Jasper’s Review: TRANSGRESSION/CANTOSPHERE

Tucked away into a heritage building Vancouver’s culturally teeming ‘Historic Chinatown,’ in Centre A, Vancouver’s International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, sits the new exhibition entitled TRANSGRESSION/CANTOSPHERE. The exhibition, which takes up the entirety of the space, is a variety of work created by the Hong Kong Exile collective in collaboration with Zoe Lam and Howie Tsui.

Tucked away into a heritage building Vancouver’s culturally teeming ‘Historic Chinatown,’ in Centre A, Vancouver’s International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art, sits the new exhibition entitled TRANSGRESSION/CANTOSPHERE. The exhibition, which takes up the entirety of the space, is a variety of work created by the Hong Kong Exile collective in collaboration with Zoe Lam and Howie Tsui.

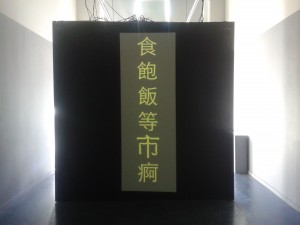

The gallery space is divided into two sections by a wall. Upon entering the gallery, viewers are greeted with a ‘found object,’ a street sign that says ‘Historic Chinatown,’ upon which projections of the Cantonese title of the exhibition are displayed. A Mahjong table sits underneath, with headphones playing a recording of Lam attempting to teach Tsui how to properly pronounce Cantonese phonetics. In the back section of the space, a thin strip of English text encircles the space on the wall at eye level. Without spaces, or punctuation, the text is, at first, virtually illegible; after scrutiny, it reveals itself to be Vancouver City policy on the urban planning of Chinatown. A white screen hangs down near one wall, upon which a pun-generator projects various permutations of Cantonese sentences in Cantonese characters.

While the exhibit as a whole can seem rather opaque upon first its encounter, with some careful and thoughtful analysis, a few prominent themes appear and run throughout the various elements in the exhibit.

First, the theme of language and accessibility arises, more specifically in the limited manner in which language can be understood across culture. What does state policy mean to someone who cannot read it? How can puns be understood when the characters themselves have no meaning to some? While this may seem obvious and superfluous, the issue of language in Chinatown and China itself is a truly loaded subject. In many provinces in China, state policy has outlawed the use of Cantonese, the language spoken by the people, in schools, in favor of Mandarin, the language of the government. The top-down indoctrination of language upon population limits cultural diversity and nuance, distances people from their cultural history, and blurs the distinctions that make a person’s own cultural identity.

The idea of language being inaccessible for some, or certain languages more accessible than others to whomever is reading them, comes up forcefully in the exhibit. When one is presented with two languages to read, one tends to gravitate towards the language that is easiest for them. Upon viewing the English text on the wall, the tight spacing and lack of punctuation, in tandem with the stiff bureaucratic diction, makes English a virtually foreign language.

But the bureaucracy of Vancouver’s urban planning in regards to Chinatown are shown to be just as culturally limiting as China’s language policies. With the text on the wall asserting that Chinatown must ‘modernize’ and ‘clean up’ to be more inviting, all the while calling it on city signage ‘Historic Chinatown,” rooting the still lively and cultural relevant neighbourhood in antiquity.

Centre A’s exhibit attempts, and succeeds, in bringing to light some of the largest cultural issues that exist today in Chinatown’s sphere.