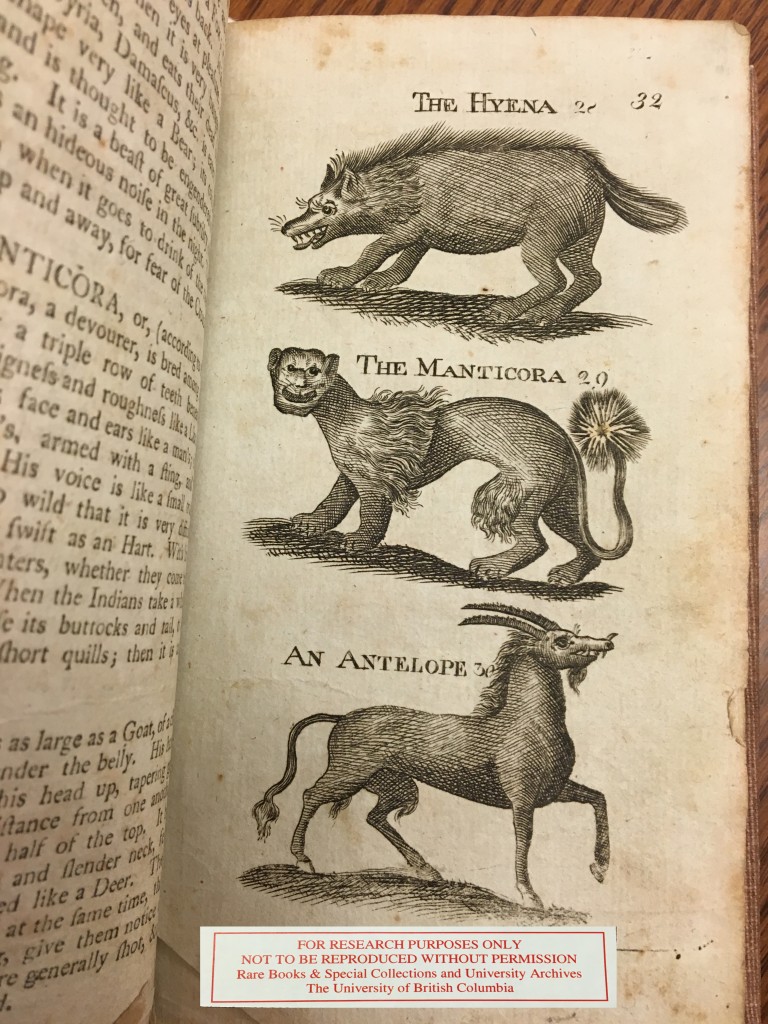

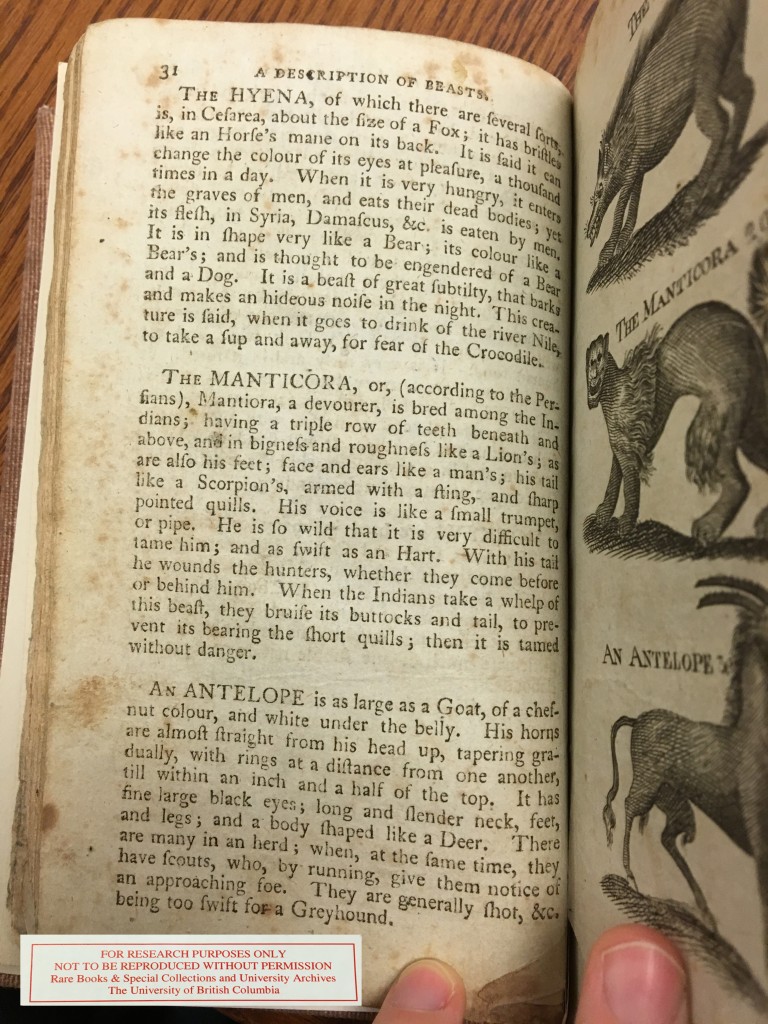

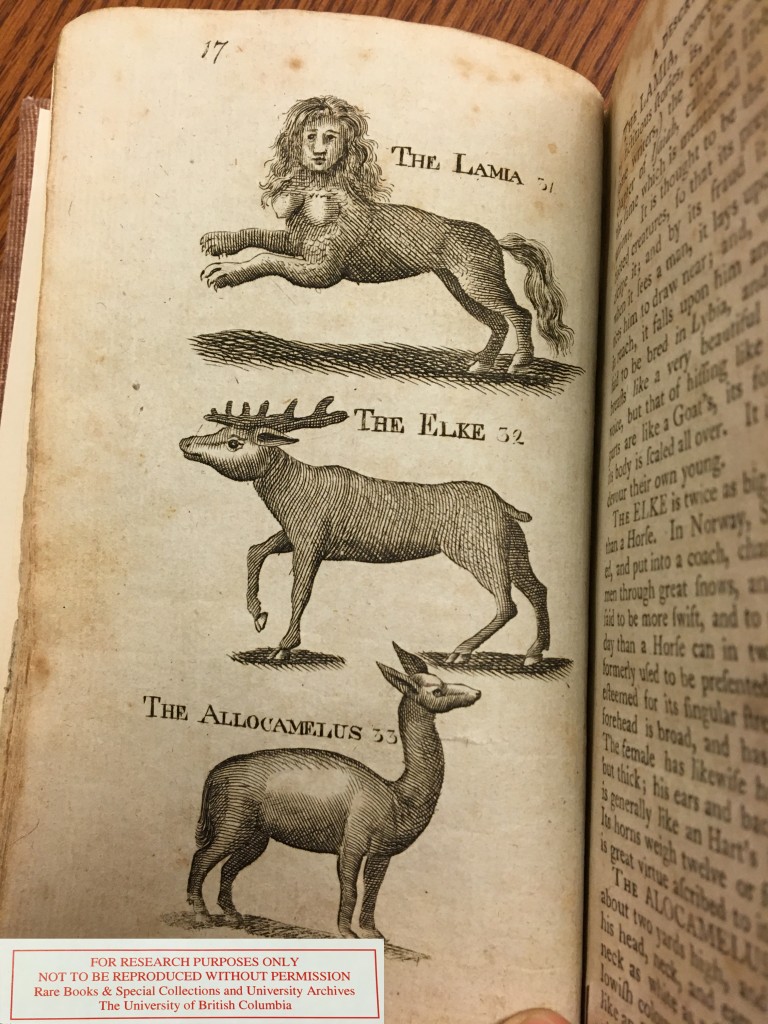

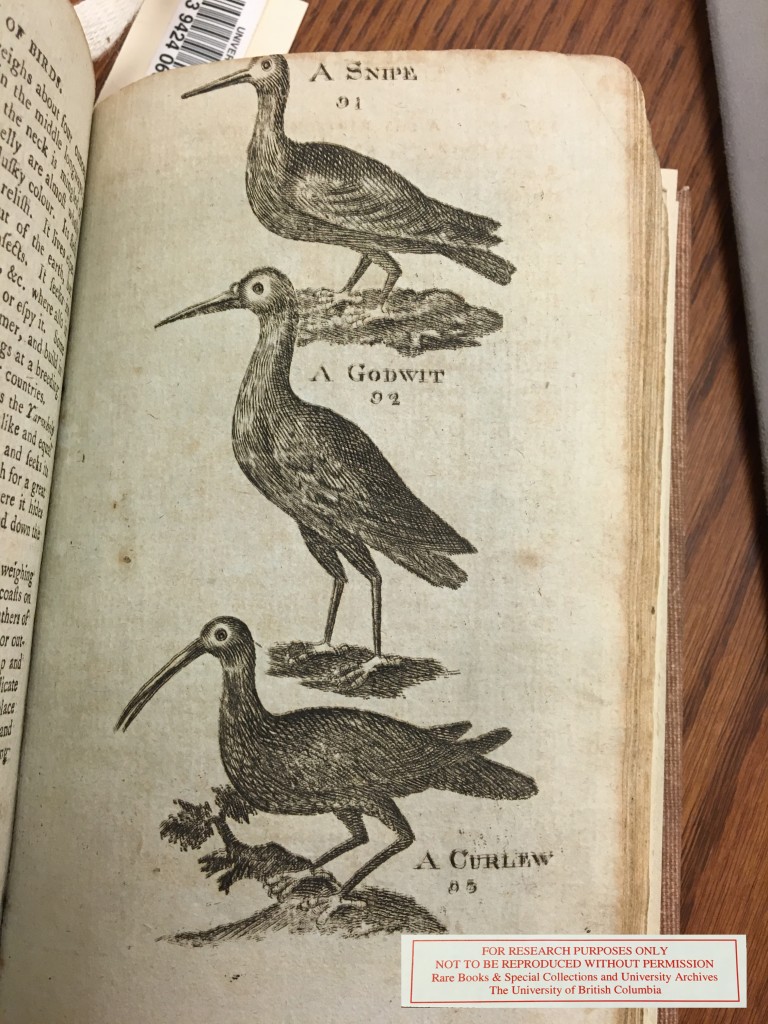

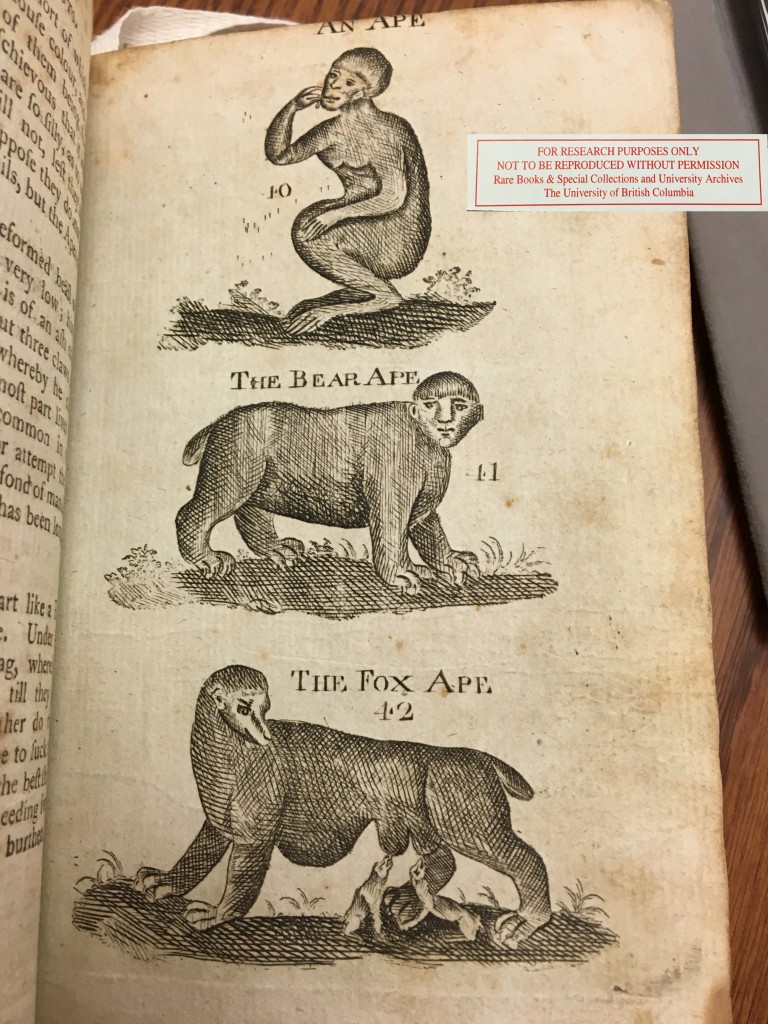

The format of the book is quite straightforward, in which one page is the text explaining the animal, and the other, illustrations of said animal. It is clear that the pages were printed separately and then bound together, for the pages with illustrations are blank at the back. This is typical of the intaglio printing process, as Boreman uses copper plates to print his illustrations. The indent around the paper is a result of pressing down the copper plates.

The animals featured in this book are beasts, birds, fishes, serpents, and insects, in that order.

Articles dedicated to Boreman are few and far in-between, but in one of the more extensive articles about Boreman, Harry B. Weiss writes:

If Thomas Boreman had anything to do with these books, he was, in all probability a compiler, one without much discrimination, because he put together observations, mistakes, worthless descriptions, etc., of naturalists, travelers, etc., as recorded in previous works. If anything good is included, it probably slipped in by mistake, and not because of the compiler’s nice perception. Boreman was interested in sales.[1]

However, I would like to argue that Boreman took care to ensure that his books were both educational and enjoyable for children. The descriptions found in A Description of Three Hundred Animals were compiled from what were thought of as reputable sources at the time, like Edward Topsell’s History of Four-Footed Beasts (1607) and Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1668), which were still widely read, although dated by the time Boreman published his books.[2]

