I decided to dive deeply into pp. 389-97 of Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water. Here we go!

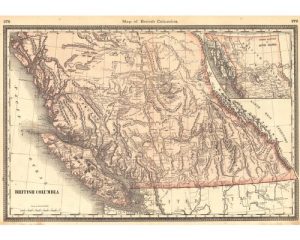

P. 389: A concentrated allusion to the critical practices of Northrop Frye, and thence to Biblical hermeneutics (and beyond?). Dr. Hovaugh (whom we’ve identified both as Frye and Jehovah) sits “in his hotel room in a sea of maps and brochures and travel guides.” This is an enclosed “verbal universe” in which the interpreter occupies himself in the comparison of the immanent qualities of texts: “he consulted the book and then a map, the book and then a brochure, the book and then a travel guide.” It seems significant that Hovaugh’s textual world is dominated by tourist kitsch—tourism being a product of consumer capitalism and its colonial exploits.

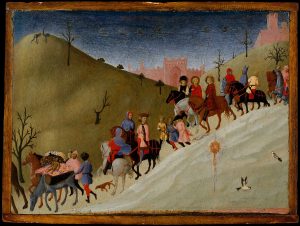

The “star,” one of the signs Hovaugh plots onto his graph—Frye had a highly diagrammatic mind—recalls the story of Jesus’s nativity: the three magi, or “wise men,” followed a star westward to pay homage to the newborn Jesus, a story often taken to signify the allegiance of all nations and peoples. King offers a somewhat inverted story: Hovaugh himself is a white Christian “wise man” following the star of a rather different “virgin birth” (or, at least, conception)–Alberta’s pregnancy, which seems to be somehow caused by Coyote.

Hovaugh’s levels of meaning or interpretation (“literal, allegorical, tropological, anagogic”) refer to the different modes of meaning ascribed to the Bible by St. Thomas Aquinas and retooled in Frye’s rather ingenious “Theory of Symbols.” These categories attempt to account for the polysemy (or the presence of many possible meanings) in a word, image, or literary work, positing various planes of literal/historical and spiritual meaning. Hovaugh’s process of interpretation is a notably “self-assure[d]” and insular activity, contrasting with the “old Indians”’s collaborative action and narration.

“Tomorrow. . . . Tomorrow and tomorrow. . . . And tomorrow” cannot help but evoke Macbeth’s famous soliloquy in Act 5 Scene 5 of Shakespeare’s play (Frye was a legendary lecturer on Shakespeare and Eli Stands Alone wrote a book about him):

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time. (19-21.V.5)

Perhaps this suggests a degree of fatalism in Hovaugh’s projections—a desperate and futile attempt at security in a world whose outcomes cannot be singlehandedly controlled.

Finally, “Parliament Lake” links the point of crisis with the Canadian government and its often inequitable relationship with Indigenous people, of which the Grand Baleen Dam is an reminder. (Perhaps Hovaugh’s three circles have a Trinitarian resonance and the “purple marker” a hint of imperial pomp? Allusive overload!) The lake also reminds us of the novel’s uniting motif of water, which is underscored by the “sea of maps and brochures and travel guides.” The image of moving water subverts even Hovaugh’s verbal universe.

P. 390: Jane Flick notes that the West Edmonton Mall indicates Charlie’s materialistic concerns (151). The Mall is “the size of a small city” and is part amusement park, part retailer—all an enveloping consumerist market of experiences and commodities. The Mall may be an opposite pole in the novel’s Alberta, and it embodies a super-capitalist lifestyle. As a “three-bedroom condo” would suggest, this is potentially a family lifestyle.

Pp. 391-6: King’s dictum that “There are no truths . . . Only stories” is characteristic, but it also bears a hint of Nietzschean “perspectivism.” This may not be a deliberate move on King’s part.

