Teaching Language in Hong Kong Exile’s Centre A exhibit

![]() (transgression/cantosphere), at the Centre A gallery in Chinatown, features the Cantonese language at a time when it is coming under threat, not only due to legislation being imposed by the Chinese government, but also in Vancouver’s Chinatown, where Mandarinisation and urban revitalization are threatening to overcome the traditionally Cantonese area. It was created by local artistic collective Hong Kong Exile, in collaboration with visual artist Howie Tsui and linguist Zoe Lam.

(transgression/cantosphere), at the Centre A gallery in Chinatown, features the Cantonese language at a time when it is coming under threat, not only due to legislation being imposed by the Chinese government, but also in Vancouver’s Chinatown, where Mandarinisation and urban revitalization are threatening to overcome the traditionally Cantonese area. It was created by local artistic collective Hong Kong Exile, in collaboration with visual artist Howie Tsui and linguist Zoe Lam.

I would like to acknowledge here that I do not speak Cantonese, nor do I have any significant familiarity with any dialect of Chinese. Someone who does know Chinese and/or Cantonese in some form would probably have a very different experience of this exhibit, but I can only speculate on that based on what the exhibit and my related research has taught me.

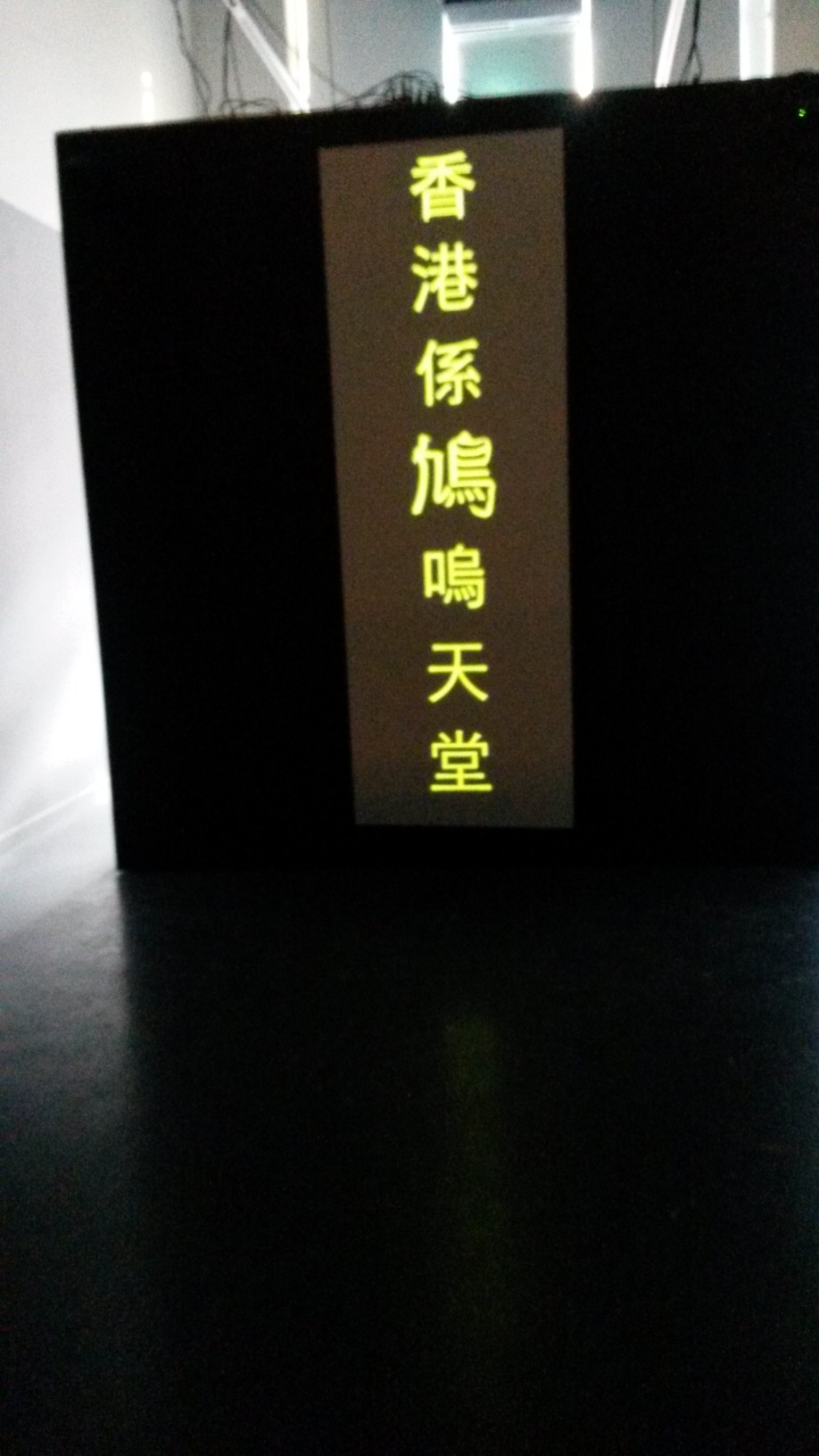

The performance-based background of the core artists in Hong Kong Exile shows in their careful staging of the gallery space: the already limited space of Centre A has been walled off further, with a partial wall separating a small entrance area from the rest of the exhibit behind. The most prominent aspect of the exhibit is a projection display onto a screen hanging on the back of the partial wall, where four to five Chinese characters are displayed at a time in a vertical scroll layout, showing one of a handful of set phrases at a time and creating variations on them. The variations are created by altering a single character, which is read out in the accompanying audio as it appears. The characters replacing one another in rapid succession are pronounced with the same syllable, but different intonations.

With yellow characters projected on a black backdrop in a small room with dimmed, flickering lights, the effect is eerie, even alienating (see image). However, the entrance area of the exhibit offsets this effect. First of all, there are pamphlets available with English translations of each of the set phrases, as well as their variant forms. The variant phrases were created by a pun generator: “I want genuine universal suffrage” can become “I want genuine universal garlic” with the change in tone of a single syllable. The pamphlet also encourages guests to “inquire to gallery staff” for “more detailed translation[s]”. The staff member I spoke to explained the importance of tones in Cantonese, where there are twelve tones instead of four in standardized Chinese.

