Linguistic Vulnerability in Transgression/Cantosphere

Transgression/Cantosphere is the exhibition currently showing at the small, hideaway Centre A Gallery in Chinatown. Commenting on the growing phenomenon of the Mandarinization of both mainland China and consequently Vancouver’s historically Cantonese Chinatown, and spurred on by 2014’s “Occupy Central with Love and Peace” movement based out of Hong Kong, Transgression/Cantosphere is an exhibition attempting to confront political relations between language and space.

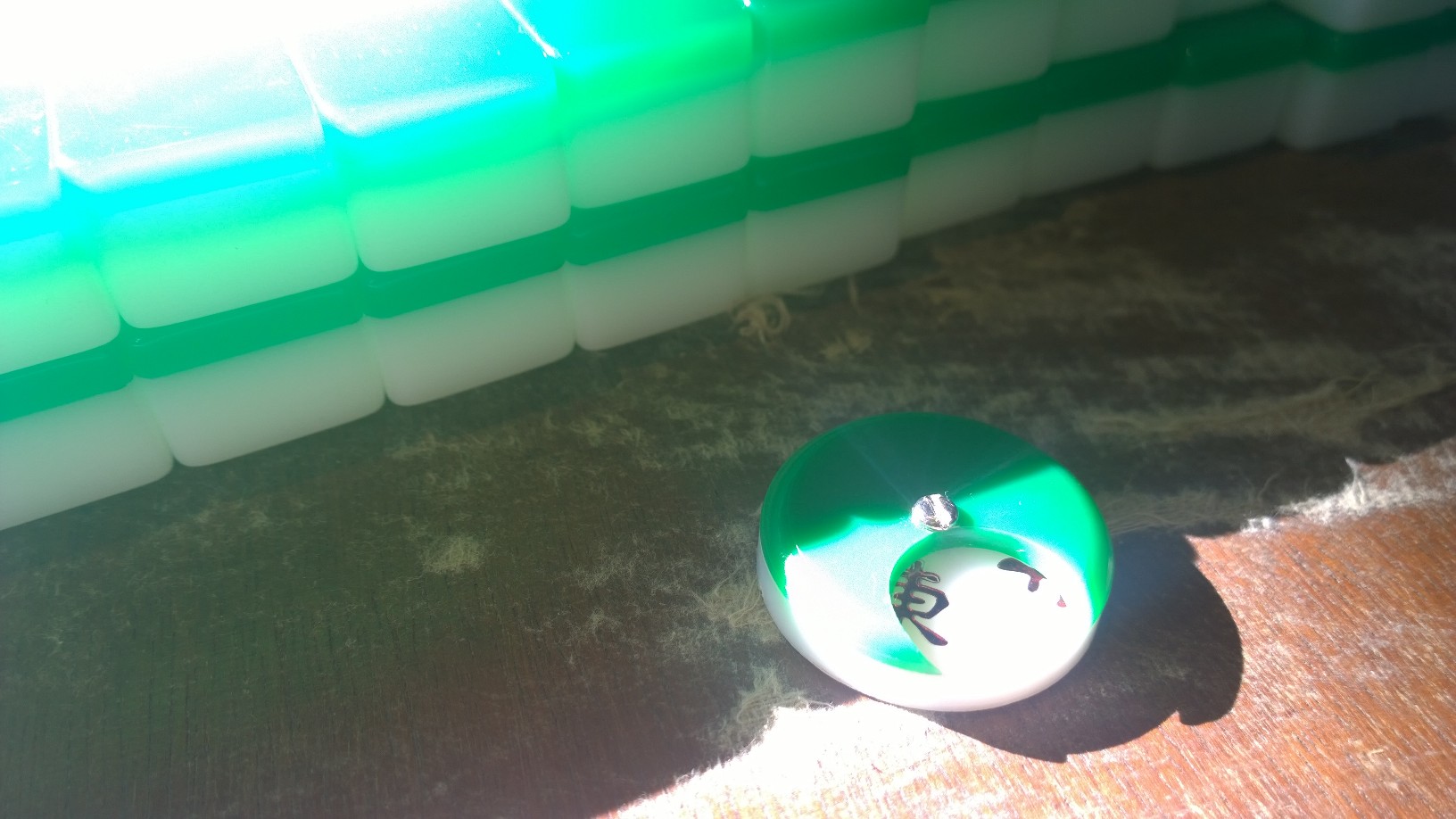

Though Centre A consists of a small single room, the exhibit’s use of its space is noteworthy. A sparse but evocative setup, the show consists of five main elements: a sign proclaiming “Historic Chinatown,” overlaid with projected Chinese characters; a table with a mah jong setup, accompanied by a sound piece audible through headphones; a line of text running across three of the gallery’s walls; a shelf displaying four upmarket, made-in-North-America consumer products; and a video piece involving Cantonese puns narrated by a woman’s voice.

There is a clear endeavour on the artists’ parts to interrogate both language’s imprint on, and susceptibility to, place. Language imprints itself in place over time, and yet the contradiction that Transgression/Cantosphere unpacks is its plasticity, and ultimately its vulnerability. The sound piece played through the head phones around the mah jong table at the front of the gallery records linguist Zoe Lam walking artist Howie Tsui through Cantonese pronunciations. He repeats vowel tones over and over until he gets them right. Lam instructs and encourages, telling him he has a “keen ear”. But these vocalizations are unsure.

The running around the back half of the gallery space is an unbroken string of words taken from the City of Vancouver’s June 2012 Chinatown Neighbourhood Plan & Economic Revitalization Strategy. The end of the word string reads “thisisacriticalmomentintheevolutionofChinatownChinatownneighbourhoodplanandeconomic…” This part of the show stuck out to me because of its subversion of the politically and culturally dominant English language. By decontextualizing these words and melting them into an undifferentiated, run-on line of (what essentially become) letters, its tone of authority is evacuated and its meaning confused. Below, the shelf of western sundries seems to express the encroachment of Western consumer standards into newly coveted real estate space, in spite of that space’s history, community, and language.

The word ‘Chinatown’ is repeated in sequence, the first instance belonging to the statement “the evolution of Chinatown,” the second to the title of the municipal document. This small aspect I found one of the most resonant of the whole show; its paratactic effect jarring the same word in two contexts together: one a (politically fraught) statement of the economic future of a place, the other part of the name of a document infringing itself upon that place’s culture, through impositions upon its economic movements. The language wraps around you, encircling you as you view it; it cages you in. The repetition, being the name of a place, is almost incantatory: “Chinatown, Chinatown…” but is in fact bureaucratic, oppressive. The ‘welcoming’ sign proclaiming “Historic Chinatown” (another, opposite strategy of commodification) is overlaid with Cantonese characters, but they are pale in comparison to the solid, municipal street sign. What Transgression/Cantosphere seems to be calling for is a Cantosphere that retains its power through things as tangible as the official street sign, the municipal document.