Exhibit Confronts Culture and Language Loss: transgression/cantosphere at Centre A

A multimedia exploration of space, language and Cantonese culture, transgression/cantosphere resists processes of homogenization and “Mandarinization” in Vancouver’s Chinatown (“transgression/cantosphere”). The neighbourhood is under pressure by local city planners to diversify and modernize. Chinatown is also part of the international struggle to preserve Cantonese language and culture, currently under threat by the Chinese state. The exhibit uses visual and audio representations of Cantonese and English, in the space of Chinatown itself, to “strike back” against forces which seek to suppress the linguistic and cultural diversity of the neighbourhood (“transgression/cantosphere”). Currently on exhibit at the Centre A gallery, transgression/cantosphere is a collaboration between Vancouver-based arts company Hong Kong Exile, linguist Zoe Lam, and artist Howie Tsui.

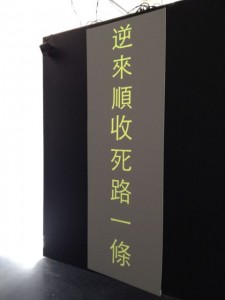

Inside the gallery, a street sign reads “Historic Chinatown,” with the words “transgression/cantosphere” projected in Chinese characters across it. A mahjong table sits to my left and a recorded voice speaks in Cantonese from behind a tall black partition. Peeking around, I see a scroll-like vertical projection of shifting Chinese characters. On the far wall, a long stream of English phrases are strung together horizontally. Curator Tyler Russell tells me that viewers observe the exhibit differently, depending on whether they can read the Chinese characters. Those who cannot understand the audio Cantonese and written Chinese often turn away from the black wall, focusing on the ‘English side,’ whereas Cantonese speakers face the other way. Dividing audiences on the basis of linguistic and cultural accessibility, the exhibit reflects opposing perspectives on what Chinatown should be, whom it should include, and whose voices must be heard.

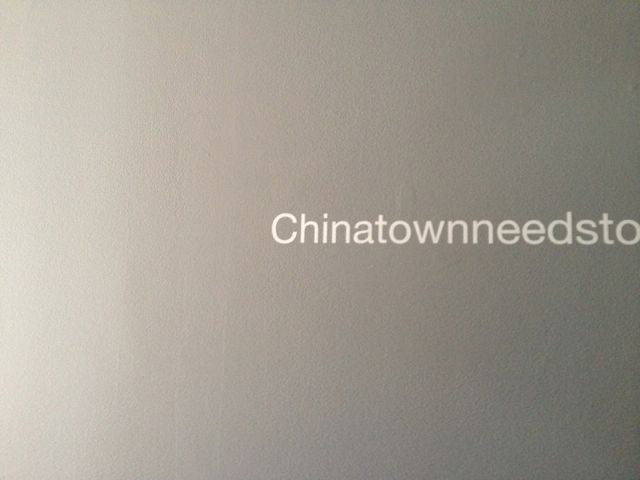

On the ‘English side,’ words are pressed together in a single line on the wall, without punctuation or spaces. The unbroken text is disorienting. Viewers must engage in a translation process, unraveling the text into meaningful ideas by inserting the natural phrase breaks. This translation mirrors the struggle of Cantonese speakers to re-translate culture and language that are undergoing “Mandarinization.” I soon discern that the text reveals a plan for making Chinatown more palatable to outsiders. It begins with a forceful “Chinatown needs to…,” listing a set of changes that will “revitalize” the neighbourhood: “greet customers with friendly and welcoming attitudes” and “attract the growing genre of new technology based businesses.” Pulled from the Chinatown Neighbourhood Plan and Economic Revitalization Strategy, these directives paradoxically assert that Chinatown must modernize yet maintain its “historic” novelty. The plan calls for the erasure of Chinatown’s distinctive cultures and languages in the greater project of ‘multiculturalisation.’ On this wall, Chinatown is emphasized as a space that “needs to –,” not a space that is. The textual presentation reflects the content; the single line has no space for diversity, opposition, or dialogue.

Though Anglophone viewers may be drawn to the English text, it soon becomes difficult to ignore the Cantonese video. For those who cannot understand Cantonese, the video is inaccessible. I initially watch the changing Chinese characters with waning interest, but when I pick up a translation key[1], I begin to make connections. Derived from Hong Kong’s recent umbrella revolution[2], some phrases have a strong political voice, such as “Justice under the glass, beaten up in the dark.” But the artists also play with the words, changing political statements into witty assertions. For example, “I want universal suffrage” becomes “I want universal garlic.” According to Mr. Russell, wordplay is central to Cantonese cultures, as the language contains many homophones[3]. In light of the Chinese state’s attempt to ban puns on television and radio (Branigan n.p.), this wordplay performs linguistic resistance.

The exhibit’s use of space situates viewers in a microcosm of Chinatown’s current conflict. As I look from the ‘English side’ to the oppositional ‘Cantonese side,’ I am caught between voices that seek to homogenize Chinatown, and others that celebrate Cantonese linguistic creativity. By placing viewers in this space of dialogue, transgression/cantosphere challenges audiences to consider the value of protecting heritage languages and cultures, the importance of resisting homogeneity, and the costs of ‘modernization.’

Works Cited

Branigan, Tania. “China Bans Wordplay in an Attempt at Pun Control.” The Guardian. 28 November 2014. The Guardian. Web. 7 Mar. 2015.

“transgression/cantosphere.” Centre A. Web. 5 Mar. 2015.

[1] Interestingly, Mr. Russell informed me that the artists debated whether or not to include a translation key. The day before the exhibit opened, they decided in favour of translation.

[2] Also known as the 2014 Hong Kong Protests, the umbrella revolution was a mass civil disobedience movement protesting the Communist Party’s attempt to pre-select Hong Kong political candidates, among other things.

[3] Homophones are words that are spelled the same but vary in meaning. For example ‘rose.’