Material legacy at the “Magic Hour”

I was at the Nikkei Centre this weekend and, finding myself with a few free minutes, decided to pop in and see the current exhibit in the gallery, “Magic Hour”, curated by the Instant Coffee Artist Collective.

Here’s what the Nikkei Centre website has to say about the show:

The Instant Coffee Artist Collective takes an unexpected and innovative look at the gems from our permanent collection. Magic Hour is the name of that time just after sunrise or just before sunset, and we are excited to tease out the magic in our archives.

Instant Coffee has filled the modestly-sized gallery space at Nikkei with an eclectic selection of items, ranging from vinyl albums which visitors are encouraged to play on a record player provided, to archival videos of interviews with Japanese Canadian elders, to paintings by Japanese Canadian artists, and even a Buddhist family altar. One wall of the gallery is painted with a playful orange and yellow “Magic Hour” logo, reinforcing the eclectic ambience.

There doesn’t seem to be any rhyme or reason to the exhibit, which I think is exactly the point. The Nikkei Centre doesn’t have a large permanent collection on display, so many of these items – and certainly many more like them – must spend long periods of time in storage, gathering dust.

A few items stand out: the Buddhist family altar, heavily ornamented in gold, being the first. Word around the centre is that it was packed up by the family who owned it in 1942 and brought to one of the self-supporting camps in the BC interior when the Japanese Canadian community was forcibly relocated, and brought away again when the family left. Many of these items, including a modest wooden table and chair set labelled as being from one of the internment camp schools, survive from the 1940s period which saw the Japanese Canadian community forced to perform a very specific kind of small-scale migration. It is also worth noting that very few families would have been able to carry large, heavy objects like the family altar with them; those who could not afford to go to the self-supporting camps had very strict restrictions on luggage and would certainly have had to leave valuable family items like this behind.

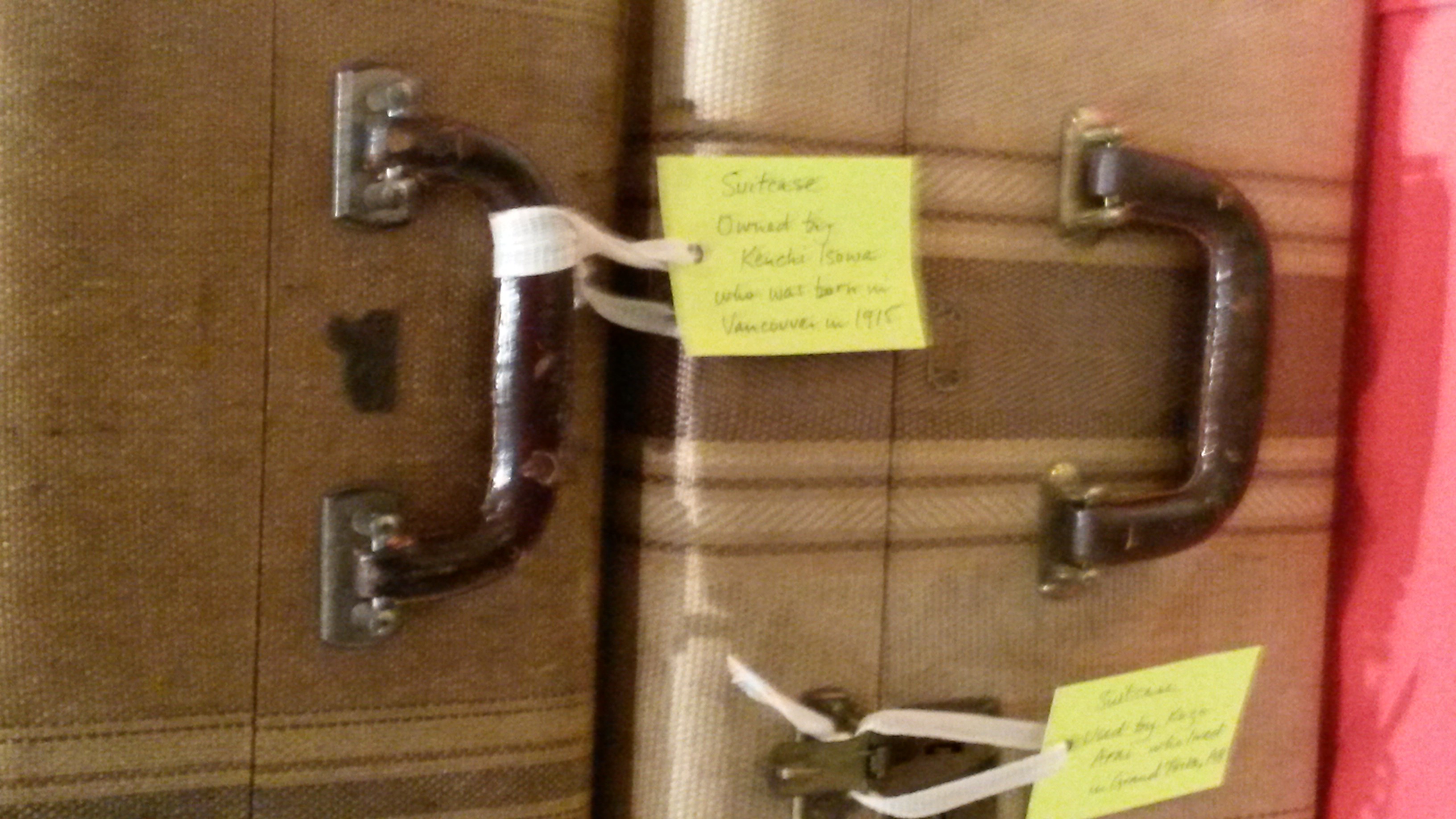

The items that most potently represent this loss are the stacks of old-fashioned luggage in the back corner of the exhibit. Each piece has a large yellow tag attached with information about the time period and/or donor; each suitcase has a different donor. One label reads: “Suitcase owned by Kenchi Isowa who was born in Vancouver in 1915”. While this kind of biographical detail of the owner is not included in every label, it is also not unique or out of line with the information on the majority of the labels. For the generations of interned Japanese Canadians who lost nearly all of their material possessions, the suitcase seems an appropriate candidate for the representative material artefact of the community, a symbol of their lived experience of confined migration.

In this context, markers of sedentarism become means of asserting legitimacy within the nation-state: Isowa was “born in Vancouver in 1915”, not a migrant, and yet was almost definitely one of the thousands who were forced to migrate away from the coast, having been marked by the government as an enemy alien, a migrant from outside the boundaries of what was considered culturally Canadian. The table and the altar are cultural artefacts from the community which were not designed for mobility, but forced into it when Japanese Canadians were uprooted, and again when the camps in the interior were closed down. These mostly innocuous-looking objects, both those designed to facilitate migration and those which by their size and weight would impede it, have lived to tell the tale of migration. Whether brought from Japan, purchased in Vancouver, or made in the interior of British Columbia, they have reached an end point to their journey in the Nikkei Centre’s archives. The survival of material objects from this period in history, against odds, becomes a means for the Japanese Canadian community to assert its legitimacy as a historical presence in Canada, quietly, among the array of items that fill a cultural archive.

Works Cited

“Magic Hour by Instant Coffee”. Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre. Nikkei Centre, n.d. Web. 11 Mar. 2015.