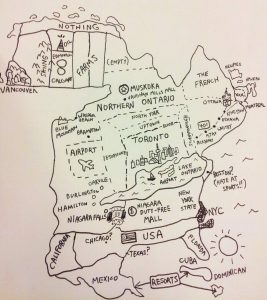

A tongue-in-cheek piece of Canadian mapping centering on Toronto (famously “the centre of the universe”), the one-time metropolitan home of Eli Stands Alone and, incidentally, the stomping grounds of Canadian critic Northrop Frye.

Hand in hand with the ferocious humour of Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water is, I would suggest, a deep concern for the sacred. What stories and words, the novel asks, are holy and binding? Which give proper coordinates allowing us to plot the courses of our lives?

King’s title begins this conversation by evoking a formula common to treaties between governments and First Nations (Flick 158); Portland’s character in The Mysterious Warrior also testifies to his love with the phrase “As long as the grass is green and the waters run” (208). This introduces the idea of mapping (as a performative, narrative act) on several different levels. First of all, treaties have to do with establishing terms and right and, often, agreeing on geographical borders. They involve a shared trust in the sacred fiction of the words used and the lines drawn. As the CanLit “Introduction to Nationalism” says, “The borders on contemporary maps resulted from long histories of negotiations and wars among nations and nation-states to control particular territories.” To give a King-esque paraphrase, every line of the map has a story—though not necessarily an equally good one, with the same depth of historical relation to the land. Physical maps institute and fix these stories in an abstract form–maps like Bill Bursum’s bluntly named “The Map,” an agglomeration of television screens showing North America. For Bursum, The Map satisfies a (none too subtle) fantasy of panoptical control: “It was like having the universe there on the wall, being able to see everything” (128). And Bursum associates this fantasy with experience of the sacred: “It’s like being in church. Or at the movies” (129). No wonder: his holy text is Niccolò Machievelli’s The Prince, from which he’s derived the gospel of advertising (128). This example (e.g. “A Western for the Map,” Bursum decides) most explicitly shows the correlation between mapping and narrating—especially in damaging ways (265).

The other way in which the title suggests a kind of mapping is by invoking the land itself. Environmental processes (the growth of grass, the flowing of water) represent not only steady, dependable rhythms of the world but also the guarantors of sincerity in human behaviour. In a sense, we are mapped by the land, and perhaps even in ways that might alleviate the kind of postmodern spatial alienation described by Frederic Jameson.

The four “old Indians” periodically wander the world fixing things like the Transformer characters of Salish mythology. The four story-women find their respective ways from the beginning of the world to Fort Marion. Characters like Alberta, Lionel, and (earlier) Eli gravitate toward their original home on the reserve, while Charlie and Portland follow a vector of motion between Blossom and Hollywood. Coyote and the narrative “I” occupy an uncertain, liminal space. And then there are the complexly interwoven temporal dimensions of the novel, with its frequent retrospects and its creation stories. All in all, it might be tempting to follow Dr. Joe Hovaugh’s lead and try to make diagrammatic sense of all this movement, to tie the novel’s fluid motions to a solid “pattern” (48).

This would seem, however, to miss the point, or to miss an opportunity. In a way, even Jane Flick’s useful reading notes can act to neutralize the overflowing and unmanageable allusiveness of Green Grass, Running Water—to compromise the experience of not knowing that Professor Paterson has pointed out as a crucial part of the novel. (As a collaborative product of discussion, however, these reading notes probably end up being something congenial to the ethos of Green Grass, Running Water.)

With this in mind, I will make one tentative suggestion about the orientation of King’s mappings in the novel. As Blanca Chester notices, the Sun Dance—which is surely somewhere near the social, emotional, and spatial heart of Green Grass, Running Water—is referred to but never directly represented (49). While the content of this sacred ceremony is absent (it must not be photographed or reproduced artificially, although Latisha feels that it is not an ineffable mystery like the Trinity), its form is present as a cyclical recurrence: “in the morning, when the sun came out of the east, it would begin again” (388). Similarly, Eli never tells Lionel the reason he came home; this is left as something it’s “best to figure . . . out for yourself” (422). This is to say that the novel centres not around something (e.g. a location or knowledge) fixed, stable or given but around open, fluid practices and understandings that unfold and are negotiated in time and in community. If, as Chester argues, King brings a multitude of stories into a dialogue in which they contextualize themselves and each other in perpetually shifting ways, then there may be no proper centre—just the water.

Works Cited

Chester, Blanca. “Green Grass Running Water: Theorizing the World of the Novel.” Canadian Literature 161/162, 1999, pp. 44-61. CanLit, 29 January 2015, https://canlit.ca/article/green-grass-running-water/. Accessed 18 March 2021.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162, 1999, 140-70. CanLit, 20 January 2015, https://canlit.ca/article/reading-notes-for-thomas-kings-green-grass-running-water/. Accessed 12 March 2021.