Boreman seems to subscribe to John Locke’s theory on education and tabula rasa written in his “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) and “Some Thoughts Concerning Education” (1692). Locke believed that children are shaped by their experiences in the external world rather than having any innate qualities, and subsequently children become a result of the education they have undertaken. Boreman’s concerns about the impact of literature on children is apparent by his efforts to bring both delight and knowledge together:

I have thought fit, with short descriptions of animals, and pictures fairly drawn, (which last, experience shews them to be much delighted with,) to engage their attention. I have therefore extracted, from some of the most considerable authors, a short account of beasts, birds, fishes, serpents, and insects; which, I hope, will prove the more acceptable, there having been nothing done (that I know of) in this nature to compendiously, for the entertainment of children.[3]

A Description of Three Hundred Animals is interesting in that it not only documents real animals, but mythical beasts as well, harking back to the tradition of medieval bestiaries. The book also includes many foreign creatures to incite interest to the progress of European globalization in the 18th century.

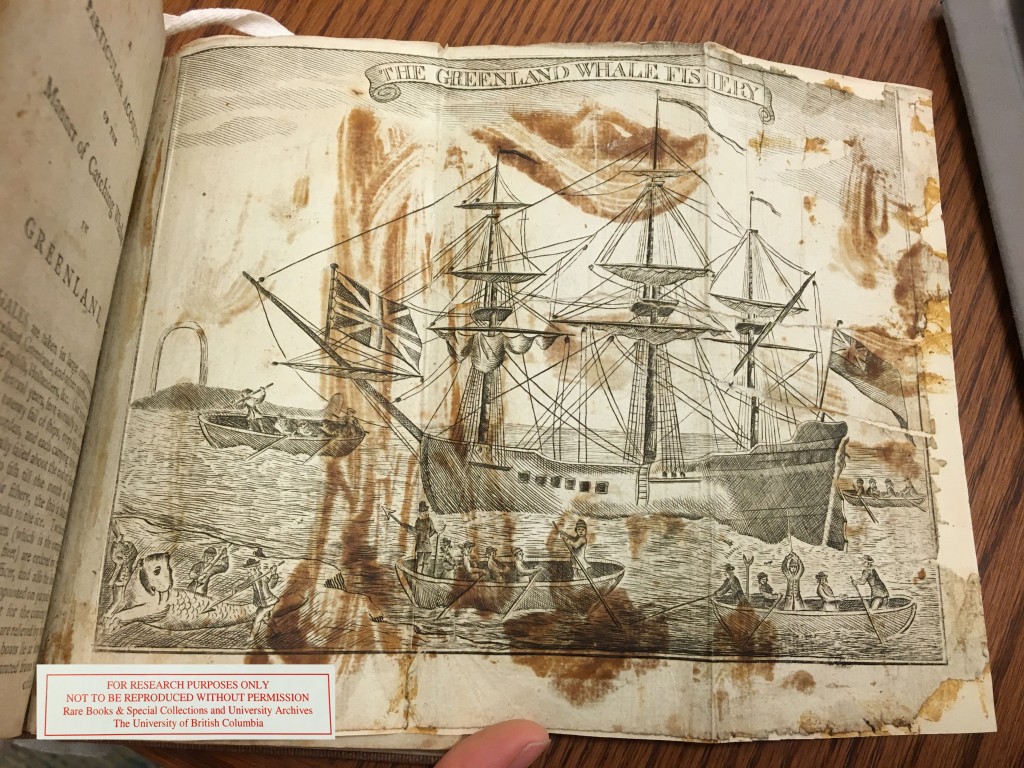

Engraving was typically reserved for expensive adult works and technical books. However, engraved illustrations allowed greater details in the pictures, and for Boreman to employ that technique further exemplifies his high regard for illustrations in children’s literature.[4] Unfortunately, the artist of Boreman’s books are unknown. The variety of poses, design, and shading in the illustrations show the artist’s care and effort:

Some even span the whole page:

Although the illustrations are well done, in RBSC’s particular book, the printing job is sloppily done at times, in which pages are cut off or blurry.

The library’s copy also has its binding replaced with a modern crisscross cloth, however, it seems that it had been left without a cover for some time, as the front and end pages are noticeably more worn out and frayed due to exposure to the elements.

[1] Weiss, Harry B. “The Entomology of Thomas Boreman’s Popular Natural Histories” Journal of the New York Entomology Society, 47.3. (1939) p.216.

[2] Zipes, Jack. “Boreman, Thomas” The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature.

[3] Boreman, Thomas. A Description of Three Hundred Animals. London: Printed for A. Millar, W. Law, and R. Cater; and for Wilson, Spence, and Mawman, 1795. p.4.

[4] Whalley, Joyce Irene. “The Development of Illustrated Text and Picture Books” International Companion Encyclopedia of Children’s Literature. London: Routledge, 1996. p.218.