Linguistic Tensions in the Cantosphere

On March 7th, I visited transgression/cantosphere at CentreA, a gallery for contemporary Asian art in Chinatown. The exhibit is the work of Hong Kong Exile, an interdisciplinary art company, along with linguist Zoe Lam and local artist Howie Tsui.

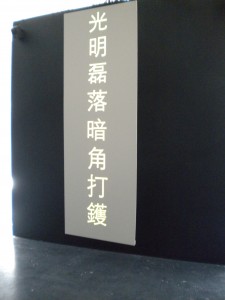

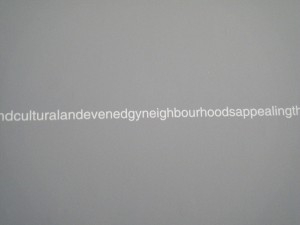

The exhibit is immersive, combining projections, audio, text and, objects. Upon walking into the gallery, you are greeted by a bright green road sign that says, “Historic Chinatown” onto which has been projected the characters for the show’s title. To the right of the door sits a mahjong table where, using the provided headphones, you can sit and listen to recordings of Howie Tsui practicing Cantonese. As you walk past the dividing wall, your eye is drawn to a single continuous string of English words (statements about Chinatown and cultural loss) printed at eye height on the walls. The room also features a quartet of fancy local spa products on a wooden shelf and a vertical screen with projections of various phrases in Cantonese, individual characters abruptly changing like symbols on a slot machine. Over speakers, one can hear layered voices reading out the phrases on the screen. This is interspersed with the ‘click clack’ of mahjong tiles and protest chants from the “Umbrella Revolution.”

During my visit, I spoke with Tyler Russell, the curator of CentreA. Russell mentioned that the artists had thoroughly debated about whether to include English translations of the Cantonese phrases as part of the exhibit. Ultimately, the artists did decide to do this, as the exhibition guide includes just such translations to assist guests. This guide piqued my interest.

Using the guide, I could observe how the changes in pronunciation altered the entire meaning and writing of the Cantonese phrases on the screen. For example, with a barely perceptible shift in tone, the phrase for “I want genuine universal suffrage” became “I want genuine universal grandchild” or a variety of other phrases. For many white Canadians like myself, the difference between Cantonese and Mandarin may seem inconsequential—we mistakenly collapse them into simply “Chinese”—however, transgression/cantosphere reminds us of the betrayal of translation and the potential meanings that are lost in the movement from one language to another.

The juxtaposition between English and Cantonese also made me reflect upon the ways that languages migrate and how languages have sometimes come into violent contact with each other. Through the imposition of English and French by European colonial forces in Canada, hundreds of languages have vanished from this land, and still do, due to assimilation processes. In the string of English words printed on the three walls (the spaces between the words removed so as to unsettle the reader) the “speaker” describes the need to make Vancouver’s Chinatown “more multicultural,” that is, available to investment by upper-class English speaking people and not Cantonese speakers (“Current Exhibition”). With my ‘trusty’ translation guide in hand, I felt very aware of these tensions.

What is the value of a language? What are the dangers or benefits of translation? How can a community grow through time without losing a sense of cultural integrity and diversity? transgression/cantosphere grapples with these questions and makes a strong case for the protection of Cantonese culture both in China and Vancouver.

– By Arielle Spence

Works Cited:

“Current Exhibition.” Tyler Russell. CentreA. CentreA, 22 January 2015. Web. 13 March 2015.