But a less conventional choice than a translation guide is the mahjong table set up at the front, equipped with headphones through which visitors can listen to a recording of people conversing in Canadian English and practicing pronouncing different tones of Cantonese syllables. The conversation is casual and congenial, and altogether sounds like something that could take place hanging out around a mahjong table with some friends. The listener is not acknowledged as audience, but rather accepted implicitly as co-learner of the different tones.

A statement on Centre A’s website explains that in the exhibit, the five creators “grapple with local and international pressures on their mother culture”. Other than linguist Zoe Lam, all of the creators identify themselves as Vancouver-based artists. But the recorded conversation is more than diasporic people learning the nuances of their heritage language: by being shared with the visitor, it becomes a way of teaching all those who come to the gallery, regardless of heritage, and inviting them to share knowledge. Without listening to these lessons at the entrance, to a non-Cantonese speaker the projection display would seem forbidding and opaque, but the chance to listen in on a collective learning experience primes the ear to distinguish the tonal shifts and appreciate the meanings being created, if not necessarily grasping them without the written guide.

While translations are made available to visitors, they are acknowledged as insufficient by the note encouraging visitors to inquire further. Moreover, the actual meaning of the phrases is sidelined in favour of attention to sound, and the (non-Cantonese-speaking) visitor is placed on a continuum towards understanding, rather than being confined to a reductive English translation. While engaging with both local and international political issues, ![]() (transgression/cantosphere) also welcomes the local, non-Cantonese-speaking community to become familiar with the traditional culture of Chinatown through language.

(transgression/cantosphere) also welcomes the local, non-Cantonese-speaking community to become familiar with the traditional culture of Chinatown through language.

Works Cited

“Current Exhibition”. Centre A. n.p., n.d. Web. 6 Mar. 2015.