As Flick points out, Glimmerglass is a beautiful lake in James Fenimore Cooper’s The Deerslayer. As with Thought Woman and Moby-Jane, Old Woman is better able to enter into conversation with the lake itself—a conventionally voiceless entity—than with the overdetermined and narrow-minded Western heroes.

Nathaniel Bumppo finishes the series of canonical heroes with native companions. He is ironically presented as “Post-Colonial Wilderness Guide and Outfitter,” maintaining the commercial overtones of the text-centred (post-)colonial enterprise that Hovaugh also represents (392). Bumppo continually dashes behind trees, probably referring to the clichés of frontier fiction to do with preternatural hunting and outdoorsmanship skills; echoing Sergeant Cereno’s handgun (and Hovaugh’s grandfather’s rifle), Bumppo carries a “really big rifle,” which has faint (but clearly violent) phallic quality when he aims to obliterate Old Woman with it (392).

Chingachgook, a Mohican chief, is Bumppo’s loyal friend. Unlike the other “native companions” in the previous three stories, Chingachgook actually appears in this telling. His name and presence, unlike Old Woman’s, are sanctioned by the authority of the “book” when the two are challenged by soldiers. Old Woman, like her predecessors, must assume a new identity, and, again like them, she faces incarceration (396).

Bumppo’s enumeration of parallel (but unequal) “gifts” resembles Robinson Crusoe’s listing of good and bad points (King 294-5). It also taps into a deep history of European thought aligning the “Indian” with the natural and corporeal and the “White” with the civilized, intellectual and spiritual.

(I am unsure about the recurring figure of “Old Coyote” and how he relates to the Coyote who converses with the narrator. Like Coyote, he travels between stories with ease. Well, I won’t try to pin him down; I’m willing to let him run around for the time being—and perhaps someone can help me come to terms with him!)

“Whites are particularly good killers,” says Bumppo to Old Woman, making particularly plain the violence inherent in the racial hierarchizing that his story supports (393). This rendition of his character is senselessly and casually homicidal, shooting creatures “just to get it out of my system” (394). For Bumppo’s death, King exploits a common cinematic trick in which a gun is discharged but not the expected one—the hero held at gunpoint is not killed but rescued. He neglects, however, the revelation of the other shooter. Coyote’s response—”Wait, wait! . . . Who shot Nasty Bumppo?”—stands in for the reader’s reaction. “Who cares?”, replies the narrator, subverting the narrative convention (395). Coyote generally acts especially like a surrogate reader in this passage, trying to puzzle out a “deep” meaning from the events that unfold before him. His later suggestions (“Maybe there was more than one gunman. . . . Maybe it was a conspiracy”) are downright funny, if vaguely unsettling; trying to find concrete answers in the text amounts to conspiracy theorizing like that surrounding the death of John F. Kennedy (395).

King also evokes the domain of politics and legislation in the list of “killer names.” Daniel Boone, Harry Truman and Arthur Watkins are, as Flick remarks, political figures known for destructive policies and decisions, either in war or in the treatment of Indigenous peoples (163). (Needless to say, they’re also all men, which Old Woman is not. This is a recurring misrecognition.) “Hawkeye” (the “Indian” name bestowed upon Bumppo) is presented as a killer name akin to these, the implication being that violence can be inherent to certain names and acts of naming (395). (On the other hand, the adoption of a name or persona can be empowering in some ways.) As the narrator makes clear, this is not a “good Indian name” but a “name for a white person who wants to be an Indian,” rather like the real-life “Grey Owl” (395). Stories like Bumppo’s can work to both create and appropriate a mythical “Indian-ness.” King is taking some stories back by way of names and characters, and recontextualizing them in ways that reveal their hidden affinities.

Works Cited

“About.” West Edmonton Mall. https://www.wem.ca/info/about. Accessed 28 March, 2021.

