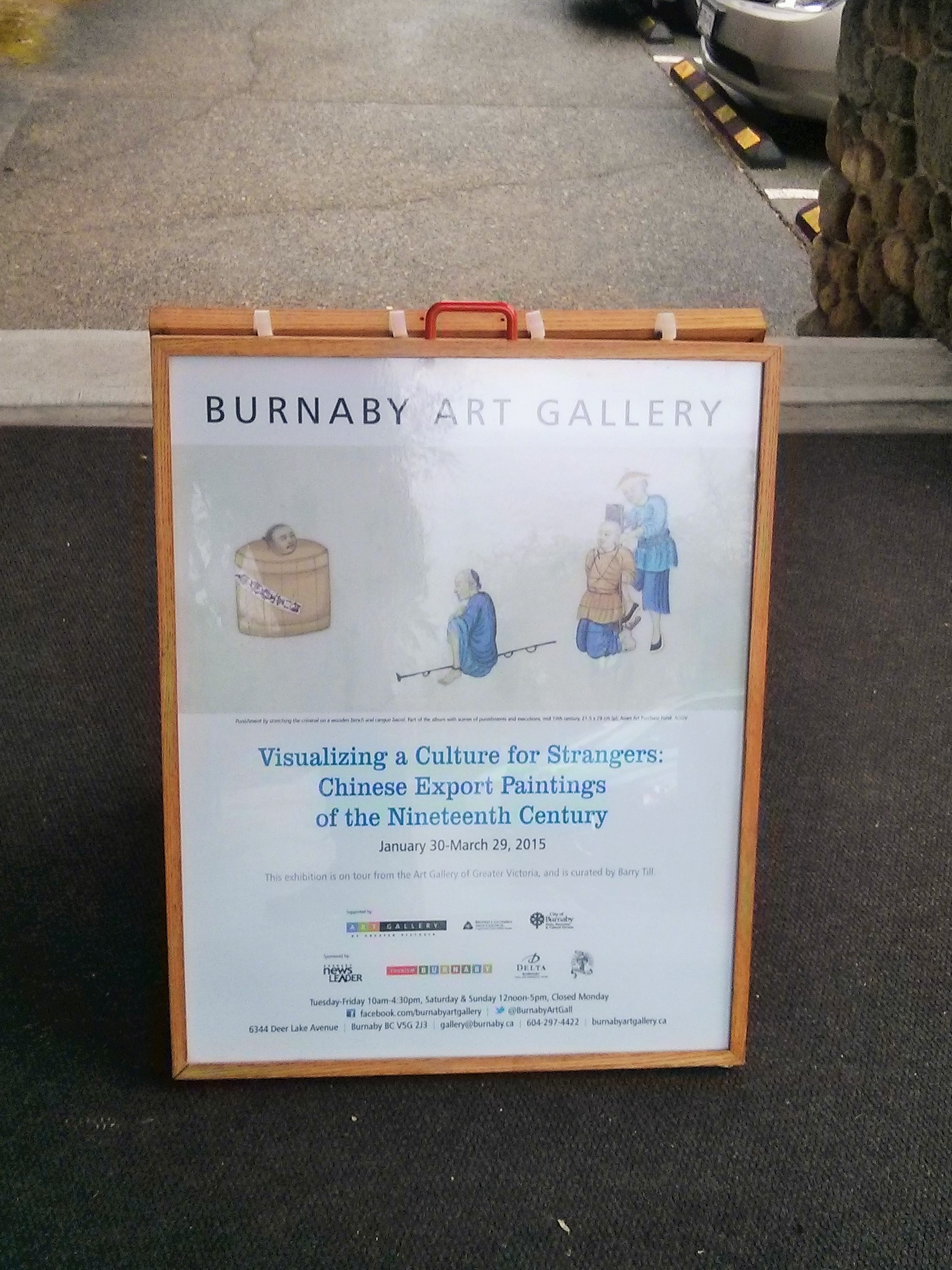

Visualizing a Culture for Strangers: Chinese Export Painting of the Nineteenth Century-Review

On loan from the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, “Visualizing a Culture for Strangers: Chinese Export Painting of the Nineteenth Century” presents a wide collection of 19th century “Export Paintings” that were mass produced across Chinese port cities and sold to traveling Western merchants.

The lesson taught in Econ 101 classes everywhere, “an excess of demand will eventually be met with an appropriate supply”, is a popular refrain in 21st century free-market jargon and it is also an apt (albeit strange) summation of the history of the paintings in “Visualizing a Culture”. Imperial trade in the 19th century facilitated the economic growth of Chinese port cities. These cities saw a massive expansion of their commercial and industrial capabilities, transforming port cities like Canton (Guangzhou) into and centers for global trade. The exhibit tells us that the mostly European merchants that arrived at these cities’ ports often rejected Chinese painting techniques but nonetheless wished to acquire records of their travels through paintings and other art. These merchants therefore demanded art that seemed to them “more realistic, painted with Western spatial forms and perspective methods”, or in short, they wanted art that adhered to their European aesthetic sensibilities. Commercial Chinese painters residing in the port cities quickly matched the demand of the Western merchants, mass producing paintings ranging from serene waterfront landscapes and portraits of various merchants and dignitaries, to a series on the production of silk.

Originally these paintings were sold and spread across the Western world, and by bringing these mass produced works back together, the curators invite reflections on the intimate intersections between art, trade, and race. One particularly provocative set of paintings, a small series of graphic depictions of corporal punishment, illustrate this quite clearly. The paintings depict violent acts such as the cutting of a criminal’s flesh piece by piece, lashing a liar with a bamboo stick, and stretching a criminal across a wooden board. Individually the paintings are violent and gruesome, but as a series they create a discomforting orientalist portrait of China. In a sense, the series on corporal punishment, like other series presented, offer a fragmentary glimpse into a commercial (and global) print culture which shaped Western definitions of race in the 19th century. The sheer amount of work presented in a small 2-storey gallery oversaturates viewers within this print culture, inviting us to reflect on the historical, cultural, and economic forces that catalyze and cultivate racist thinking.

The deliberate choice to show a lot in a small space is perhaps also what limits the scope of the exhibition overall. While it is true that the material presented lends itself to questions on the construction of race in relation to capital and trade in the past, “Visualizing Culture” does not actively work to challenge viewers’ own interactions with these concepts in the present. The exhibition does very little to locate the history of these export paintings within ongoing critical discourses of race and colonialism. This imbalance leaves the exhibition in a precarious spot, presenting material ripe for relevant critical interpretations but awkwardly reluctant to engage in that work itself. It may be that this is not the sort of responsibility that an exhibition should take on—after all it is up to us to do that critica work—but nonetheless with the amount of materials on display, “Visualizing Culture” ultimately feels frustratingly incomplete.