“Introduction to Nationalism.” CanLit Guides, 15 August 2013, http://canlitguides.ca/canlit-guides-editorial-team/introduction-to-nationalism/. Accessed 19 March 2021.

Jameson, Frederic. “Cognitive Mapping.” Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg, 1988, pp. 347-60. Shifter Magazine, https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://shifter-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/jameson-cognitive-mapping.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwj8hLy0qL3vAhXRJzQIHUwGCVQQFjAKegQIHhAC&usg=AOvVaw3baGi6M46nndtfFAtcg1tQ. Accessed 19 March 2021.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Harper Collins, 1993.

McMullan, Thomas. “What does the panopticon mean in an age of digital surveillance?” The Guardian, 23 July 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/jul/23/panopticon-digital-surveillance-jeremy-bentham. Accessed 19 March 2021.

“Treaties and agreements.” Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, 30 July 2020, https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100028574/1529354437231. Accessed 19 March 2021.

Verhoeff, Anna. “Performative Cartography.” Mobile Screens: The Visual Regime of Navigation, Amsterdam University Press, 2012, pp. 133-66. Jstor, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46mtwb.10?seq=3#metadata_info_tab_contents. Accessed 19 March 2021.

Image Credit

@JeffreyLuscombe. “When Torontonians draw a map.” Twitter, 23 January 2020, 7:01 a.m., twitter.com/JeffreyLuscombe/status/1220361018427265027?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1220361018427265027%7Ctwgr%5E%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.blogto.com%2Fcity%2F2020%2F01%2Fsomeone-just-drew-map-what-toronto-looks-centre-universe%2F.

Hi Connor,

This was an amazing read! I admit, I had been struggling to figure out why Eli had come back to Blossom, Alberta, but the way you summed it up, that the non-reveal is more about “that the novel centres not around something (e.g. a location or knowledge) fixed, stable or given but around open, fluid practices and understandings that unfold and are negotiated in time and in community” (Page March 19, 2021) felt like it made something click for me. Before, I had thought that perhaps Eli came back to Blossom because of nationalism ideals (being part of his Indigenous community); perhaps there is still something to there to my point, but I like leaving it as being open to interpretation, much like the openness of the entirety of King’s novel.

Speaking about maps, the image you posted about Toronto being the centre of the universe is very thought provoking. It reminds me a lot of the different map layouts you see throughout the world (depending on what country you go to) where, typically, the country you are visiting is place in the centre of the map (being the focal/highlighted point). It is very much a power move on the behalf of the countries who rearrange the World Map to situate themselves at the centre of it. I cannot help now but think about Dr Joe Hovaugh and how he attempts to seem powerful by placing himself/his institution/”his” Indians at the centre of the problem of the novel. I wonder if you, or any other readers, got that feeling that Dr Hovaugh was trying to become the “centre of power” in the novel? This is despite being a fairly inconsequential character, in my own opinion, to the events that were happening. It almost seems to be a dialogue of the white man trying to become the centre of the attention despite the issue not being about them.

Be interested to hear your thoughts. Thanks.

~Cayla

Hi Cayla,

Many thanks for your comment–and for citing yours truly so diligently, which warms the cockles of my heart! I agree: maps are so interesting, and often bound up in imperialist power of some sort. Sometimes they seem to be showing us not just realistic depictions of land or geographical (a significant claim in itself) but also whole ways of imagining the universe. I believe there are medieval (European) maps that make the Holy Land the centre of the world, writing a vision of spiritual power and influence–and of physical movement and pilgrimage–into represented space. I’m no expert, but I think the age of European colonialism was an important one for cartography.

To respond to your question: absolutely–I hadn’t thought of that. Hovaugh surrounds himself with the authority of “the book” and countless maps and documents, trying to establish for himself a controlling, panoptical perspective similar to Bursum’s (a God’s-eye view). Running against this, I think, is King’s deliberate diminishment of him: he shrinks behind his massive desk, often seems quite muddled, and frequently feels threatened by the reality of “untamed” land and space (no doubt a take on Northrop Frye and his troubled perception of the “wild” Canadian landscape). So yes, I’d agree that his efforts of interpretation amount to an attempt at mastery or centrality. And I think you’re also right to point out that he is, in a way, extraneous and oblivious to what’s really going on; he’s caught up in files (and contemplation of his garden) so that he misses the collaborative and conversational understanding that, say, Babo Jones is shown to have in her rapport with the four “old Indians.”

Thanks and all best!

Connor