Ajuha, Neel. “Colonialism.” Gender: Matter, edited by Stacey Malaimo, Macmillan, 2017, pp. 237-51. Ajuha, https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.ucsc.edu/dist/f/396/files/2014/11/Ahuja-Colonialism.pdf. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Baime, A.J. “Harry Truman and Hiroshima: Inside his Tense A-Bomb Vigil.” History.com, 11 October 11 2017, https://www.history.com/news/the-inside-story-of-harry-truman-and-hiroshima. Accessed 29 March 2021.

“Chingachgook.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Chingachgook. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Cooper, James Fenimore. The Deerslayer. Project Gutenberg, 26 January 2009, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3285/3285-h/3285-h.htm. Accessed 29 March.

“Daniel Boone.” Historic Missourians, https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/daniel-boone. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Denham, Robert. “Theory of Genres.” Northrop Frye and Critical Method, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1978. The Educated Imagination, https://macblog.mcmaster.ca/fryeblog/critical-method/theory-of-genres.html. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162, 1999, 140-70. CanLit, 20 January 2015, https://canlit.ca/article/reading-notes-for-thomas-kings-green-grass-running-water/. Accessed 12 March 2021.

Frye, Northrop. “SECOND ESSAY: Ethical Criticism: Theory of Symbols.” The Anatomy of Criticism, Princeton University Press, 1957. Blogspot, http://northropfrye-theanatomyofcriticism.blogspot.com/2009/02/second-essay-ethical-criticism-theory.html. Accessed 28 March 2021.

Grattan-Aiello, Carolyn. “Senator Arthur V. Watkins and the Termination of Utah’s Southern Paiute Indians.” Utah Historical Quarterly vol. 63, no. 3, 1995. ISSUU, https://issuu.com/utah10/docs/uhq_volume63_1995_number3/s/161824. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Halleman, Caroline. “The Five Biggest JFK Conspiracy Theories.” Town&Country, 26 October 2017, https://www.townandcountrymag.com/society/politics/a13093037/jfk-assassination-conspiracy-theories/. Accessed 29 March 2021.

“How Northrop Frye’s ‘literary cosmos’ can help us reimagine life in 2021.” CBC, 8 March 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/how-northrop-frye-s-literary-cosmos-can-help-us-reimagine-life-in-2021-1.5586648. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Isbouts, Jean-Pierre. “Who Were the Three Kings in the Christmas Story?” National Geographic, 24 December 2018, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/three-kings-magi-epiphany. Accessed 29 March 2021.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Harper Collins, 1993.

Lander, Devin, and Lauren Roberts. “Who Is the Real Natty Bumppo?” WAMCPodcasts, 30 July 2020, https://wamcpodcasts.org/podcast/who-is-the-real-natty-bumppo-a-new-york-minute-in-history/. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Marie, André. “The Four Senses of Scripture.” Catholicism.org, 11 December 2007, https://catholicism.org/the-four-senses-of-scripture.html. Accessed 28 March 2021.

“Nietzsche and the Impossibility of Truth.” New Learning Online, https://newlearningonline.com/new-learning/chapter-7/nietzsche-on-the-impossibility-of-truth. Accessed 28 March 2021.

Onyanga-Omara, Jane. “Grey Owl: Canada’s great conservationist and imposter.” BBC News, 19 December 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-24127514. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Palmater, Pam. “‘At every turn, Canada chooses the path of injustice toward Indigenous peoples.’” Macleans, 29 January 2021, https://www.macleans.ca/opinion/at-every-turn-canada-chooses-the-path-of-injustice-toward-indigenous-peoples/. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. MyShakespeare, https://myshakespeare.com/macbeth/act-5-scene-5. Accessed 29 March 2021.

Tupy, Marian. “How Capitalism Brought Tourism to the Masses.” Fee, 15 January 2019, https://fee.org/articles/how-capitalism-brought-tourism-to-the-masses/. Accessed 29 March 2021.

White, Ellen. “Defining Biblical Hermeneutics.” Biblical Archaeology Society, 2 August 2020, https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/bible-interpretation/defining-biblical-hermeneutics/. Accessed 29 March 2021.