The Sound of Transgression

transgression/cantosphere — Hong Kong Exile, Zoe Lam, and Howie Tsui

Centre A Gallery, January 22nd – March 28th, 2015

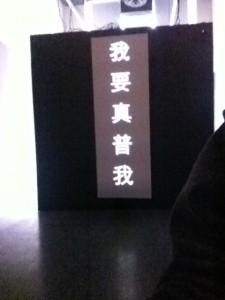

The noise of clattering mahjong tiles echoes through Centre A in their current exhibit, punctuating the sound of a woman reading. This track accompanies a central projection, comprised of a column of Chinese characters on a black background. As the track progresses, these characters change. At times, the differences are relatively simple—only a single character in the column, mirroring the alteration in the woman’s intonation. At other points, the project becomes more dramatic; the entire column rapidly switches, characters warp and buckle under invisible pressure, or the characters are immersed in flickering visual static or noise.

What is not foregrounded is that the projection is a pun generator. Each projected column is a proverb or phrase; however, these phrases shift as individual characters—and hence intonations—change. The sentence “Welcome to Chinatown,” for example, becomes “Welcome to Candyman town,” while “The hope is in the people” switches to “The hope is in the human kiss” (amidst other possibilities). For those not fluent in Cantonese, this knowledge can only be gleaned from a photocopied sheet found at the front of the gallery, which provides English translations of the various modulations.

While structured as a game of sorts, the pun generator speaks to broad political and linguistic issues in a transpacific context. As the exhibit brochure explains, a 2012 enactment in Guangdong removed Cantonese from both the media and from government and school use. More recently, the Chinese government effectively “banned” puns, regulating their use in both the media and in public life. This ban, they explained, was to prevent linguistic “chaos.” What went unsaid was that Cantonese, which utilizes a greater number of tones than the official Mandarin dialect, is effectively a more punning language. Subtle differences in intonation, as the pun generator demonstrates, can change the idiomatic meaning of a sentence, injecting humour or sedition.

In a similar light, the ongoing gentrification of Chinatown has been accompanied what the artists see as “ominous signs of Mandarinization.”[1] Here, such Mandarinization happens on a linguistic level, but also on the level of what might be seen as spatial or cultural idiom. The disappearance of stores, the destruction of historic buildings, and the ascendance of condos all threaten the Cantonese linguistic, and cultural character of Chinatown. Such a threat is emphasized by the text wrapping around the gallery walls, which pulls from a government report on the supposed economic stagnancy—and hence “necessary” development—of Chinatown.

As a response, Hong Kong Exile’s pun generator plays with idiom and tone to emphasize the productive noise of language. Here, noise or “chaos” might act as the space of heterogeneity both within, and between languages. Formed by the slippages between signifiers, puns enact the transgression of the show’s title. Yet this transgression, as the show seems to argue, can itself very quickly slip into translation, or—perhaps accompanied by the crackling static of radio or television—into the noise of transmission. The point of the show, it seems, is not to separate or isolate moments of slippage, flattening them into comprehensible and commercial homogeneity, but to amplify noise and humour as a mode of resistance.

[1] See http://centrea.org/exhibitions/current/ for the accompanying exhibit text. Unfortunately, the translations provided at the gallery do not appear to be available online.