “Romanticism.” Modernism is often referred to as writing that disrupted Romantic, realist, and sentimental conventions (though it also engaged with these conventions) from about 1900 through World War II. Movements such as surrealism, futurism, vorticism, imagism, and “objectivism” are associated with modernist writing, as are constellations such as the Bloomsbury group in England, salons in Paris and activities surrounding the Shakespeare and Co. bookstore in Paris (which published James Joyce’s Ulysses), and “little magazines” such as Poetry and the Little Review in the U.S.

Texts and poetics of the early twentieth century draw from and contribute to the context of technological innovation. American poet William Carlos Williams, for example, wrote that a poem was a “machine made of words,” drawing attention to writing as technology and to the technical and processural components of poetry. Literary critic Carrie Noland reminds us that it would be “historically inaccurate and theoretically obtuse to insist that poems reflect technological innovations” in a direct or predictable manner, but argues it can be demonstrated that modern writers are “acutely aware of their situation within a broader field of cultural practices” and that certain poets engage and employ phonographic, electronic, and later cybernetic technologies to broaden the range of the poetic voice (7).

Williams and other modernist writers, working in the same cultural context that produced new technologies and media systems, both helped to characterize the emergent media in their writings, and developed modes of writing that ran parallel to modes of representation being developed for radio broadcasts or films. In this vein, American poet Gertrude Stein wrote that in her early textual portraits of Matisse and Picasso (1912), she “was doing what the cinema was doing, [she] was making a continuous succession of the statement of what that person was until [she] had not many things but one thing” (qtd. in Stein Selected 328). The charged literary experimentation of the modernist period responds to, and helps to characterize, the conditions of urbanization, changed modes of communication, and the functions of new technologies.

You can listen to Stein reading her portrait of Matisse, recorded in NYC in winter 1934-1935 and hosted by PENNsound, here: http://media.sas.upenn.edu/pennsound/authors/Stein/1935/Stein-Gertrude_Matisse.mp3

You can listen to Williams reading his poem “The Yellow Flower,” recorded at the 92nd St. Y, NYC, Jan. 25, 1954 and hosted by UBU Sound, here: http://www.ubu.com/sound/wcw.html

How would you describe the experience of listening to these recordings? What phrases or words stand out? Does listening to a written text shift your reception of the language in any way? How would you begin to write about, or write in response to, a recording or a broadcast of a reading?

Sound play and Radio writing:

In their literary writing, modernist writers experimented with forms and modes invoked by new sound media, and engaged questions about representation, voice transmission, and mediation. Sound artist and theorist Douglas Kahn notes that “the mere promise of technology” recharged early modernist endeavors, and that by the late 1920s artists “confronted changed conditions led by the technical possibilities of [implemented] audiophonic technologies,” such as sound film, radio, microphony, and amplification (12).

Writers of the modernist period experimented with emerging sound technologies through recording their poetry, listening to readings on records or radio programs, writing radio drama, and broadcasting lectures and creative work on the air. Many prominent writers of this period engaged in radio broadcasting: American poet T.S. Eliot broadcast lectures regularly on the BBC in London beginning in 1929; British writers Virginia Woolf, Rebecca West, and Vita Sackville-West broadcast various programs on social, political, and literary topics; and American poets H.D., Williams, and Edna St. Vincent Millay read and discussed writing on the air.

Writers of the modern period also engaged new media contexts and formats to propel creative work in multiple directions. In 1924, American poet Ezra Pound discussed radio (“where you tell who is talking by the noise they make”) as a source for the form of his Cantos XVIII and XVIX (qtd. in Terrell 75). These two sections of his long Cantos sequence assemble details from various speakers and sources on the economy of weapons manufacture, business fraud, and ideas of revolution to construct what literary critic Guy Davenport refers to as a “deliberate incoherence of particulars” (Davenport 204). In 1933, Italian futurists F.T. Marinetti and Pino Masnata’s wrote a proclamation titled “La Radia,” which claimed that creative acts motivated by radio technology should include “struggles of noises and of various distances” (qtd. in Kahn 268). James Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake (1939) also invokes radio tropes; literary critic Jane Lewty discusses how Joyce uses radio or “the ether” as a unifying device in the novel, and how radio advertising and noise and are woven throughout the text.

Other writers engaged radio for politically-motivated work: Pound’s fascist speeches on Italian radio leading up to World War II, and poet and dramatist Archibald MacLeish’s anti-fascist speeches and radio dramas are two examples of opposing ideological broadcasts. Radio historian Gerd Horten notes “unprecedented growth of radio news programs” in the late 1930s and mid-1940s; where previously news had remained the domain of newspapers, the public now began to receive more news on radio than in papers (Horten 13). MacLeish, who thought of radio as generating a potentially wide new audience for both literary work and political influence, took up the radio news format for his drama The Fall of the City (1937), which was the first radio verse play ever aired. The Fall of the City is written as a news broadcast, employing, MacLeish writes, “the everywhere of radio as a stage” to portray a European city on the brink of destruction with the change yet to fight back (MacLeish 68). Actor, director, and radio producer Orson Welles played the part of the “announcer” in the radio production, repeatedly asking the audience to “listen” over the “swelling roar of the crowd” to a messenger who brings news of impending invaders (81-3). MacLeish’s radio drama worked with aural design, attempting to portray scenes via aurally-attuned language, multiple voices, and sound effects.

The mix of voices transmitted via radio in MacLeish’s radio play is one kind of assemblage, a mode with which modernist writers experimented both on the air and on the page, producing innovative representations and portraits that circulated in the technologically-charged early twentieth-century milieu. (BH)

You can listen to a recording of the Columbia Workshop production of MacLeish’s play (from 1937) hosted at Andrew Listfield’s playlist at station WMFU, here (click the “listen” button under the Fall of the City title, the first item in the Track column): http://wfmu.org/playlists/shows/13098

Works Cited:

Davenport, Guy. Cities on Hills: A Study of I-XXX of Ezra Pound’s Cantos. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1983.

Horten, Gerd. Radio Goes to War: The Cultural Politics of Propaganda During World War II. Berkeley: U California P, 2002.

Kahn, Douglas. and Gregory Whitehead, eds. Wireless Imagination: Sound, Radio, and the Avant-Garde. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994.

Lewty, Jane. “Aurality and Adaptation: Radioplay in Ulysses.” Hypermedia Joyce Studies. 6.1 (2005). http://www.geocities.com/hypermedia_joyce/lewty2.html.

MacLeish, Archibald. The Fall of the City: A Verse Play for Radio. New York: Farrar and Rhinehart, 1937.

Noland, Carrie. Poetry at Stake: Lyric Aesthetics and the Challenge of Technology. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1999.

Stein, Gertrude. Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein. Ed. Carl Van Vechten. NY: Vintage, 1962.

Terrell, Carol. A Companion to the Cantos of Ezra Pound. Berkeley: U California, 1980.